While trawling through the interminable displays at Frieze Art Fair in London in 2011, Gay Gassmann, an art historian formerly with the Getty Museum, was, for the first and only time that day, stopped dead in her tracks by a work of art. The piece, which was hanging on the exterior wall of the of the Lisson Gallery’s exhibition stand, was a wall-size digital photograph of an exotic-looking building on a city square. Leaning closer, Gassmann saw that it was not a single image but a pixelated composite, made of thousands of smaller images of the same city square, each shot at different hours of the day. The work, Dis-Location 4 (2007–8), was by Rashid Rana, a Pakistani artist from the Punjabi capital of Lahore. Its composite and constituent images were of that city’s bustling Lakshmi Chowk crossroads.

Gassmann’s wheels started turning. A Paris-based art consultant best known for her longtime association with Peter Marino Architect, for whom she oversees special art projects and commissions, Gassmann does not collect art: she ‘places’ it, mainly in the flagship stores of fashion brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton. Marino, the go-to architect of luxury fashion retail, uses contemporary art to add extra sizzle and buzz to his interior designs. Because of this strategy, his firm is one of the biggest sourcing agents of private commissions in the contemporary artworld.

Would the artist be interested in a commission, she asked? Probably not, said the gallerist. He explained that Rana’s art – software-generated composite photomontages that hang on the wall or digitally drape three-dimensional objects – had been caught up in the recent South Asian art boom and, overwhelmed by the unexpected attention (“It was too crazy,” Rana told me, months later, during a breakfast interview in a Paris café. “I could have sold anything.”), the artist had scaled back production and returned his focus to teaching. Rana is the head of the fine-art department at the Beaconhouse National University in Lahore, and one of the founding faculty members of its School of Visual Arts and Design. Teaching had long been the principal source of his livelihood, and this gave him a certain freedom to ignore the voracious demands of the global art market.

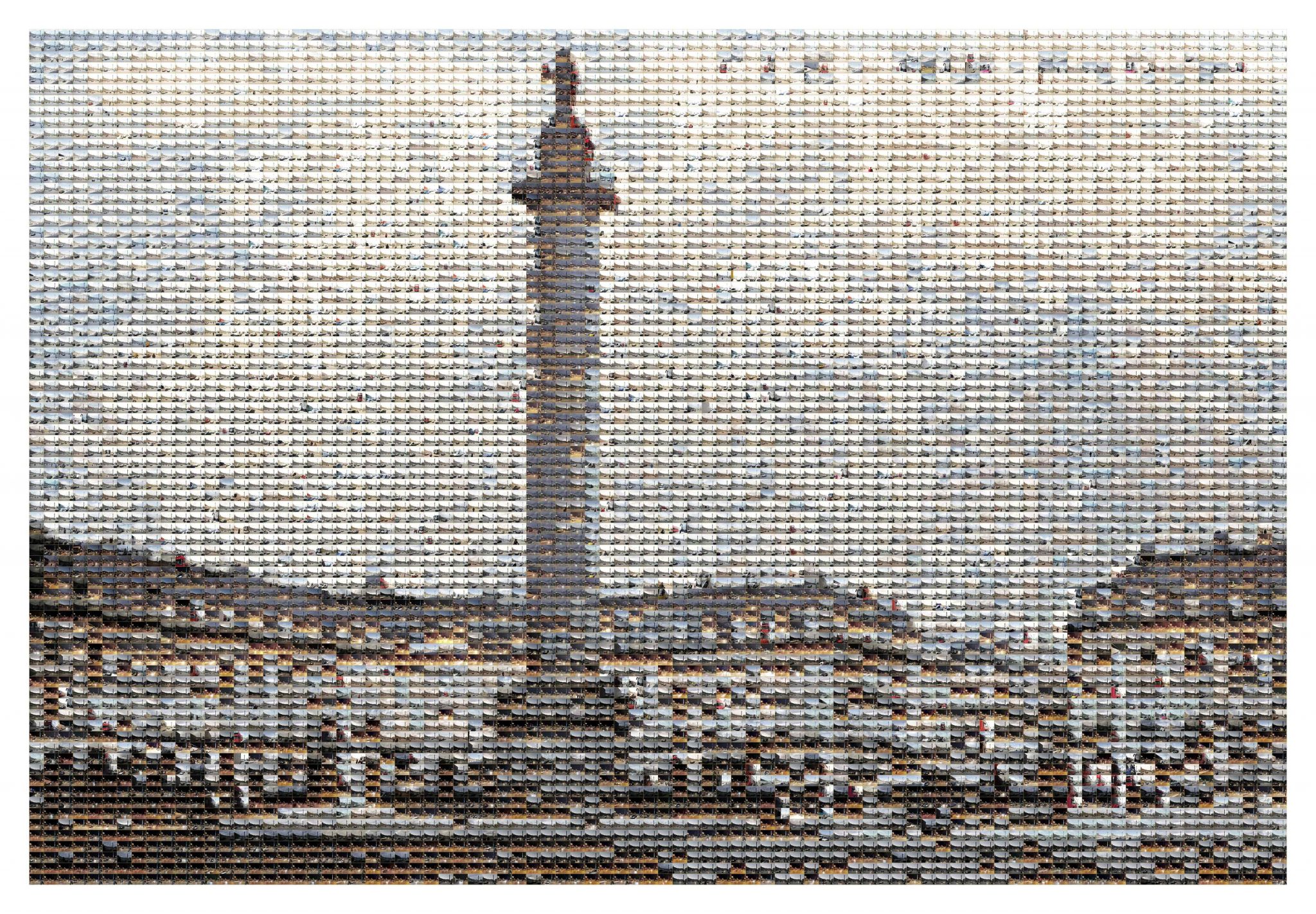

Undeterred, Gassmann persisted. She had encountered artistic reservations and resistances before; and more often than not had swept these aside. She and Marino contacted and courted the artist, and some eight months and 20,000 photographs later, Dis-Location 5 (2012), a unique, 188 x 270 cm ‘time-based’ depiction of another famous city square – the Place Vendôme in Paris, home to Napoleon’s Vendôme Column and some of the most expensive jewellery shops in the world – was installed on the Place Vendôme itself, in the lower-level VIP area of the new Louis Vuitton jewellery and watchmaking boutique, just around the corner from the Hotel Ritz, and just in time for the store’s official opening.

Rana and his team of photographers had to overcome several obstacles to construct this unobstructed view of Napoleon on his plinth, towering over the glittering facades of big-ticket luxury. Scaffolds were cropped out of the image, as were all signs of an ongoing renovation project at the Ritz, and of construction resulting from a fire the previous year in an underground parking lot. The months of work – at the site and back in Rana’s Lahore studio, where the micro images of the Place Vendôme were used to digitally compose its macro image – paid off. Dis-Location 5 is a visually arresting image, formally stimulating and decorously beautiful.

However, for an artist whose work has always been closely tied to ‘the Orient’ and textbook east/West divides and dichotomies, it represents a certain untethering. Is there any Lahore in the jewellery store? Following his trajectory from his hometown – a central subject for most of his work – to Place Vendôme in Paris, appears to be, in itself, a lesson in dislocation. Yet as Rana’s work demonstrates, appearances can be deceiving.

Rana has consistently defied the expectations that different artworlds have made of him. Trained in traditional painting techniques, including the miniaturist techniques that dominate the Lahore region’s art scene, he turned to digital media and photography in the mid- 1990s. This led to a broader and more provocative set of concerns. I Love Miniatures (2002), his breakout piece, is an early example: a Mughal emperor’s miniature portrait composed of tiny photographic images of advertising billboards in Lahore.

His worldwide notoriety comes from work that has never been shown publicly in his home country: Veil (2004), a series of giant images of women dressed in burkas entirely composed of tiny Internet-sourced shots of hardcore-porn stars from the West. This was followed by the Red Carpet (2007), large photomosaic images of traditional Oriental carpets composed of tiny images of Lahori slaughterhouse carnage. In the series What Lies Between Flesh and Blood (2009), Mark Rothko-like forms are constructed out of thousands of closeups of bruised or bare pornographic flesh.

This vein of work, sensational, deliberately controversial, is the Rana that the market craved – the first Red Carpet sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2008 for $623,000, the highest price ever paid for a Pakistani work of art. And it is the vein that Rana has turned his back on to explore more formal conceptual concerns. “My work is often a three-way negotiation between myself, my immediate physical surroundings and what I receive – whether through the Internet, books, history or collective knowledge,” Rana told me in Paris. “But I am at this time and age seeking another kind of universality. Visual language can reach people but still retain its own accent. It can retain its own specificities, yet be transnational.”

The Dis-Location series is an example of this arguably less politically charged and more mature vein of work. As are his photo-sculptures: screenprints of benign, everyday objects – a vase of flowers, a newspaper, a book – printed onto three-dimensional objects.

“I want to take my work to another level by focusing more on form and less on political content,” said Rana. “But you can never avoid it, you know. Even if I just pick a random selection from my own bookshelf [Books (2010) prominently displays a Jacques Derrida title on the top of its pixelated pile], you start seeing meaning in it. Fine, if it’s there, it’s there. I just try to reduce it as much as I can, and allow you more of a chance to look at the formal aspects of it.”

When we met, Rana was toying with the idea of adding a political element to Dis-Location 5. Place Vendôme’s giant equestrian statue of Louis XIV was toppled and destroyed during the Revolution, and then the column Napoleon replaced it with was pulled down during the Paris Commune. A younger Rana might have pixelated these historical moments into the mix. This time he decided against it – whether for aesthetic, political or politic reasons, we’ll never know. Yet as store decor, Dis-Location 5, still buzzes with associative frisson, in ways probably not intended by the artist or his patron. It brings to the fore a dilemma forever facing not just contemporary artists, but all art exhibited contemporaneously.

As the American art critic Dave Hickey puts it pithily in The Invisible Dragon (1993), art “outside the institutional vitrine… is never not advertising and never apolitical”.

Rana’s work for Louis Vuitton (he has since started another Dis-Location commission for the brand, a pixelated composite of the Vienna State Opera house for the Louis Vuitton flagship store in Vienna) represents a type of homecoming. Having bumped into one limiting condition of art – the pornography re-presented in Veil – he has returned full circle to the other defining extreme of art: the commodity advertising he depicted in I Love Miniatures.

Of course, one never just goes home – and Rana seems perfectly comfortable where he is. “The political thing was just a phase that one goes through,” he told me in Paris. “I am enjoying another kind of phase. And I don’t have an uncomfortable relationship with money or luxury. I have a nice car because I can afford it. In Lahore, we live so many lives, all at the same time. We have a Mercedes-Benz and a horse-drawn cart – the design of which hasn’t changed in 3,000 years – both driving down the same road. When I did the stove piece [Stove (2010), a three-dimensional pixelated depiction of a rustic cooker], someone said, ‘Is this a reference to women-burning in Pakistan?’ I didn’t think of that… But if someone brings that meaning into it, I won’t stop them. Meanings are changing all the time. Some, not all, expect me to make works like Red Carpet and that kind of stuff. I am sorry to disappoint them, but I’m not doing that now.”

This feature originally appeared in the May 2013 issue of ArtReview