Exteriors – Annie Ernaux & Photography at Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris asks which comes closer to presenting reality, text or image?

In her 1996 book of journal entries, Exteriors (first published in French as Journal du dehors and translated into English by Tanya Leslie), Annie Ernaux asserts her intention to ‘preserve the mystery and opacity of the lives I encountered’, aiming in her writing to ‘describe reality as through the eyes of a photographer’.

How might a photograph be read, or a book seen? Between a text or an image, which comes closer to presenting reality? These are the central questions of Exteriors – Annie Ernaux & Photography, an exhibition that recently opened at Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris. In it, excerpts from Exteriors sit by side with more than 150 photographs from the MEP collection by 29 photographers, including major names such as Harry Callahan, Claude Dityvon, Issei Suda and Dolorès Marat. While Ernaux’s observations are distinctly situated in a French context, the photographs, many of which are of everyday domestic and street scenes, include pictures taken the UK, the US and Japan as well as in France. Like Ernaux’s clean, no-frills writing, the several small rooms are sparse. Clusters of photographs hang alongside extracts from the text with plenty of white wall space in between. Ernaux’s writing does not describe the images; the images do not depict exactly what Ernaux describes. Rather, the viewer is required to insert themselves into the space in order to join the dots, or work out whether they see a connection between the two at all. The resulting experience feels like an intimate conversation.

Born in Normandy in 1940, Ernaux is now a world-renowned and Nobel Prize-winning writer for her autobiographical works on sex, abortion, love and death. Her writing is crisp and precise; for many of her avid readers – particularly young women working out how to resist a world of patriarchal norms and gendered expectations – it is revelatory.

Ernaux has also written several books of social observation. The Years (2017; Les Années, 2008) is a collagelike history that tracks a changing France between 1941 and 2006. In Look at the Lights, My Love (2023; Regarde les lumières mon amour, 2014) she charts her visits to an Auchan supermarket in her hometown of Cergy-Pontoise, in the northwestern suburbs of Paris, over the course of a year. Exteriors follows suit: it is her record of public life in Cergy between 1985 and 1992, as she observes fellow passengers on RER and Métro trains and platforms, customers in the hair salon or at the supermarket, and notable articles in Le Monde and Marie Claire. The book is less about Ernaux than many of her others – such as Simple Passion (2003; Passion simple, 1991), the tale of her secret affair with a younger married man. Yet in viewing strangers, Ernaux better sees herself. ‘It is other people – anonymous figures glimpsed in the Métro or in waiting rooms – who revive our memory and reveal our true selves through the interest, the anger or the shame that they send rippling through us,’ she writes.

The MEP exhibition makes this mirrorlike link between the other and the self ever more profound. Hiro’s Shinjuku Station, Tokyo, Japan (1962) – which comprises seven separate images of people squashed onto a commuter train, and in total stretches to more than five metres in length – is a claustrophobic capturing of the sights and smells, the pushing and shoving, on rush-hour trains. One young woman, on the far-right of the image, is squashed against the doors, cradling her bag, her expression glum. She is a good head shorter than the suited men who crowd behind her, and looking at her I was reminded of the gendered reality of the scene: that I, too, am too short to hold onto a rail hanging from a train’s ceiling, that it is inevitably a man’s armpit with which I find myself at nose-level. In the next room lies Dolorès Marat’s 1997 Les jambes (Legs), which shows a closeup of the back of a woman’s calves as she stands on an escalator. They are just legs, but the photo is taken from a position far below an adult’s eyeline. I felt disgust thinking how my own legs might look if someone were to photograph them from that angle, and so closeup.

Many of the photos in the exhibition are taken through windows or glass partitions, giving the viewer the feeling that they are snooping, or peering where they aren’t welcome. In the very first image we encounter in the exhibition, by Claude Dityvon, a woman pauses to hold open the door to an apartment block. Through a glass panel to the right, we see the vague outline of a man in a helmet, four people clustered around him. Further beyond the central woman, another is walking through a second set of glass doors. And on the other side of her stands a man, visible yet separated from us by two transparent surfaces. The photograph is titled Aprés l’incendie, Les Olympiades, Paris 13e (After the Fire). Just like Ernaux’s precise written depictions of impassioned moments, it holds a stillness. There is little sense that this tranquil scene has recently been the site of an emergency. Like the glass’s transparency – at once providing clarity and an erected barrier – it is deceptive.

In 1992 Ernaux watched two homeless men as they engaged in ‘verbal sparring’ on a train. They ‘performed with ostentation for the benefit of the twenty-odd passengers travelling in the RER carriage’, she writes in Exteriors. ‘But, contrary to a real theatre, members of the audience here avoid looking at the actors and affect not to hear their performance. Embarrassed to see real life making a spectacle of itself, and not the opposite.’ We see how public spaces provide a stage for performing identity in these photos too. Though Ernaux climbed the social ladder, moving from her rural, working-class upbringing to become part of the university-educated class and then the literary elite, she holds her class origins close in her writing. In her Nobel acceptance speech, she spoke of how in her twenties she promised to “write to avenge my people”. She knows that to record that which is more often overlooked is to respect it, to give it credence. These collected photographers know that, too. In Bernard Pierre Wolff’s Couple de toxicomanes, 14e rue, New York (A Couple of Drug Addicts), taken in 1975, a pair of people embrace in front of a sandwich shop. Their faces are concealed: we cannot see whether they are kissing or sobbing. On the other side of the shop window, a man sits, looking on. It is just a mundane urban scene, but the photograph’s composition asks the viewer to both watch and be watched. Does voyeurism come with power, it asks, and in which direction?

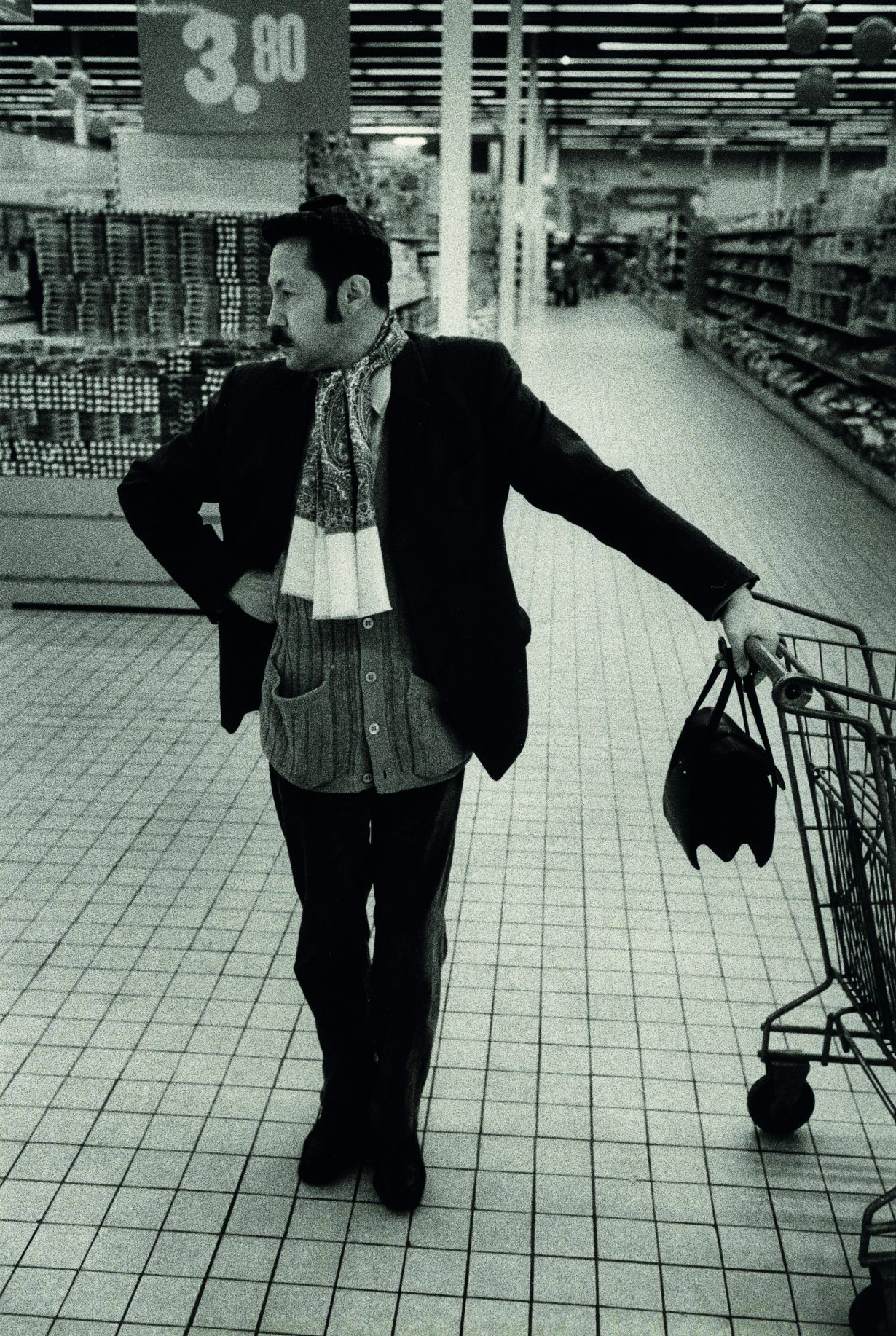

The title of Jean-Philippe Charbonnier’s “Où qu’c’est qu’elle est passée?”, Carrefour, Villiers-en- Bière” (“Where on earth did she go?”, 1973) asks us to imagine what is happening outside the frame. But at first the photo’s subject is too enthralling to look away from. A moustachioed man with prominent sideburns and a paisley scarf around his neck stands, one hand on his hip, the other on a trolley, in the aisle of a supermarket. His marvellous campness is a contrast to the sparse white tiled floor that stretches out behind him. He is captivating in himself, yet it is what he makes me think of next that is even more intriguing. Who is the woman he waits for? What kind of life does he live beyond the supermarket? Does he consider himself to defy societal expectations of masculinity?

In this merging of Ernaux’s powerfully personal words with the photographs’ anonymous subjects, the exhibition gestures both to the significance of individual stories, and to the importance of setting one’s personal understanding of oneself in the context of other lives. ‘It is outside my own life that my past experience lies,’ Ernaux writes. This exhibition shows that it is also inside the individual, among each other, that we find a wider truth.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger is a writer and editor living in London. She is assistant culture editor of the New Statesman and has also written for Dazed & Confused, the Observer and the i.