During the course of a career spanning more than 50 years, Bridget Riley has established herself as a major figure in abstract painting and printmaking, relentlessly investigating the optical and emotional possibilities of colours and shapes. Widely known as an icon of Op art, Riley first came to prominence in the 1960s – notably after her participation in The Responsive Eye exhibition at MoMA in 1965 – creating visually disruptive black-and-white paintings that actively engaged the viewer’s perception, using geometrical patterns that were quickly taken over by the fashion and design industries throughout the ‘Swinging Sixties’.

Riley represented Britain at the 1968 Venice Biennale, at which she received the International Prize for Painting. Despite this early fame and popularity, the artist refused to wallow in the formal innovations of Op art, and pursued her experimentation by moving on to colour in vertical stripe paintings. Her interest in the diffusion of light through colour resulted in variations of shapes and palettes producing the effect of warmth and vibration. Her art became one of pure visual sensation, with colour and shape as ‘ultimate identities’ interacting on the canvas. During the 1980s, Riley’s work took another turn when she introduced the diagonal line in her paintings, shattering the picture plane into multiple lozenges and intensifying the sensation of rhythm and movement. Shapes seem to advance and recede from the surface, coming back to the study of contrasts present in her early black-and-white paintings. In her more recent work, the very geometrical constructions have evolved into more fluid and swaying arabesques defining larger and uneven planes of softer colours, reaching another level of complexity.

Long stuck with the reductive label of Op artist, Riley has established herself as a major modern painter in line with a tradition that reaches back to Seurat’s pointillism and Matisse’s cutouts. Supported by her extensive body of writing, Riley’s art and continuous research has been – and still is – a major influence for generations of artists, reaching beyond the realm of painting.

Andrew Bick

‘I am more interested in Bridget Riley’s interconnectedness than relative isolation as the ‘only’ British hard edge painter of her generation to become internationally renown. Her collaboration with Ad Reinhardt for Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Poor.Old.Tired.Horse is a personal favourite and this modest book is the perfect example of such connectivity. They met having both been in The Responsive Eye at MoMA New York and Reinhardt became something of a mentor to the young Riley, taking a protective attitude with copyright breaches of her work by the New York fashion world.

Bridget Riley illustrates and Ad Reinhardt, in his distinctive handwritten script, writes some of the art as art aphorisms for which he is renowned. Riley uses a double tilted ellipse in various combinations that suggest the letter ‘O’ seen from different angles and cut-and-pasted the layout of Reinhardt’s text -fragments in rotated blocks throughout the eight page booklet. A beautiful and humble object, where neither artist plays the dominant role, thus sits perfectly in the world of concrete poetry for which Finlay was such a catalyst in the 1960s, suggesting real friendship between the two artists skilfully exploited by the publisher. It reminds me to look for the catalytic and generative aspects of an artists’ practice, rather than for their lionisation as hero of a movement or best in class.’

Laura Buckley

‘I first observed Riley’s work as a teenager growing up in rural Ireland, in the books that were available to me at the time. Hers was a unique process, a vision of how I imagined the future could be.

A directional, swaying movement that could be so graphic and mechanical, yet cause such a surge of energy within the mind of the viewer. Those controls that force you to dart from here to there, then back into your own head. The comfort of rhythm and strange signals of sound waves and warped messages.

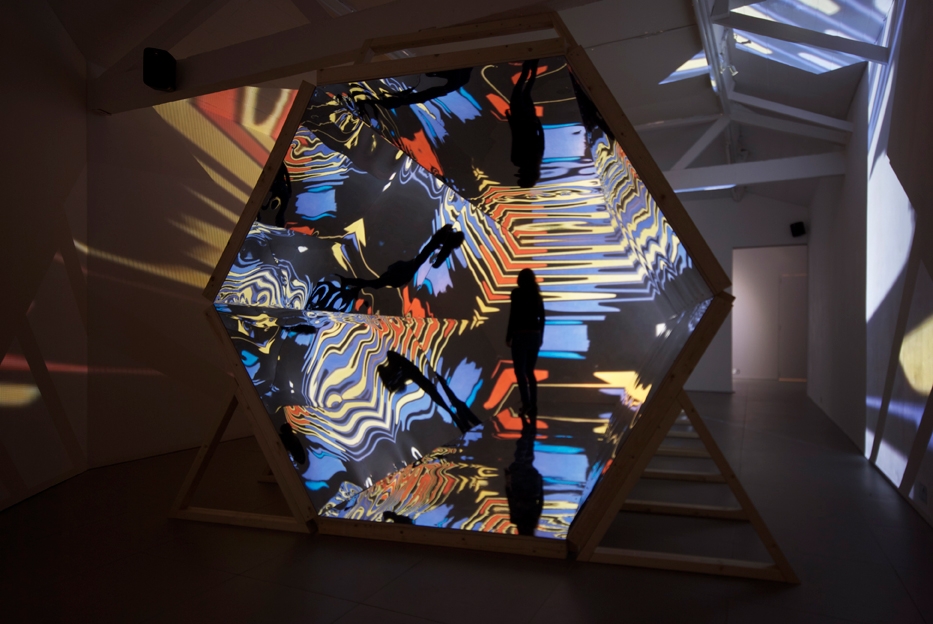

Riley’s influence is there in what I do, graphic and directional patterns are repeated and move in 360 degrees, stepping off the canvas or out of and away from a situation. To break out of the tedium of our existence, or perhaps just to enhance it somehow for a while.’

Claudia Comte

‘Bridget Riley has played an important role in the development of my work. In my paintings, on the walls, in installations or in my shaped canvases the hard-edgeness, clean order of things, the system of rhythms of lines and shapes are highly inspired by the lineage that Riley is part of. What I attempt in my work is to extend this manner of thinking into the three-dimensional. I break the clean-cut compositions or the so called ‘Op art’ effect by adding loose brushstrokes, by placing hand carved wood panels in front of my ‘clean’ wall paintings and my monochrome surfaces and thus break them with a rough gesture. Bridget Riley has inspired an entire generation of artists who followed her and who in turn influenced my work. In essence her work showed me what painting and the line can affect beyond the two-dimensional without it loosing its importance.’

Jane Harris

‘I feel as if Bridget Riley has been a distant mentor for most of my artistic life. It’s almost impossible to put into a few sentences the impact her canvas paintings, works on paper and wall paintings have had on me. Her own development, with its shifts in emphasis and orientation achieving sometimes apparently contradictory outcomes, has been stimulating and inspirational. She reassures me of the continuing importance of painting. I concur wholeheartedly with her belief that for a painter, it is essential that thoughts are formulated through the interlinked acts of looking, sensing and doing.

Her career has been of unceasing commitment to making art in a critical, insightful and uncompromising way and her writings on art and perception are not only instructive but also a joy to read. Always an artist of the present, what I admire enormously is how, through very particular and precise research and argument, she relates her painting to painters of the past in such a meaningful and relevant way.’

Neil Rumming

‘Bridget is a Titan. An artist whose examination and rigour in painting is hard to match. She gives me a headache both philosophically and physically as I find her work visually repellent and uncompromising in its intention to test the parameters of space and colour. Her influence has seeped into all aspects of culture and has undoubtedly had a profound effect on subsequent generations of artists, designers and illustrators. This feels like an obituary, it is the exact opposite, it is the affirmation of a potent force in visual culture and an artist who’s investment in the act of painting is difficult to quantify as she helped to alter the dynamics of how a painting is both conceived and transmitted. Her influence upon my work has not been triggered by a specific painting but like most cultural phenomenon, Bridget’s shadow has crept onto the fringes of my consciousness where it has remained, indelible and concrete in its assertive energy.’

Esther Stocker

‘Bridget Riley, I love your art!’

Mark Titchner

‘In his theory of General Semantics, Alfred Korzybski argued that human knowledge of the world is limited by the structure of language and the human nervous system. In the work of Bridget Riley we find the trusty eye and the trusty world exposed as flaming eternal mandalas are brought forth via hard edge geometry.

In 2003 when offered the opportunity of Tate Britain’s Art Now space concurrent to Riley’s retrospective (which took place in the adjacent galleries) I developed a work called Be angry but don’t stop breathing; for all intents and purposes a group primal scream device. Reducing language to a scream was my attempt at an equivalent for what one experiences confronted by works like Blaze 1 (1962), Shiver (1964) or Climax (1963) and the nausea of experiencing the world as it is rather than as it seems.’

Heimo Zobernig

‘Bridget Riley is one of the most influential artists of the last decades, and with her radical and at the same time playful work she affected generations of artists. The term ‘Op-art’ is inseparably connected with her. It is unique how she developed her work constantly and how she managed it to include all aspects of visual experiences. An incredibly wonderful body of work. The pleasure and also irritation that her work created in matters of perception, are an unfailing source for further inspiration. The success and the failure of those effects means elegance and precision in its performance. Like no other artist, she succeeded in creating a body of work that seems ageless, an artist of the century without personal mannerism, GREAT.’