Amelia Roberts examines the culmination of a year-long residency at ArtCore Gallery in Derby, which deconstructs punishment, obedience and the limitations of human and artificial intelligence

Error & Power is an exhibition by Naho Matsuda and Neale Willis that questions the failures of systems of power and learning, and consists of works completed by the artists during Artcore’s online residency programme.

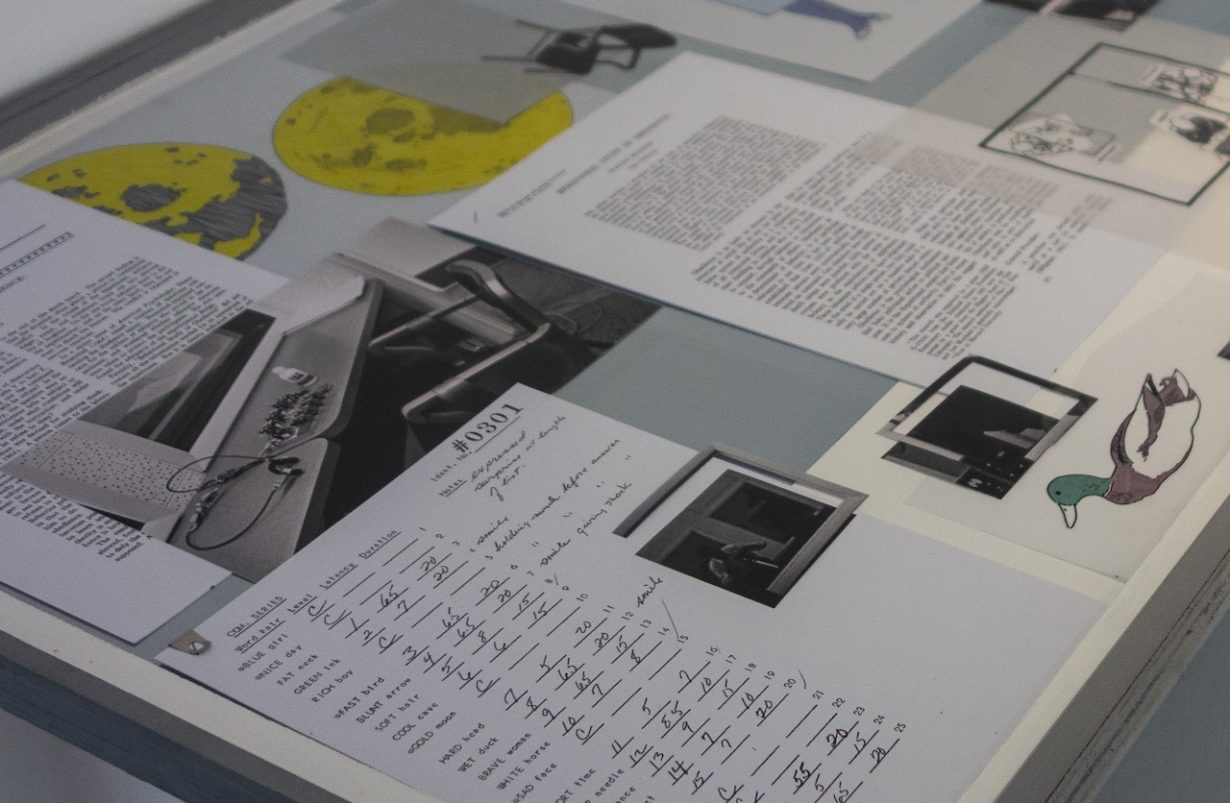

In the infamous ‘Milgram experiments’ of 1961, ostensibly devised by Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram to examine the effect of punishment as motivation for learning, each volunteer was designated as a ‘teacher’, instructed to administer increasingly painful electric shocks to their ‘learner’ counterparts, as punishment for misremembered word pairs. In truth, however, the ‘learners’ were actors and their errors had been scripted. Naho Matsuda chooses this collection of simple adjectives and nouns as the focus of her three-channel videowork Please Continue (2020). As the righthand screen flashes these written combinations consecutively, the central screen presents a portrait of the artist reading the word pairs aloud. On the left, a catalogue of images is shown in sync with these declarations; each image an illustration of possible meanings created by each pair, leaving ample room for interpretation. Markedly, punishment and violence are absent.

A seemingly irrelevant aspect of the Milgram experiments, the word pairs were a tool to distract from the real purpose of the study: to measure the obedience of ordinary men in committing acts of violence at the request of authority. Psychologists at the time predicted that perhaps two or three percent would follow instructions to commit dangerous harm; the alarming reality was that two thirds were prepared to deliver a potentially lethal shock to the learner. Matsudo’s video is devoid of the terror and trepidation of this notorious experiment, presenting instead a network of language and visual interpretations akin to a memory aid or tool for conditioning.

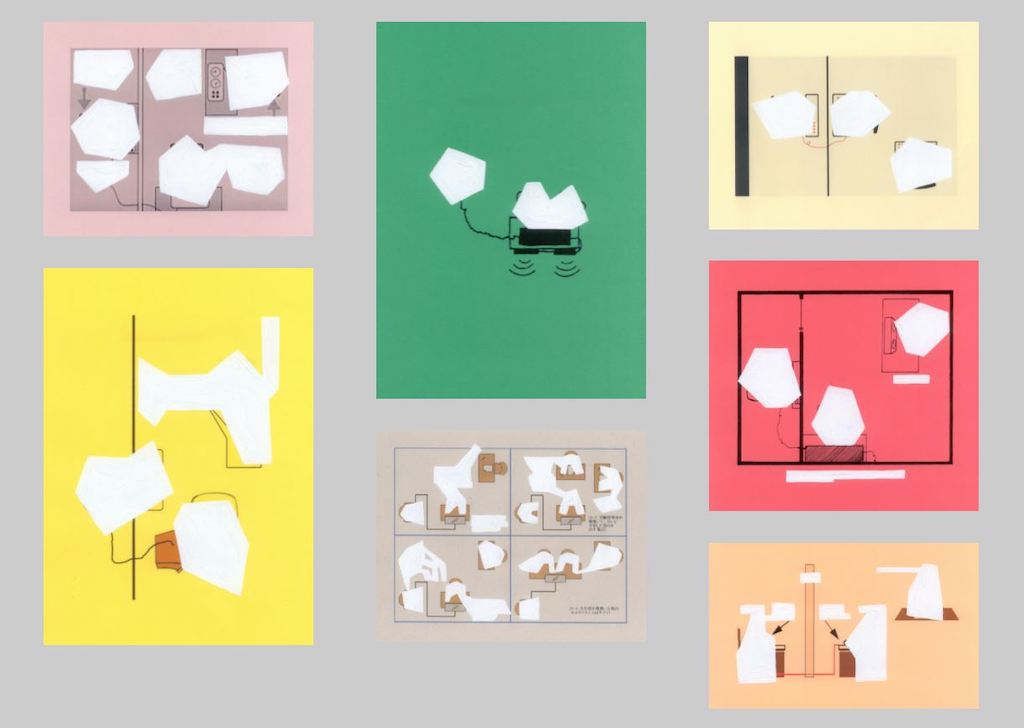

Blue Girl, the title of this group of Matsudo’s works, establishes links between language, violence and authority also shown in previous works by the artist. In Firm, but not impolite (2020) a series of instructional blueprints of the physical layout of the experiment have been redacted using correcting fluid, the human figures and instructional texts in each drawing obscured. Echoing the learner’s intentional errors and omissions, this erasure, and the anonymity it produces, implies that the personal ethics of each participant are necessarily repressed in the pursuit of following orders.

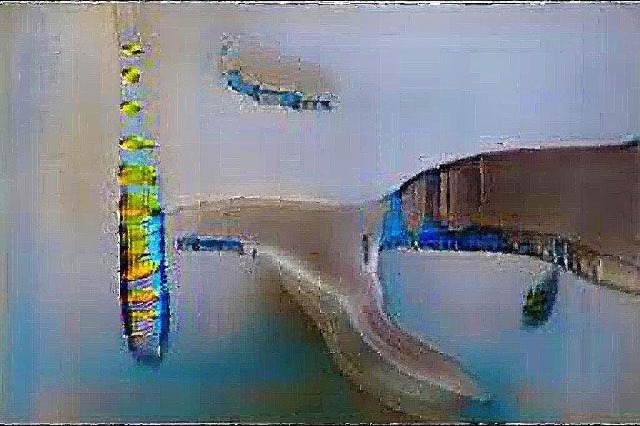

Neale Willis’s explorations of ’error and power’ exemplify the limitations and blunders of AI-human artistic collaboration, by making the computer represent its understanding of the intimate space of a domestic bathroom. Following the artist’s orders, the AI trawled through the Zoopla property website, amassing a vast collection of bathroom photography it would use to construct its own dream-like amalgams of bathrooms. The search produced a predictably inaccurate selection, requiring the artist’s corrective labour to achieve satisfactory results. The machine is given permission to dream, but only within the constraints set by the artist.

Dystopian science fiction writers, scientists and philosophers share anxieties regarding the escalating trajectory of AI. Elon Musk has expressed his concern that AI constitutes an existential threat to humankind, despite hosting an AI Day at Tesla in late August. Willis appears to question the creative capacities of AI, and his work sits in the lineage of the Philip K. Dick’s sci-fi novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). But Willis appears not to share Dick’s concerns, who positioned AI as a ‘mirror’ to a culture drained of humanity. Instead, Willis highlights the errors generated by the programme when trying to understand beyond the pixels. That said, the artist’s deliberate use of outdated AI overlooks newer unexpectedly inventive or accurate AI, such as the psychedelic, puppy-eyed aberrations of Google’s ‘DeepDream’ or the unsupervised pattern recognition of Facebook’s ‘SEER’.

The success of the work depends less on the discrepancies and misunderstandings of the algorithm and instead nurtures an empathetic approach to the labour exchanged between the artist and the computer, AI as both a medium and dependent learner.

The works in Error & Power echo sentiments which emerged in the 1960s, but which clearly still relate to current ethical and technological questions regarding authority and knowledge in an information age. Although, as scientific understandings of sanctioned violent behaviour and increasingly intelligent artificial neural networks are developed, it is important that artists seek to move beyond illustrating such concepts and look to affirm new positions on the subject; unless perhaps, we have already been surpassed by a generation of creative AIs, much better equipped to do so.

Error & Power is at Artcore, Derby, until 4 September

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here