Faith, Hope and Carnage – intimate discussions between the singer-songwriter and journalist Seán O’Hagan – transcends the genre of the rockstar memoir

In 2020, during the first weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown, journalist Seán O’Hagan spoke regularly on the phone with Australian singer- songwriter Nick Cave. The pair had known each other for over 30 years professionally, but as the pandemic deepened O’Hagan found their chats becoming more ‘open and illuminating’. An idea for a book hatched, inspired by the long-form interviews pioneered by the Paris Review, ‘revealingly intimate’ discussions ‘exploring the impulse to write’. And so, from August 2020, their interviews over the course of the following year formed the basis of this extraordinary, intensely personal book.

At first, the notion of ‘a conversation’, as the book bills itself, seems disingenuous – by the nature of the project the majority of the words on the page must be Cave’s. But as the book unfolds, and Cave begins to ask O’Hagan his opinion on work in progress (the recent Carnage album), a conversation does indeed evolve.

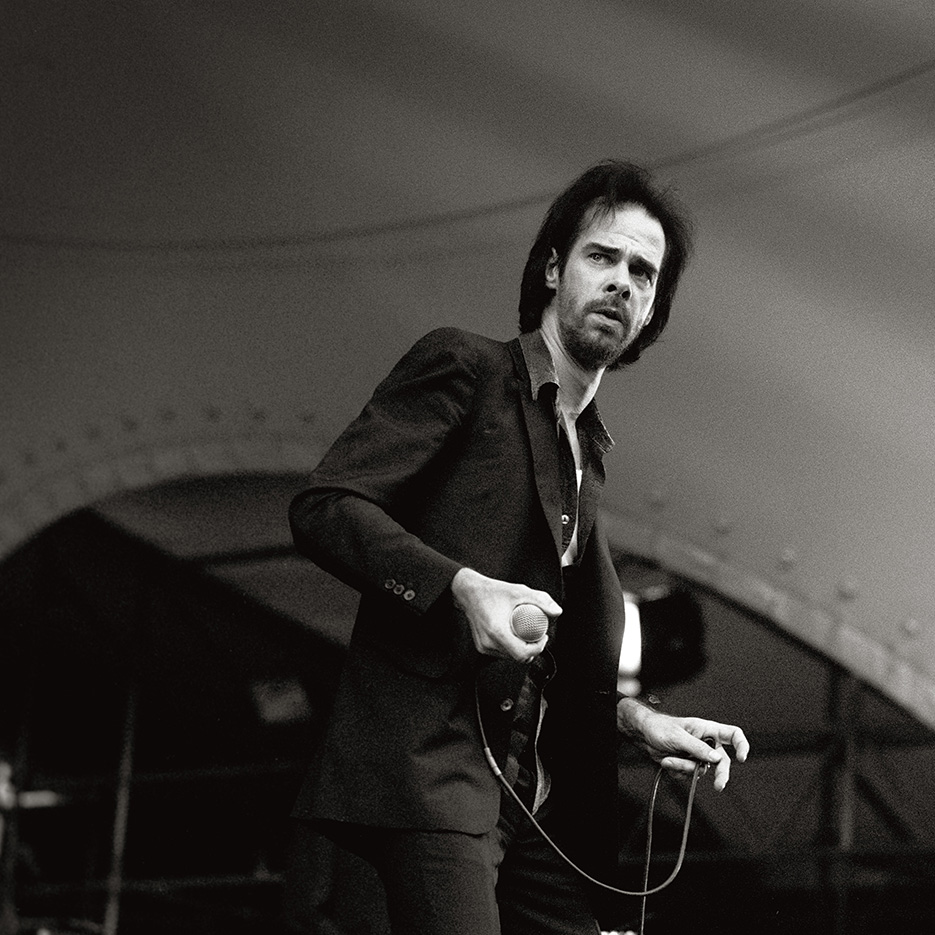

Cave, who claims to hate interviews, opens up about ‘creativity, collaboration, belief, doubt, loss, grief, reinvention… the endurance of hope and love in the face of death and despair’: big, serious – even unfashionable – subjects that he discusses with eloquence and humility. We warm to his voice: compelling, lucid, entirely devoid of self-pity, fiercely intelligent. On his reason to make art, and its beneficent value to his audience, he submits: ‘The work I do is entirely relational, actually transactional, and has no real validity unless it is animated by others.’ This synergy is necessary for his creative process, too. On his collaboration with Warren Ellis for the Ghosteen (2019) album he writes, ‘we are trying to arrive at a formal song through the perilous process of improvisation.’

Elsewhere, Cave talks about his complex relationship with religion – ‘doubt becomes the energy of belief… It is the unreasonableness of the notion, its counterfactual aspect that makes the experience of belief compelling’ – and his early creative impulses. At art school in Melbourne during the 1970s Cave had set out to be a painter, but confrontational rock music took over. ‘The vitalising element in art is the one that baffles or challenges our outrages… As a young musician, I felt it was my sacred duty to offend.’ Later, Cave’s formal training is put to use in his songwriting: ‘I seem to experience the world visually, through stories and symbols and metaphors… And that is the way I write songs – as a series of highly visual images.’

There are flashes of wry humour, too. Cave describes his younger self as ‘an egomaniac with low self-esteem and a sex drive’, although forays into his past as the hellraising singer of The Birthday Party swiftly peter out – such stories belonging in a rockstar memoir, and Faith, Hope and Carnage transcends such a tired genre. This is largely because the overarching subject of the book is the death of Cave’s teenage son, Arthur, in 2015, and the ensuing maelstrom of grief he and his family experienced. ‘It felt like our lives had been poured down a fucking hole’. Cave describes feeling in ‘a place of acute disorder’; throwing himself into work recording the album Skeleton Tree (2016), while admitting ‘I didn’t know what I was doing’. At times, it’s almost unbearable for the reader to be close to such visceral, private grief. This, though, is one Cave’s themes – people don’t discuss grief, they find it uncomfortable or impossible; words prove to be inadequate tools for the job.

Through O’Hagan’s sensitive questioning, Faith, Hope and Carnage is one of the most powerful and affecting meditations on grief and loss published in recent years, alongside books like Nick Blackburn’s The Reactor (2022). Cave’s ongoing recovery, which has seen him turn to making a series of ceramic figurines depicting the life of the devil, has resulted in a benevolent, life-affirming worldview. He concludes that we must extend ‘a quiet but urgent love for those who remain, a tenderness to all of humanity, as well as an earned understanding that our time is finite’, a sentiment that the reader, having followed Cave’s arduous journey, will find hard to dispute.

Faith, Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan. Cannongate Books, £20