American artist Nancy Holt has made some of the most significant contributions to Land art, in particular with her monumental Sun Tunnels (1973–6) in Utah, but her wide-ranging practice includes photography, film and video, installation and sculpture. In the midst of a major touring retrospective, Sightlines, the artist discusses her pioneering work with ArtReview.

Laura McLean-Ferris In London we’ve recently seen an exhibition, Photoworks, at Haunch of Venison that concentrated exclusively on your photographic work. What was that like for you, putting works together in a single form of media? Do you think of photography as a separate part of your practice?

Nancy Holt: It’s the first totally photographic exhibition I’ve had. It had been a desire of mine to exhibit all the photographic work together in one place, and then Ben Tufnell [at Haunch of Venison] came along and made it possible. Printing the photographs in New Mexico, and then finally seeing the photographs installed well at the gallery, felt new and fresh to me: I made connections I had not thought of before and it was very satisfying.

It was interesting how the concentration on the photographs threw a different light on your sculptures and Land art works and brought out the cameralike qualities of those. Many of your sculptures are framing devices in the landscape – perceptual structures that allow viewers to become aware of a site and their particular position in space.

In the 60 Western Graveyards photographs [1968], I’m framing what I’m seeing, but at the same time each grave is uniquely delineated, outlined one way or another with various materials – dilapidated fences, railroad ties or stones – so in a sense I’m framing a frame through the camera. You see that consciousness of framing through the camera, and a sort of double framing, very early on in my photography. And in an even earlier work, Concrete Visions in 1967, I’m looking through holes in concrete blocks and moving closer and closer in until there is only the view through one hole, so the framing of the camera and the framing of the concrete is made very palpable.

Even when I was following a walking trail in Dartmoor [Trail Markers, 1969] and following the orange circles on rocks and posts which marked the trail, I was also framing the circles in my camera. The framing carried into my sculptures, like the Locator works begun in 1971 and Views Through a Sand Dune [1972]. The Locators are not only to be looked at, but also to be looked through. Often the Locators are opposite each other, so through one Locator you see the other. When you look out the other way through the Locator, you’ll see the environment encircled in your vision. You are aware of your own perception – seeing your own sight.

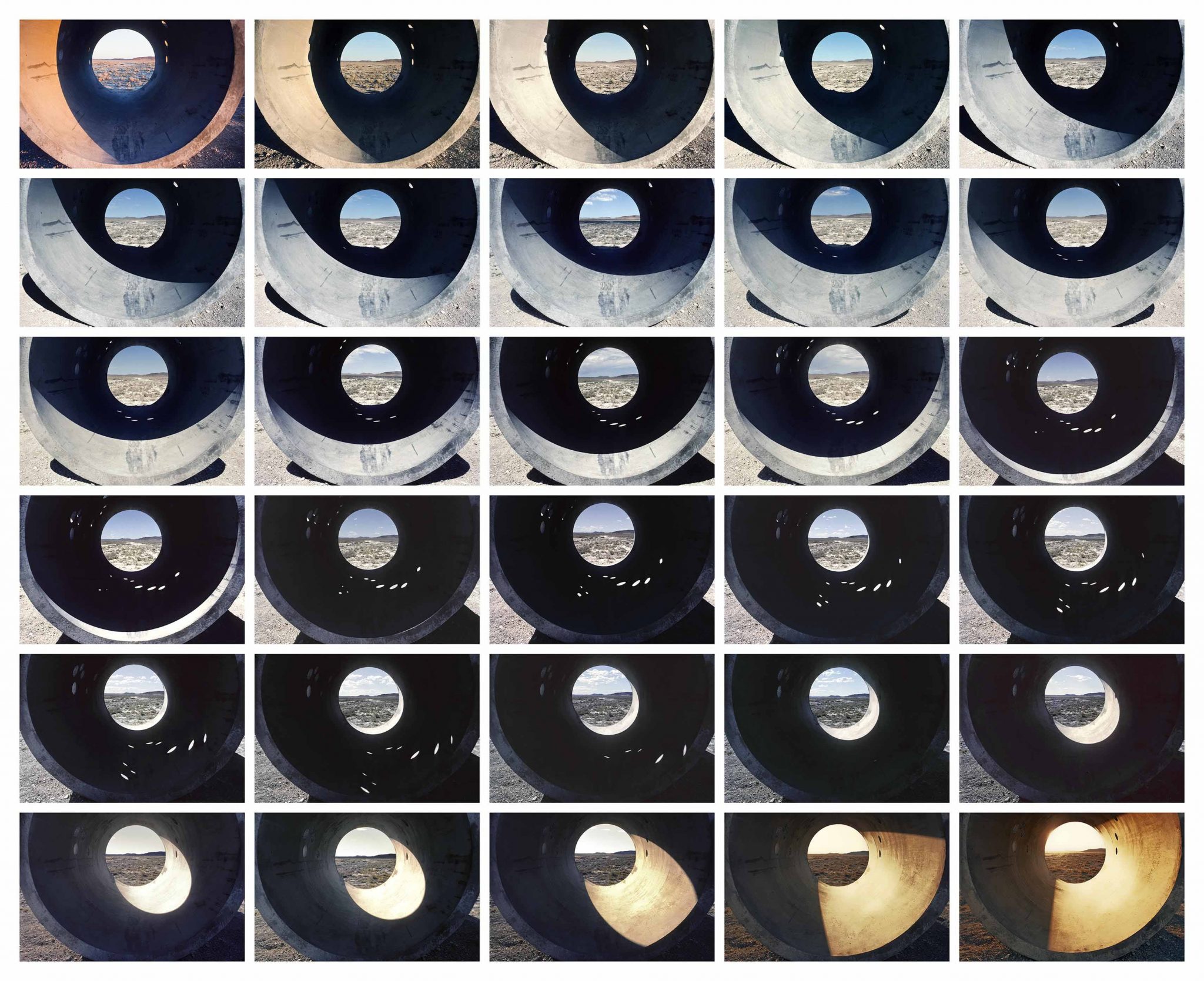

For one of your best-known works, Sun Tunnels, you placed four concrete tunnels in the Great Basin Desert in Utah [near Spiral Jetty, 1970, by Holt’s late husband, Robert Smithson], which are positioned so that they frame the sunrise and sunset on both the summer and winter solstice. They also have holes drilled into them in the pattern of star constellations. Could you tell me about the decision to include constellations in that work?

Our sun is one star in the universe, casting its light through the star-holes in the top halves of the Sun Tunnels, making everchanging spots of light in the bottoms of the tunnels. Only when the sun is directly over a hole will a full circle of light be cast, the rest being pointed ellipses (mandorlas) and slivers of light. You walk through the tunnels at midday and you’re walking on stars – sun/starlight that’s been cast in the pattern of a constellation at your feet. Choosing which constellations of stars was an aesthetic decision. I tried lots of different constellation patterns using different star maps. If you start looking at star maps you’ll see that over the years, depending on the time and the mapmaker, there’ll be different stars included or excluded in a certain array of stars called a constellation.

I discovered this when I made my work Hydra’s Head, next to the Niagara River, in 1974. Then when I went to Utah the next year I started working with different constellations, trying to decide which ones I wanted in Sun Tunnels. There had to be enough stars of different magnitudes, since the diameters of the holes change relative to the magnitude of stars, and the constellation had to wrap around the top half of a cylinder in a way that was interesting and had some holes at eye level so you could look through them.

It struck me when watching your film about Sun Tunnels, which was recently screened at the ICA, that you were the only woman both on the construction site where the concrete tunnels were being made and at the site of the artwork. Did that present any difficulties for you?

When a vision is strong enough, then the intensity of the desire to make the art seems to obliterate many obstacles. I was not thinking about gender when I was building Sun Tunnels. The project was unusual enough that it tweaked people’s interest. So I think what happened was that the workers, almost all males, were affected by the seriousness of the project, by the uniqueness of the project, it broke down their habitual ways of thinking, and then they got caught up in the challenge and adventure of it.

The concrete footings had to be poured very quickly, isn’t that right?

The length of time it took the cement mixing truck to get from its source out to the desert site did not give us any extra time. Two workers and the truck driver had to dump the concrete into the footing forms as soon as the truck got there. The concrete would have hardened in the cement mixer if we had waited too long.

Did you know that when you picked the site?

No, not when I chose the site. I was lucky they were building a highway not too far away, in Oasis, Nevada. I pursued the construction company owner, made numerous phone calls, finally tracking him down, and he ultimately agreed to send the concrete mixing truck. Yes, it was a synchronicity – my life is full of synchronicities.

Those synchronicities are something you have discussed in relation to Wild Spot [a 1979–80 sculpture comprising wildflowers encircled by two fences, sited at Wellesley College, in Massachusetts] in the diaristic writing connected to it. Here you talk a series of personal coincidences and the emotional throwback that you experienced when asked to make a work for Wellesley, a college that your mother had wanted you to attend, and who rejected your application. I like what you say about the fact that there are events or memories that you can’t ‘garden’, much as you try.

These emotions can come unexpectedly and stab you deeply: they seem to come out of nowhere – unresolved issues lying around in one’s psyche. Returning to a particular place associated with certain memories can trigger these feelings: the external trigger activates the internal trigger. At Wellesley I let the storm of my emotions blow through, let the stabbing happen, while being present to it – feeling how it was affecting my body, and noting what thoughts were associated with it. Wild Spot also refers to that wild, uneducable, untamed zone in the centre of ourselves.

Your Systems works, in which pipelines, electrical cables and ventilation systems run through a gallery space, have a political aspect to them, most obviously with Pipeline [1986], installed in a gallery in Anchorage, Alaska, which dripped oil, recalling the nearby Trans-Alaska Pipeline. But even in other related installations that present adapted electrical, heating or air systems, there is this political aspect to them, isn’t there?

When I made Pipeline the Trans-Alaska Pipeline had been for years leaking oil here and there into the landscape, and there was much concern about the environment. My work was calling attention to the oil leaking, so in that respect it was definitely political. It was very courageous of the staff at the Anchorage Visual Arts Center to exhibit the work, because the gallery had received funding support from the oil companies. All of my Systems pieces had a political aspect, even the very first one, Electrical System (For Thomas Edison) shown at John Weber Gallery in New York in 1982. The entire work – an interconnecting electrical conduit that filled the room – emanated from an electrical outlet box, very visible on the gallery wall. So the work called attention to the electricity coming out of this box, but the question is: just what is the source of the electricity? The lightbulbs in Electrical System were lit by the transformation of coal or oil or plutonium into electricity at a utility company, Consolidated Edison, in New York. The dedication to Thomas Edison also led people to think about electricity: the world before electricity, can you imagine? That was only in the late nineteenth century, really so recently! Edison put a series of lights in a line, and I wasn’t doing anything more than that in the installation. It was really going back to the basics of electricity: the current going through the steel conduit, making light. In the lightbulbs I used you could see a filament arc of electrical light.

That piece reveals that we don’t really consider electricity to be related to the landscape: it actually has to come through the land, either overhead or underground – similar to the water or ventilation systems.

Air, water, electrical current, like lightning, are basic elements of the planet. Air circulates through the Ventilation System works, and in Waterwork and Hot Water Heat, water comes in through pipes from a vast underground system that begins at a reservoir, which in turn is fed by the rivers and the rain. The outgoing water ends up in a drainage or sewer system, is treated and often returns to the ocean. Electricity is made from the bowels the earth – from energy converted from the oil, the coal, the plutonium.

It’s a really interesting approach to see Land art entering the white cube gallery space in such a way. Your mind is going outside, following those tubes and cables or pipes, connecting the inside and outside, and asking the viewer to consider existing systems in the land.

The pipes are going into the ground, traversing beneath the streets of the city and carrying energy and substances from the earth. Our life indoors is intertwined with life outside, with the whole planet, actually. When we turn on the light, we think, ‘Oh, we have light.’ We’re just so used to it even though electrical light has only been around for a century. All we have to do is turn on a small switch and there is light. By externalising and exposing the system, which is usually hidden in pipes, conduits and ducts behind the wall, there is more of a sensation of the electrical current or the water or the air moving through. You might start to think about its source. I know people did think about that.

Several of your works create events with the sun. Dark Star Park [1979], a large-scale artwork which is also a park in Rosslyn, Virginia, includes large spheres and poles that have permanent shadow patterns in the ground. These fall into exact alignment with the actual shadows of the spheres and poles on the anniversary of the date and time that the land was purchased to build the town, whereas Sun Tunnels marks the two solstices. Some of these works have generated regular social events or actions that have begun to occur independently. Is this aspect interesting to you?

Yes, some of the works have generated public interest beyond what I ever imagined. My work Solar Rotary, at the University of South Florida in Tampa, celebrates six different dates each year, people especially gathering on the summer solstice at solar noon to see a circle of sunlight surround the central circular seat, or sometimes on one of the other five days to see a circle of light line up with a round historical plaque in the pavement. I’ve also had the experience of people taking ownership of the sculpture immediately, as with Stone Enclosure: Rock Rings at Western Washington University, north of Seattle in Bellingham. I always do my own photography of my outdoor sitespecific works – I consider the photographs of the work my art as much as the sculptures themselves. Often I like to have one person in the photograph just for scale, but I don’t want a lot of people, so right after I finished Rock Rings, I was out there in the right light waiting to shoot it, and there were just too many people in and around it. I went over and tried to shoo them away politely: “I’d like to take a photo, please could you move, I’m the artist.” In response they said: “This is our sculpture. We’re enjoying ourselves here, we’re not going anywhere.” Somehow it didn’t matter that I was the artist.

This is an amazing aspect if you consider that so many artists start off trying to generate these social situations in their work, but couldn’t dream of a situation where people actually get together several times a year of their own accord.

I’m really awed that this happens. I cannot control it, it happens on its own. During the last few years, with all the information on the Internet, I can now keep track of the local activity at my sculpture sites. A link to a local paper will inform me that people are out at Annual Ring celebrating the summer solstice, and they show people holding hands inside the sculpture. They mention that this has happened other years as well. I also keep an eye on Dark Star Park. Often the media is there televising or photographing the alignment of the shadows on August 1 at 9:32 AM, and the local people named the day Dark Star Day, which was made an official day at the events celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Dark Star Park in 2009. With Sun Tunnels, of course, every year there are groups of people from all walks of life, who go out for the solstice, especially the summer solstice. I’ve known artworld people who think they’re going to go out to see Sun Tunnels and have a quiet experience and time alone in the desert. If they go on the summer solstice they’ll find quite a few people camping out there and perhaps playing instruments or singing songs. Ultimately it is gratifying – place works in the landscape and then the works become landmarks or sites where people gather at a certain times.

This article first appeared in the September 2012 issue.