The limits and liberations of the German scholar’s celebrated atlas of images

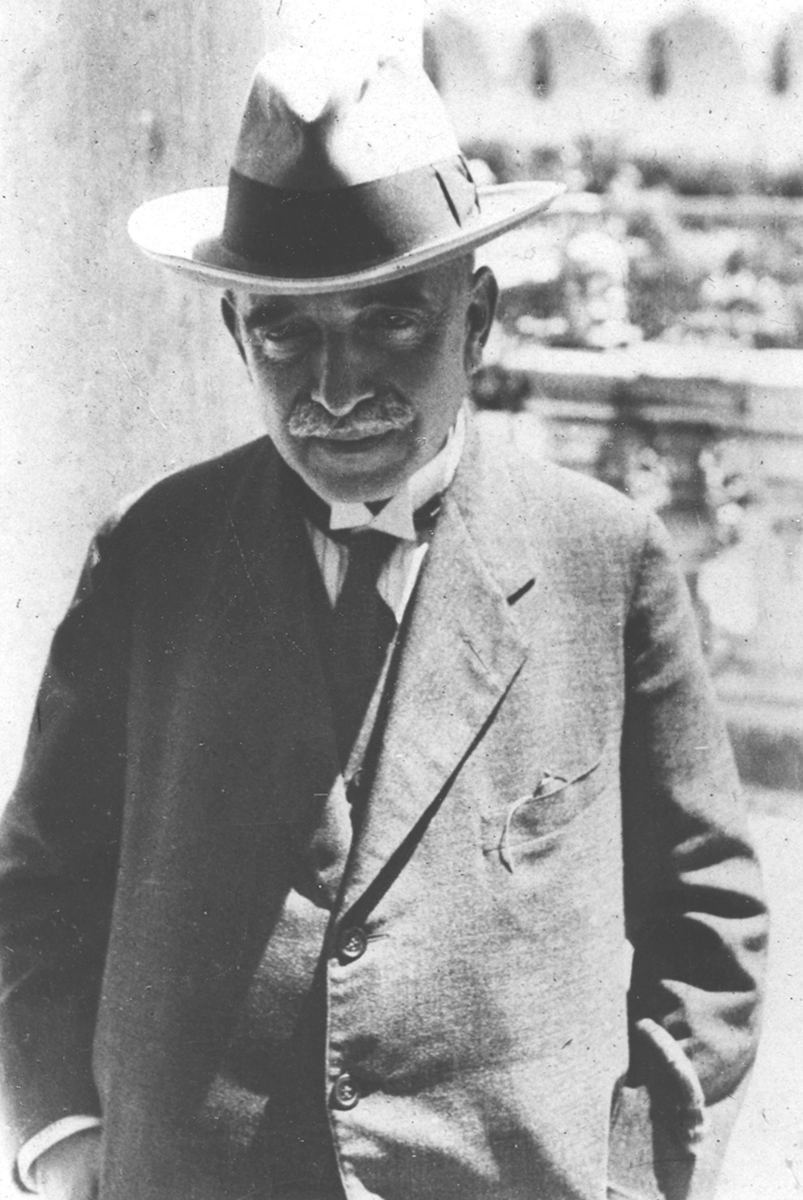

Photo: Wootton/fluid. Courtesy The Warburg Institute, London

Your first impression on encountering this reconstruction of German art-historian Aby Warburg’s most celebrated work is that it looks like a primitive, pinboard version of a Google image search. Or the evidence board in some 1970s crime movie. Yet to many, Warburg’s Bilderatlas (picture atlas), begun in the final years of his life and incomplete at his death, in 1929, represents the origins of modern (Western) art history, when disciplines such as iconography, sociology, ethnography and psychology were introduced into a history of Western art that had until then been dominated by aesthetics alone; to others it presages contemporary image-culture; while to others still it really is symptomatic of Warburg’s ‘crimes’. For Warburg himself it was part of ‘a laboratory of the study of civilization’. As long as you accept, according to a map that opens the presentation, that civilisation is the property of a geography that stretches from Bagdad to Coruña and from Hamburg to Aswan. Prepared according to Warburg’s instructions, it’s titled ‘The Road Map to Cultural Exchange Routes’.

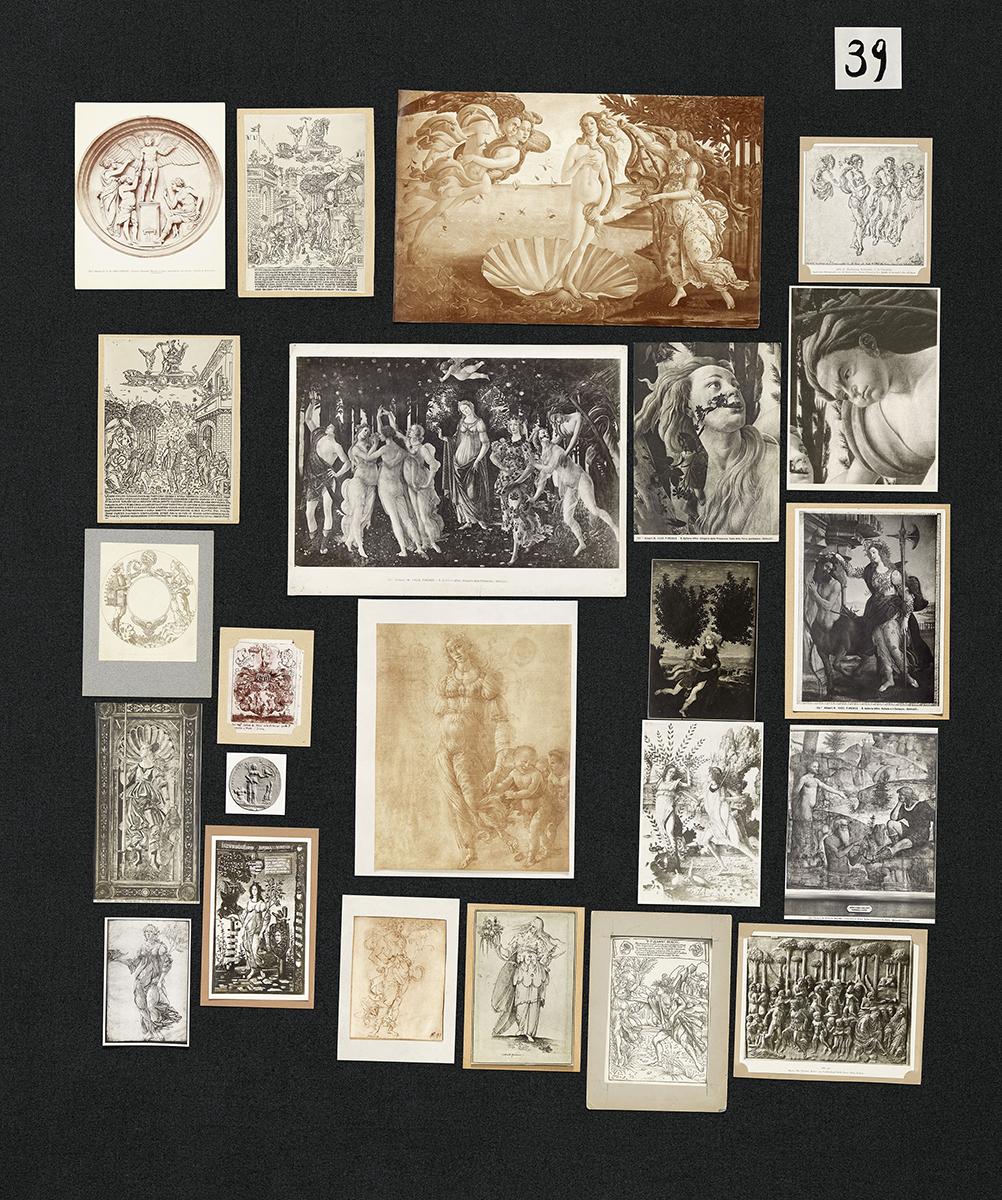

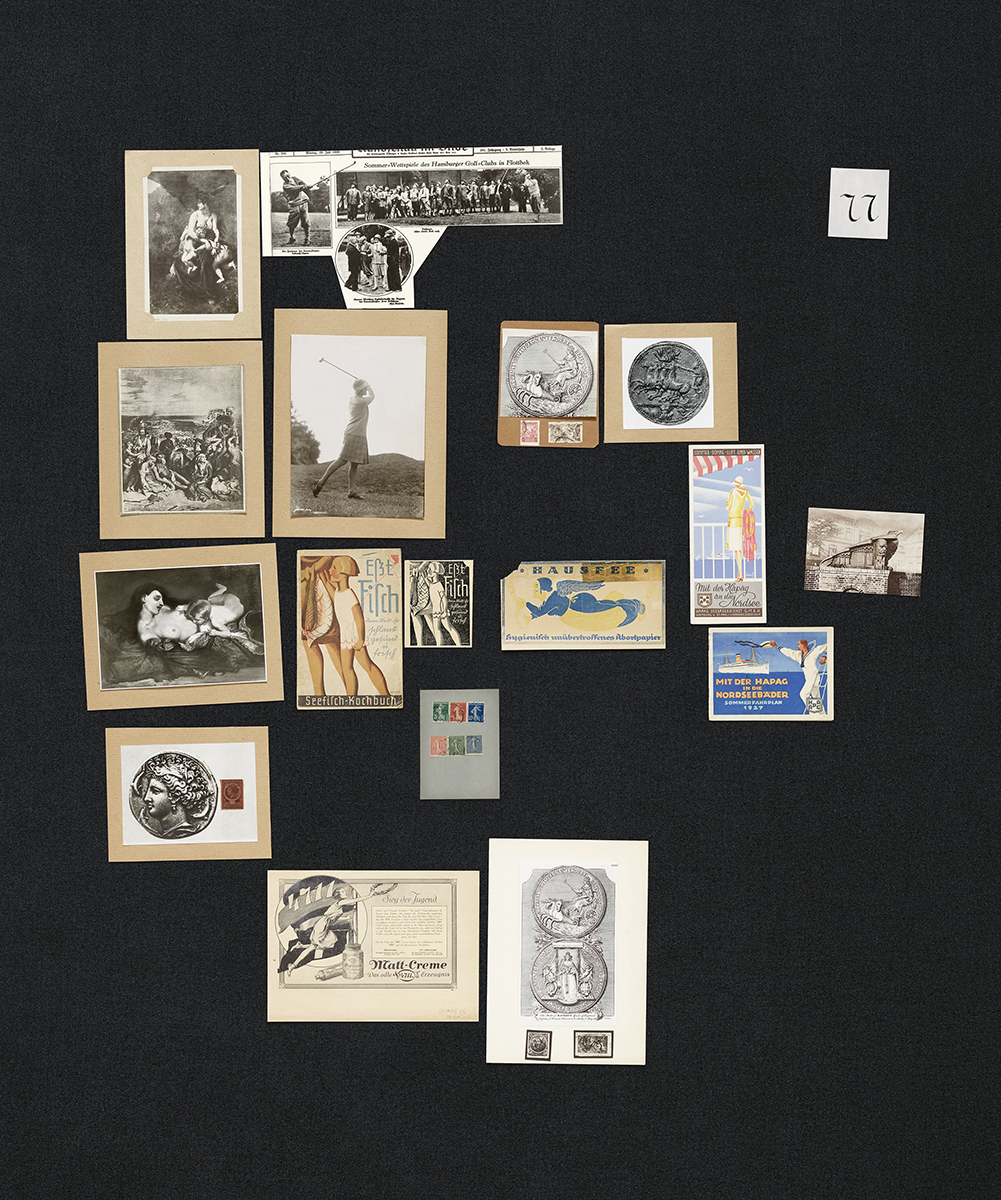

The Bilderatlas comprises a series of 63 panels with black-felt backgrounds that collectively feature 971 images comprising photographic reproductions of artworks stretching from Antiquity to the Renaissance, mixed in with newspaper cuttings and advertisements, stamps, images of coins and astrological charts. Warburg had begun the project of assembling his visual archive in 1924, tracking its references, evolutions and recombinations using a card index as he moved his vast undertaking towards a planned book form. A version of the project, of which this exhibition (also available for online study) is a meticulous reconstruction, was exhibited in 1929, not long before Warburg, an independent scholar and scion of a wealthy banking family, died. The planned three-volume book unrealised.

Photo: Silke Briel. Courtesy Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

The panels are arranged so as to suggest connections and leaps across time and space, and to argue for the fundamental importance of the visual within more general studies of culture. Panel 72, for example, features representations of drawings and paintings (largely Christian or Classical) featuring dining, plotting and other more or less sinister forms of conviviality alongside photographs of contemporary religious ceremonies and student dinners. Panel 77 features history paintings by Eugène Delacroix, representations of various nineteenth-century monarchs surrounded by iconography of the sea (Queen Victoria in her shell carriage), a series of stamps from France featuring Liberty sowing the seeds of freedom at sunrise, a pre-Christian coin from Syracuse and a photograph of a German golf champion caught mid-swing.

Photo: Wootton/fluid. Courtesy The Warburg Institute, London

Through the course of this exhibition, as the panels flip between an at times seemingly rational and at other times purely empathetic logic, you’re not sure whether Warburg’s great project is saying that something changed as civilisations travelled through time and space or that nothing really changed – that culture is no more than the product of a fixed but mutating iconography: appropriation followed by reappropriation; a series of eternal returns (Warburg was influenced by the work of Friedrich Nietzsche).

It’s the kind of exercise that was still in place if, like me, you studied art history (at an institution in London associated with the one that bears Warburg’s name) during the 1990s, and informs the work of artists ranging from Marcel Duchamp to Gerhard Richter (whose own Atlas collects together photographs, sketches and newspaper cuttings that the artist has collected since the 1960s), and is more currently linked by some critics to the work of Hito Steyerl and even the montage techniques of American artist Arthur Jafa. A series of panels (39 and 41) highlighting facial expressions and body gestures suggest that Warburg might have had more than a passing interest in emojis too. You can see more sinister parallels in Trevor Paglen’s recent explorations of how AI networks are taught to ‘see’, or in Liu Chuang’s exploration of the evolving iconography of power and resistance in the three-channel video Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018).

But Warburg wasn’t interested in China, and looked to the past more than the future. He looked to visual imagery as holding the unconscious memory of civilisation’s uncivilised pagan past (hence the reference to Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory, in the Atlas’s full title), a world in which there were humans and nature, and the one interacted with the other. One of the three introductory panels setting out the methodology of the project features a fifteenth-century diagram of the body as it is affected by the animal signs of the zodiac, Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1487) and a sixteenth-century division of the hand according to the planets, each suggesting intriguing, yet unexplored, relations with Tantric art and Ayurvedic medicinal illustrations. Warburg wasn’t interested in that either.

He was interested in the Native American Hopi people whom he visited following his marriage in 1895, documenting their serpent dances before going on in subsequent lectures to suggest that they had connections to religious thinking in ancient Athens. Because civilisation, as we know, is European, transmitted from the lands of the Bible. By contemporary standards his map looks small and selective, tracing a story that goes from Antiquity to Judeo-Christian tradition with the Renaissance as the melting pot of the two. But back in the 1920s there were no satellites, no cheap air travels, no TikTok, and maps were full of willed and unwilled blank spots.

Photo: Silke Briel. Courtesy Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

Warburg’s photographs of the Hopi rituals are not part of the Bilderatlas (their posthumous publication, to illustrate Warburg’s lectures, has led to conflict with the Hopi, who are demanding the restitution of their cultural artefacts and whose traditions do not allow information about their rituals to be passed to the uninitiated), but, alongside what may today be seen as various instances of cultural appropriation, an interest in the serpentine runs through the atlas. The panels are arranged in curves as if to suggest some sort of ouroboros, and Warburg himself, like the eighteenth-century German philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing before him, was, on the evidence of the panels here, fixated on the image of Laocoön, a mythical Trojan priest who, along with his two sons, was devoured by serpents sent to execute him by the gods. For Lessing, ancient sculptures of Laocoön provided an excuse to meditate on the limits of visual art and poetry, and Warburg is doing something of the same. The 59-page brochure

of captions that accompanies this exhibition, simple descriptions that range from ‘boat with musician’ to ‘Gaudenzio Ferrari, Christ Before Pilate, 1953’, seems expressly designed to emphasise the fact that words are never enough.

In a present in which everyone complains about the overwhelming saturation of image culture, and moans about having to navigate

a world full of half-truths, alternative truths and plain untruths, the Bilderatlas, despite its idiosyncrasies, its evident flaws and blindspots, remains an intriguing example of one man’s attempt to create some sort of coherent world-view at a time when the world, interwar and on the point of economic collapse, seemed disparate and fractured. Which can be both a dangerous and a liberating thing. The true world, after all, is often rather less coherent and far less obedient than we would like it to be.

Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – The Original was on view at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 4 September – 1 November 2020