In Robert Fisk’s glorious, sad 1990 history of Lebanon at war, Pity the Nation, the veteran journalist traces the turmoil of the Middle East back to the trauma resulting from the Nazi occupation of Europe. In 1986 Fisk went to the Warsaw home of an elderly Jewish Holocaust survivor: ‘On the facing wall were affixed some faded sepia photographs… Each showed a group of schoolteachers sitting on rows of chairs, the first picture labelled 1926, the last 1938, so that by casting our eyes along the row we could see the teachers growing older, the bright, sometimes humorous faces of the Bialystok Gymnasium staff moving inexorably towards the Holocaust.’

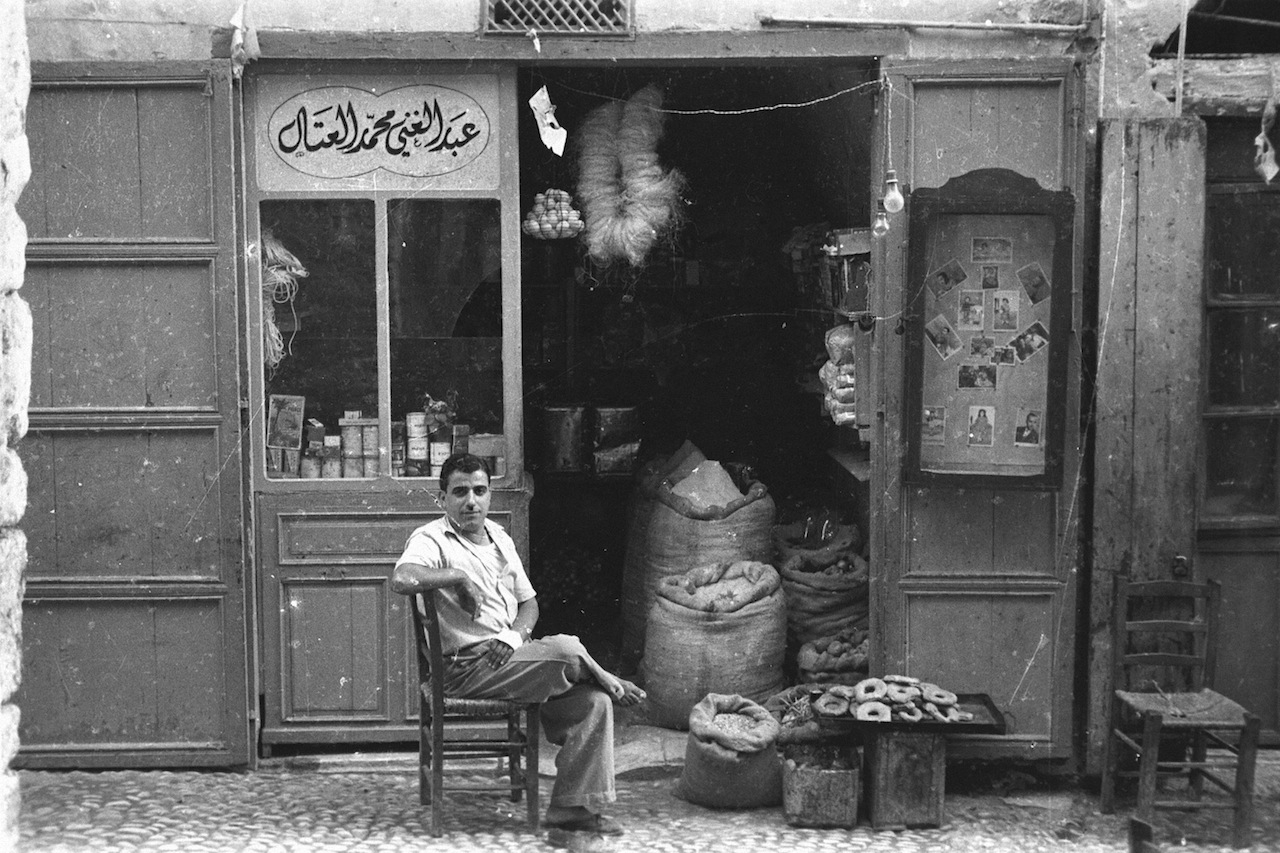

Let us consider another photograph, this time an image that has been used by Akram Zaatari in various iterations of the Lebanese artist’s 2007 work Hashem el Madani: Itinerary. Like those of the Bialystok Gymnasium staff, the photograph is of an ordinary person, but perhaps in this case the subject has the faintest inkling of the fate history has in store for them. It is 1949. Abdel-Ghani el-Attal is outside his grocery shop in Haret el Keshek, in the Lebanese city of Saïda, 40km down the Mediterranean coast from Beirut. Bags of grain lie just outside the shop doorway; a tray of ring-shaped ka’ak bread is balanced on a box. A dozen or so photographs, presumably of family members – children, parents – are pinned haphazardly to a noticeboard. El-Attal is barefoot, sitting on a chair, one leg crossed over the other, an arm resting on the back of the seat. It might be spring, perhaps mid-afternoon – the grocer is wearing a pale short-sleeved shirt over a vest and the scene is bright without shadows. El-Attal stares straight down the camera lens, not at the viewer (in this instance me, standing in Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, looking at a wall of similar photographs of el-Attal’s neighbours in the market of Haret el Keshek) but at the man photographing him, Hashem el Madani. Perhaps both sitter and photographer have realised the impact the first Arab-Israeli war, which had started in May the year prior and ended in a fragile armistice in March 1949, was going to have on their own country and their own lives, perhaps they have not. They must have seen the thousands of Palestinians escaping the Israeli airstrikes – the government in Jerusalem fiercely guarding the land mandated to the Jewish people, friends and relatives perhaps of the schoolteacher Fisk was to meet years later, a territory that was supposed to protect the Jews from more bloodshed. El-Attal and Madani would have been aware of the desperate Palestinians filling the camps in Bourj el-Barajneh and Ain al-Hilweh. Like those refugees, the two Lebanese men may not have realised then that the Palestinians would never be able to return to their homeland, nor would they have been aware of the effect this new population would have on their own country: Lebanon’s precarious democracy about to be destroyed as the country gets sucked into conflict on all sides. In that moment, on that sunny afternoon, as the cogs of history grind on around them, the two men seem oblivious and happy, contentedly absorbed in the job at hand, one posing for the photograph, the other taking it.

Typically for Zaatari the Stockholm exhibition involves found photographic archives, multimedia installations, and film and video, both documentary and fictional (and works that sit somewhere between the two). It complements solo exhibitions at Salt, Istanbul, this year, and the Power Plant, Toronto, in 2014, as well as his participation in the Gwangju Biennale and the Yokohama Triennale, both 2014; and representation of Lebanon at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Zaatari’s work speaks frequently of politics and Lebanon’s fraught modern history, but it has long done so through the telling of individual, personal stories. The people who figure in it – among whom the studio photographer Madani is a major presence – always remain the primary focus, yet he allows the inevitable intrusion of the history they lived through to seep into the narrative. The 10-minute film Red Chewing Gum (2000), for instance, tells the story of the narrator and his lover’s encounter with a chewing-gum seller, noting that gunshots and military skirmishes can be heard in the distance while this small personal drama plays out. The 11-minute Nature Morte (2008), wordless save for the call of the adhān some way off, again evokes the mundanity of conflict in its portrayal of two men working side by side at their respective tasks: the older making a bomb, the younger mending a jacket.

Yet Zaatari’s work is not about researching the past (though that might be part of his methodology in its creation) or looking to write historical, political or biographic narratives. Instead it’s a study of the documents the past bequeaths to the future. So while on a few occasions, especially in those works that involve the Madani archives, Zaatari’s viewer might witness an innate, presumably timeless facet of humanity – the goofing of three friends in an image Zaatari has titled Abu Jalal Dimassy (centre) and Two of His Friends Acting out a Hold-up. Studio Shehrazade, Saïda, Lebanon, 1950s. Hashem el Madani (2007), for example, is so full of the mischievousness of youth that I would happily believe it to have been taken at any point in history – more typically the work highlights the way in which the cultural shifts in the world surrounding these subjects since they were photographed have been too great for us to be able to read them in the manner they might have been read at the time. Take, for example, a series of photographs by Madani in which same-sex couples are pictured in an embrace – one devastatingly handsome boy giving another a kiss, in Tarho and El Masri. Studio Shehrazade, Saïda, Lebanon, 1958. Hashem el Madani (2007), for instance. In Zaatari’s 2004 book Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices, the photographer explains that the subjects aren’t gay couples, but are using the other as substitutes for a heterosexual partner, because it was not seemly for a man and woman to be photographed together outside marriage. While it is not necessarily a revelation that artefacts are read differently as time goes by or cultural contexts change, Zaatari’s work highlights a certain degree of uneasy ambiguity to this process, in which intentions can only be assumed and, with the years rolling by, misunderstanding becomes more likely. In This House (2005) centres on footage filmed by the artist showing the unearthing of a letter written and buried by Ali Hashisho, a Lebanese resistance fighter, in the garden of a house he and his comrades were based in during the late 1980s, together with the conversation of those present at the dig and a new interview with Hashisho (who is now a press photographer of some renown). Addressed to the owners of the house, who at the time the missive was written had been displaced, the 30-minute video documents the letter’s delivery from the past into the present and the consternation this causes the returned homeowner and local authorities who have insisted on attending the exhumation. In a part of the world where history weighs heavily and is frequently used as a pretext for yet more conflict, the wider, wretched political implications of the misinterpretation of historical sources is perhaps self-evident.

The images of el-Attal and his fellow shopkeepers were originally used by Zaatari as part of a walking tour, in which the old photographs were placed in the shops where they were originally taken. At Modern Museet each was mounted, framed and installed in a grid alongside a video of the artist interviewing an older man who remembered many of those featured in the images and reminisced at length about how each shop in the market changed hands over the years. Most of Madani’s work was done not in the streets, however, but in the small, cramped studio he, now in his late eighties, still keeps, on the first floor of a busy street in Saïda. Zaatari’s work Twenty Eight Nights and a Poem (2010–) is a shifting, intimate portrait of the photographer’s work told through a changing multimedia installation, including photographs of items from the cramped studio space; photographs developed from old, often damaged negatives found in the studio; found 16mm film; Super 8 films; HD videos shown on an array of devices including iPads and Kindles; sculpture; and the longest film Zaatari has made to date (also titled Twenty Eight Nights…, dated 2015 and lasting 105 minutes; it is often screened separately). Like much of Zaatari’s moving-image work, in this film Madani’s life is portrayed through an opaque, nonlinear montage of shots taken by the artist. Some of these have a direct link to the subject’s life; others seem more tangential.

Again, the viewer is offered an insight into the personality of Madani and the changing mores of Lebanese society via direct interviews in which, for example, the photographer notes that men only requested to be photographed with guns after 1958 (the year that tensions between Lebanon’s Maronite Christians and Muslims came to a head), or that he was forced to scratch out the negatives of his portraits of a woman, taken before her marriage, after her furious, conservative husband paid him a visit (Zaatari managed to process the damaged images as part of the installation element of Twenty Eight Nights and a Poem). The fact that the interviews are often relayed via various technological means (laptops, smartphones) that Zaatari in turn films provides a clue to the fact that the work is not just about Madani but is also about the media we use to explore history and personal narratives in the present. The film Twenty Eight Nights and a Poem opens with a shot of a laptop sitting on a metal trolley in an archive (the credits confirm the assumption that it is the Arab Image Archive in Beirut, the research centre Zaatari founded with photographers Fouad Elkoury and Samer Mohdad in 1997 and which continues its operations today). The laptop is playing an odd, very dated black-and-white children’s television show, the kind of footage that resurfaces on the Internet, in which a father sings a piano-accompanied song to his young daughter. Throughout the film, occasional intertitles offer definitions of words relating the mediums and source material through which history is relayed, from ‘camera’ to ‘archives’. Likewise, in the final scene Zaatari himself appears (artists also being narrators of history, their work source material for cultural historians), sitting alongside Madani, watching much-loved Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez sing his epic, beautiful lament Ayy Dam’et Huzn La (1974) on Zaatari’s laptop.

This tension between the personal stories of the individuals and the use that the modern viewer has for the images as primary source for a wider historical narrative is one that the artist has long been interested in exploring. In his 2003 film This Day, in which scenes of a pair of hands rifling through old photographs of everyday scenes from the mid-twentieth century in the Middle East are intercut with an array of news reports and Arabic pop songs, there’s a particularly poignant moment. An intertitle, typed across the screen in Arabic, proclaims, in translation, ‘In war, songs change and images transform’. The point being that wars don’t just inflict violence on people in the discrete period they take place, but cast a long shadow, colonising the cultural legacy of a group of people, or the image of a society, way past the moment of armistice, whether intentionally or not.

Zaatari’s primary concern, then, is not war per se, or Lebanese history, or even the individuals that appear in the work, but historiography and how we use media to make sense of our current circumstances. It’s telling that in the artist’s exhibitions, elements from one work are often taken to form another; individual works are used in larger, more immersive installations; titles are repeated; projects take multiple forms; other people’s work is subsumed into his own. In this constant flux, the artist mirrors the shifting narratives that archival documents and primary sources are subjected to and consumed by as generational perspective passes from one to other. Zaatari’s is a body of work that is never didactic but instead presents the things we believe, the stories we tell, as mutable: subject to constant, uncertain adjustment and readjustment.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of ArtReview.