The Danish artist’s work explores our bodies as the front line of resistance against a policed state

‘Critical metaphysics’, wrote the French anarchist collective Tiqqun, ‘is in everyone’s guts.’ Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s work starts from the position that our bodies and minds are being shaped by surveillance capitalism, pornographic spectacle and the pharmaceutical industry at the level of our cells, genes and chromosomes. Any coming insurrection against the existing order must, by extension, begin at the level of our nervous systems and bloodstreams. Their work asks what this might look like and, in common with the revolutionary ideology advanced by Tiqqun, whether it could usefully be understood as the ‘accumulation of rage to such a degree that it becomes a viewpoint’.

Working in media as varied as CGI animation, woodcut, sculpture, installation and publishing, the Danish-born, London-based artist critiques the mechanisms of control that conspire to produce docile citizens. In doing so, they address many of the most baffling questions of our time: why do we support economic structures that funnel vast power and wealth to a handful of people? Why do we so eagerly offer up our private information to corporations that we know will sell it to third parties who will then use it to manipulate our behaviour? Why do we continue to work in jobs that make us sick? Why do we subscribe to pharmaceutical products that suppress the symptoms of that sickness to distract from its causes? Why do we continue to live in cities that are, as one of Meineche Hansen’s narrators puts it, “machines to collect personal data about its residents”? Why, to paraphrase Rousseau, do we run towards our chains?

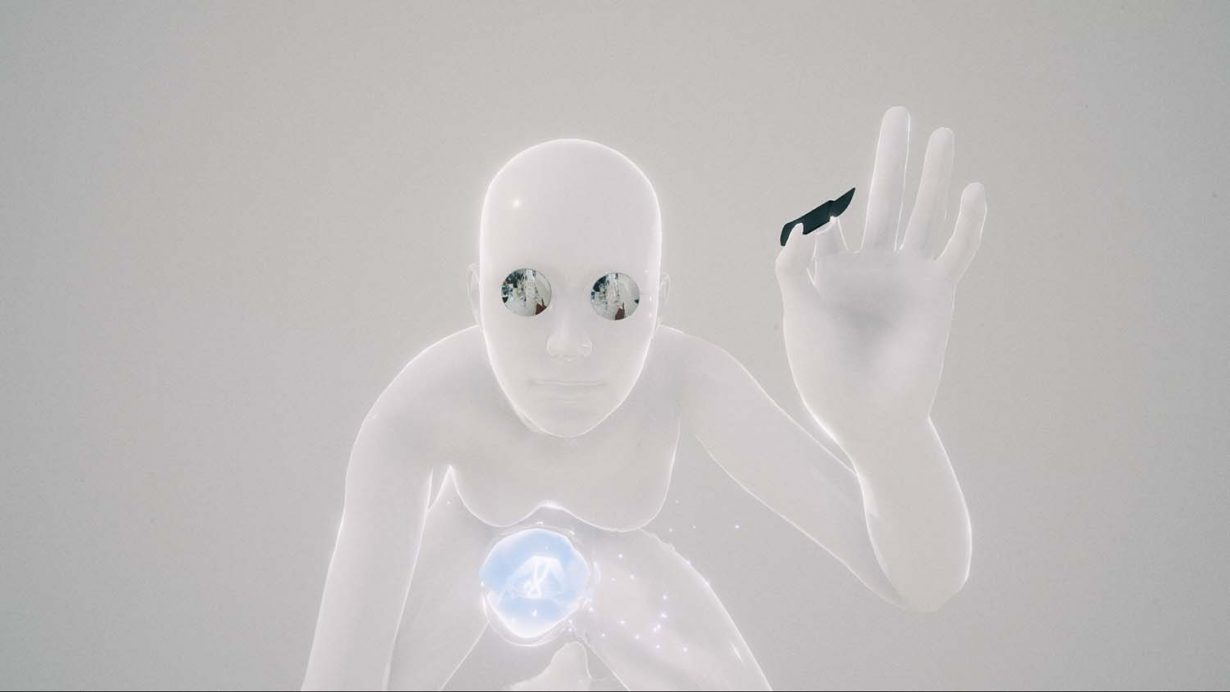

These preoccupations are introduced in the CGI animation Seroquel® (2014), first exhibited at London’s Cubitt Gallery. The eight-minute work is named after an antipsychotic drug that became notorious after its manufacturer – the now household-name AstraZeneca – was fined half a billion dollars for paying kickbacks to doctors who prescribed it to patients (including children, the elderly and prisoners) to alleviate conditions for which it had not only not been approved but that were as diffuse as aggression, anger management, anxiety, depression, mood disorder and sleeplessness. Promotional material for a pharmaceutical company showing the passage of its product through the body is spliced with scenes in which a female avatar experiences what is either a catastrophic breakdown (paradoxically, the listed side-effects of Seroquel include psychotic symptoms) or a liberating transformation. In the context of work that foregrounds body hacking and physical metamorphosis as a means of escape, it might conceivably be both.

A voiceover read by the iconic New York singer and writer Lydia Lunch – based loosely on a conversation between anthropologist Gregory Bateson and his daughter Nora – discusses the means by which capitalist society “produces” citizens to fit cybernetic systems that are superficially dynamic yet always tend towards equilibrium and control. The dialogue describes a historic development in the operations of power that is at the heart of Meineche Hansen’s work: it’s a development that moves from the “disciplinary control” of legal and political frameworks, through the “biopower” by which states intervene in the health of their citizens in order to maximise the efficiency of their labour force, to a present in which the tech, pharmacological and pornographic industries mould our sense of self to their own ends. The law becomes less necessary as an instrument of coercion when we are physically and psychologically conditioned to behave in ways conducive to the status quo. This, the voiceover tells us, is “the industrial complex of your emotions”.

The entanglement of drugs and pornography is embodied in Seroquel® by EVA v.3.0, a free-to-use stock 3D-model designed for deployment in CGI pornography who goes on to star in several of Meineche Hansen’s animations. Her transition into the art industry recalls Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe’s purchase of the manga character AnnLee from a Japanese animation studio, with the difference that while the two male artists felt comfortable in stating that they were ‘liberating’ their conspicuously female muse, Meineche Hansen makes no such claims. Indeed, a woodcut reproducing the ‘morph function’ of EVA v.3.0’s genitals as detailed in her user manual (HIS CORPORATE CUNT ART, credit Nikola Dechev, 2016) takes pains to credit her creator in the title. As elsewhere in Meineche Hansen’s oeuvre, what seems like an unambivalent expression of righteous anger is more conflicted than it first appears: this act of naming is both a calling out of institutionalised misogyny and an ethical acknowledgement of the creative labour hidden behind open-source software.

Rather than play out some imagined freedom, EVA v.3.0 tests the limits that constrain socialised individuals, and specifically women: in the VR work NO RIGHT WAY 2 CUM (2015), for instance, she masturbates and squirts onto the camera in defiance of the British Board of Film Classification’s injunction against female ejaculation. When it was exhibited at London’s Gasworks, the work not only highlighted a state proscription on the representation of female desire but raised the question of whether avatars are subject to the same regulations as the women they replace in the production of pornography.

This contested boundary between supposedly free subjects and manufactured objects was further explored in the 2018 documentary short Maintenancer, made in collaboration with Therese Henningsen. We are introduced to the madam of a German brothel, Evelyn Schwarz, who tells us about the increasing popularity of silicone sex dolls and their advantages as employees: they are never late, always presentable, don’t get sick, and so on. These dolls seem initially to represent the apotheosis of late-capitalist economic relations: perfectly frictionless and transactional exchanges, unhindered by unreliable bodies. Yet “aesthetic perfection”, Meineche Hansen writes to me, “I associate with an erasure of the labour that goes into capitalist production”, and soon Fräulein Schwarz is reminding the viewer that these dolls are supported by a “different kind of work”.

This is the labour of the titular ‘maintenancer’, the woman who cleans the dolls in between sessions and performs various other forms of care. We see her disinfect a blonde named Anna’s orifices before tenderly repainting her nipples and vulva; we learn that she worked previously as a trained assistant in a care home. As she makes a cup of tea to calm the nerves of a client, we learn that the men often thank her for having ‘taken some of the anxiety away’ from their encounters. Nervousness, anxiety and anger are figured in Meineche Hansen’s work as natural physical responses to the social pressures of twenty-first-century life, and here we catch a brief glimpse of one way in which those feelings relate to an escalating crisis in masculinity.

While her labour is made visible by the film, the face of the ‘maintenancer’ is never shown, her name not given. This expresses another of the tensions that animate Meineche Hansen’s work: when so much capitalist exploitation is predicated on hiding the labour that underpins its production, there is a moral imperative to draw attention to those workers; yet to profit from the publication of an individual’s identity is to exploit them. Particularly in a surveillance society.

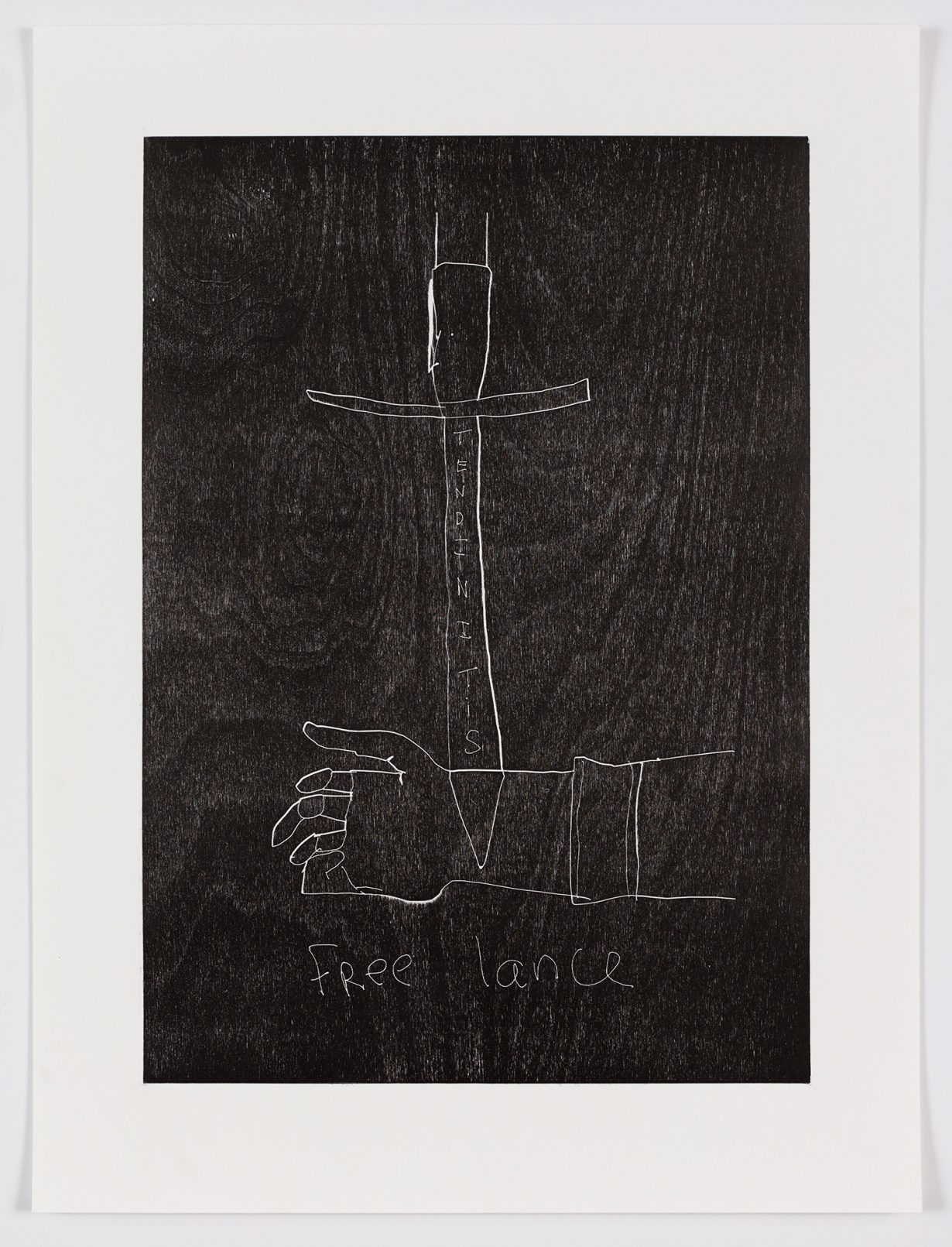

The emergence of ‘the artist’ in the West offers a useful historical model for this dialectic. A shift that began when workers started signing objects to secure recognition for their labour has led inexorably to a situation in which the object is subordinate to the individual’s ability to manufacture and sell themselves. Meineche Hansen’s Manual Labour series of expressionist woodcuts (including Tendinitis Freelance, 2013) dramatises the sense that, these days, the late-twentieth-century utopian mantra that everyone is an artist might have been realised in a society where everyone now sells themselves (and far too cheaply at that).

This central issue of consent finds diverse expressions in Meineche Hansen’s work, ranging from a short animation in which an extrav- agantly endowed EVA v.3.0 fucks an amorphous biomorphic blob named iSlave (when I saw the work at Rodeo in Piraeus, the screen was suspended from a makeshift wooden BDSM structure) to the video installation End-Used City (2019). First exhibited at the Chisenhale Gallery, End-Used City is set in a dystopian near-future London that very closely resembles the present. Using an Xbox controller, the viewer gains access to the city by interacting with a monstrous animated figure (their body a patchwork of the faces of tech billionaires). But the promise of choice is largely illusory: the viewer is simply led to three short videos in which a young woman moves through the city, her interior monologue delivered in the lilting Scottish accent of a programmable sex-robot named Harmony.

Over the course of the three instalments, this flaneuse reveals herself to be an agent harvesting data on behalf of the overseeing Leviathan, whose composite body alludes to the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s notoriously misanthropic 1651 treatise. According to Hobbes – for whom human life is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ and tends naturally to a state of ‘war of all against all’ – the only way to maintain order is through absolute power legitimised by a social contract between autocrat and citizens. This contract is implicit: by being born into a state you give it authorisation to withdraw your liberty if you break the terms to which you automatically signed up (by disrespecting private property, for example). This template for contemporary capitalism has obvious parallels with the operations of power online, in which we unconsciously sign away our freedoms by clicking cursorily through the various ‘end-user’ contracts that grant access to the internet’s resources.

Hobbes’s low opinion of citizens meant he believed that they could be corralled into a society only by incorporation into a body politic that concentrates power at its summit. This ‘problem of the head’ was theatricalised at the Chisenhale by the presence on the floor near to the video installation of a decapitated and pointedly male head in clay (HIS HEAD, 2014). If this sculpture suggests that in principle the problem is easily solved, then Meineche Hansen’s work also pursues some more practical strategies by which to resist our co-option into exploitative systems. In An Artist’s Guide to Stop Being an Artist (2019), a video monologue observed with professional interest by a ball-jointed, sex-toy-compatible wooden figure lying on the ground of Copenhagen’s SMK gallery, Meineche Hansen recommends tactics including being “difficult to work with”. The advice to aspiring artists might be laced with typically dark humour, but it also draws on the history of micropolitical industrial action – slow-working, tardiness, illness – pursued by disenfranchised subjects with no other recourse.

The predicament in which both critical artists and critical citizens find themselves is that to withdraw from the system is to be defeated by it. “I don’t think you can mentally avoid the double bind,” Meineche Hansen tells me, “because it’s part of how capitalism operates and how colonial logic is structured.” The alternative is that by “working through the double bind in ways that are analytical and material” it might be possible to raise awareness of those internal contradictions in the hope, perhaps, that they might eventually tear the system apart. The function of the artist is not, according to this reasoning, to perform a romantic illusion of freedom – comforting because it allows the viewer to believe that liberty is still possible – but instead to draw attention to irreconcilable conflicts within a system that constrains the viewer. The practice of freedom cannot be outsourced to artists, or activists, or anyone else. It is work we have to do ourselves.

Currently on display at Rodeo in Piraeus, the burned wooden sculpture ONE-self (2015) depicts a totemic figure that is part pornographic priestess and part snake-headed god. We are all chimeras, it suggests, our conflicted selves constructed by spectacle and pharmacology (the snake nods to the serpent twined around Asclepius’s rod). Meineche Hansen’s deeply ambivalent work suggests that if the insurrection is coming it will take the form of a civil war: less a pitched battle between two teams of sovereign individuals fighting on the streets under the banners of Us and Them, more a long conflict within the self to regain control of our own bodies and minds.

To answer the question of what that might look like, Meineche Hansen’s work insists that we take a look around. When populaces are controlled through the body, civil disobedience might take the form of that dismantlement of gender binaries and ‘body hacking’ that theorists including Paul B. Preciado have advocated. But not all revolutions are theorised or even conscious, and we might equally cite the startling recent proliferation across society of those embodied and rebellious feelings – depression, anger, psychosis, exhaustion – that are threatening to make the capitalist West unmanageable. In which case, Meineche Hansen’s work suggests, it might be that the revolution has already begun.

Work by Sidsel Meineche Hansen is on view in ανάβασις*, Rodeo Piraeus, through 26 March, in *standstill, Rodeo London, through 2 April, and will be included in The Milk of Dreams, the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 23 April – 27 November.

ALIEN BABY 0 Rules for life, a vinyl record of music by Joanne Robertson and Sidsel Meineche Hansen, was released in February