Edward George’s audio-visual musing on the representation of Black figures in Western art is at once immersive and incantatory

Sometime in the 1960s, Dominique and John de Menil, the founders of the Menil Collection, began assembling an archive of images depicting Black figures in Western art, spanning antiquity to the mid-twentieth century. This body of material later became known as The Image of the Black Archive. Speaking to ArtReview, Dr. Matthew Harle, curator of artistic programmes at London’s Warburg Institute, explained that the Menils intended the library to serve as a Civil Rights era resource for African Americans to “see themselves or witness their own representation in art”. Yet, when poet, essayist and filmmaker Edward George encountered it, he found ‘‘very little Black presence at all’’.

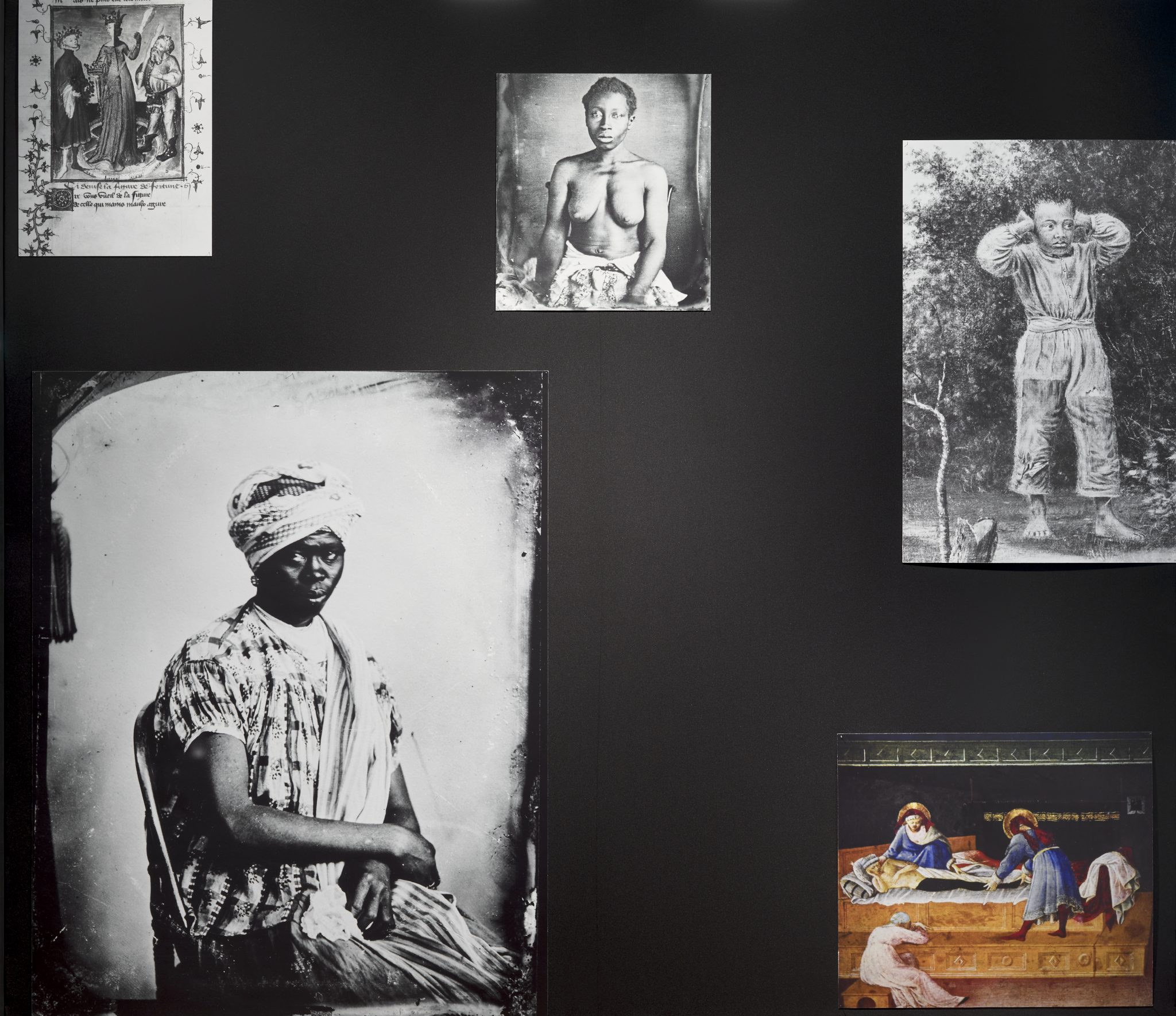

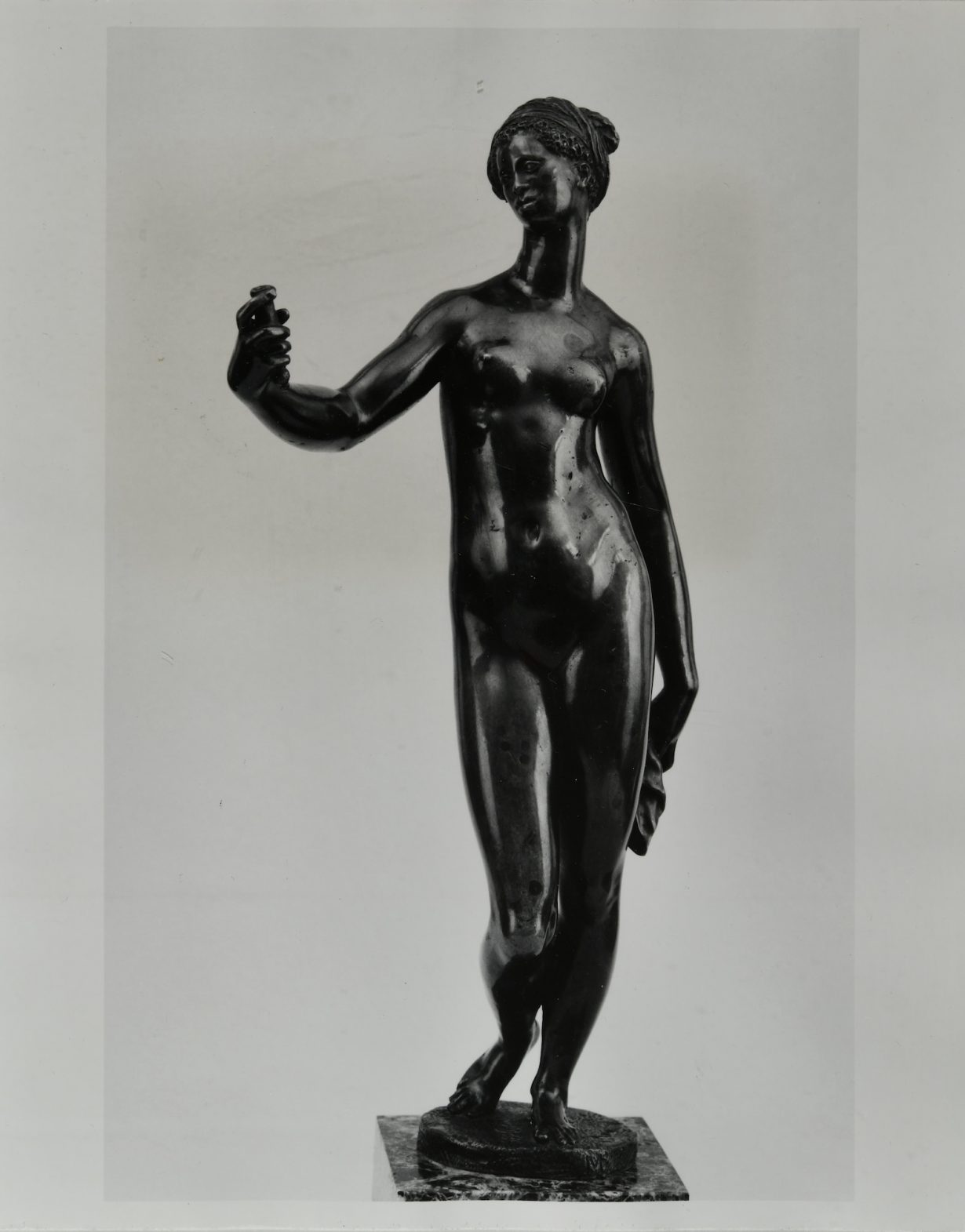

Now, George has reimagined the Menil’s archive to create Black Atlas, an audio-visual work presented in conjunction with a separate display of collaged panels at the Warburg. George – a member of the seminal Black Audio Film Collective, known for its melancholic 1980s and 90s films on imperial legacies – spent twelve months reviewing the Menils’ archive’s 30,000 images to produce the work. It takes Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – a set of panels of collaged images linking antiquity to modernity – as a starting point, adopting the art historian’s associative, image-based methods of analysis.

Black Atlas is structured in nine conceptual sections based on recurring themes, each forming part of a 57-minute loop. Fragments of the archive are projected onto double-sided black panels in three bays. George’s commentary, patient and wizened, guides us along, soundtracked by a slow, improvised jazz suite with instruments drifting in and out: low violin, muted strings, a dull, vamping horn. Beneath it hums the static whirr of an electric device and a light, irregular drumming that fades and returns.

The images in Black Atlas exploit the ambiguity of what the viewer sees, connects and interprets, an ambiguity that mirrors and reinforces the film’s associative, non-linear logic. Each section is anchored by a philosophical and historical framework exploring embodiment, recognition and trauma, drawing on key texts and starry names such as Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan and W.E.B. Du Bois. George’s sensorial medium – menacing music, mostly monochrome images, and inimitable baritone – is almost inseparable from the work’s intellectual rigour. The layering, meanwhile, creates an emotional architecture reminiscent of Charles Mingus’s 1963 jazz ballet, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, for its core tension between restlessness and restraint.

The denigrating depictions of Black people in the film and gallery represent only a fraction of the Menil survey: 400 out of 30,000 images, to be precise. In George’s hands the synthesis is seamless, swirling, ruminative and incantatory. It is deeply unsettling and routinely upsetting. Crucially, George does not generate distaste out of distaste – any base-level discomfort is processed through his analytical and theoretical discursions. One particularly striking example is of a miniature Black figure, possibly a child, turned into the decorative armrest of a lounge chair. Carved directly into the wood, the figure is placed beneath the armrest of a piece designed purely for comfort. The image is profoundly unsettling, sickening even, yet George does not dwell on shock or outrage.

George’s combined editorial range, image selection, sonorous delivery and syncretic text is certainly immersive. Central to his narrative gambit is his inhabitation of a remarkable array of historical figures: Herodotus, Atticus, Toussaint Louverture, Memon, William Freeman and an enslaved African American man, Renty Taylor, with his daughter Delia. In merging the experiences of the elite and the enslaved into a single voice, he elicits empathy and collapses temporal and social boundaries, creating a narrative that is both expansive and intimate. George identifies as Renty Taylor while the image of an African American man appears: ‘Who am I? You sir, are Renty Taylor, an enslaved African. You were born around 1775.’ Gaunt, grey, emaciated, bare-chested and with aposematic eyes staring squarely into the camera, he is clearly a man who has endured untold suffering. The images of Renty and his daughter Delia were commissioned in 1850 by Louis Agassiz, Harvard’s Swiss-American naturalist and proponent of the racist ‘polygenesis’ theory, who sought to prove Black people were a separate, inferior species. Tamara Lanier, claiming descent from Renty, sued Harvard for ownership in 2019. The court ruled in Harvard’s favour: since Agassiz commissioned the images, he owned them.

Even in death, over a century later, Renty’s image and spirit remain embroiled in legal disputes, scholarly circulation and ethnographic discourse. As Saidiya Hartman observes in Scenes of Subjection (1997), slavery persists in Black America because ‘black lives are still imperilled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago.’ Hartman frames slavery’s legacy as active and unceasing: a reality George’s prose poem acknowledges with dry, fatalistic humour: ‘Scholarship is when you are fighting armies of ghosts as if they were alive, and when you look at the living as if they were ghosts.’

While the Warburg Institute has long preserved its archive, this exhibition marks a rare instance of inviting a contemporary artist to respond directly. George’s year-long residency and engagement with the materials represents only the beginning of a reckoning: it acknowledges the archive’s historical imbalances without attempting to redress the profound harms embedded in its creation. The exhibition’s uncompromising design, its black-and-white imagery and methodical layering of death and leisure – the necropolitical order of Western societies – culminates in a stratified mountain that enacts a dialogue between memory, power and ethical reckoning. The camera zooms in to view a skeleton in a rectangular coffin, standing vertical. It then pulls back to reveal other coffins on that layer, then additional stratifications, horizontal lines cutting across the mountain landscape. Above ground, Black figures labour whilst white supervisors observe and white women idle. Below, the dead are carefully arranged. The mountain diagrams racial capitalism’s foundation as Black death, literally.

Crucially, no Black person made this image either. Like almost all 30,000 in the archive, it channels white European and American projections, a collection formed through their visual imagination alone. George’s contribution is diagnostic, not redemptive. In the end, George concedes to the unknowable: ‘Maybe the thing to listen and look out for… isn’t so much what the voices of the dead tell us, but what their voices could not in life recall.’ Much like Black Atlas, it is a prospect at once frightening and inspiring.

Edward George: Black Atlas is at The Warburg Institute, London, through 17 January 2026

Read next It’s Art Historian Aby Warburg’s World. We’re Just Living In It