This New York Pavilion of the decentralised biennial functions as ‘a final call’

To call an exhibition a biennial would imply a spectacle, but the latest iteration of the roving Gaza Biennale, installed at the Brooklyn not-for-profit space Recess and titled From Gaza to the World, is a modest affair. In the lobby a monitor plays a documentary featuring profiles of over a dozen of the 53 exhibiting artists, all of whom are from Gaza. Some are currently living under siege, others displaced. Another monitor loops a selection of videoworks by Emad Badwan, Mohanad Al Sayes and Yahya Alsholy. Alsholy’s captivating short film Escape from Farida (2025) cuts between plotlines about a man digging in rubble in search of a kitten, a couple breaking up over whether to leave or stay in Gaza and an aspiring filmmaker and actress attempting to shoot a scene from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (1597) in a dilapidated theatre. Many works on view are reproductions of originals that could not be transported to Brooklyn (the press release calls these reproductions ‘displaced’ forms). Hanging beside the entrance to the main gallery is a textile reproduction of an acrylic painting – presently stuck in Gaza – by Firas Thabet. Titled Gaznica (2025) and replete with references to Picasso’s Guernica (1937) – a mourning woman, an eye-shaped lamp – the one-square-metre tapestry is a proxy for an object that is trapped, alongside the vast majority of the civilian population, inside military infrastructure and red tape in the Israel-occupied region.

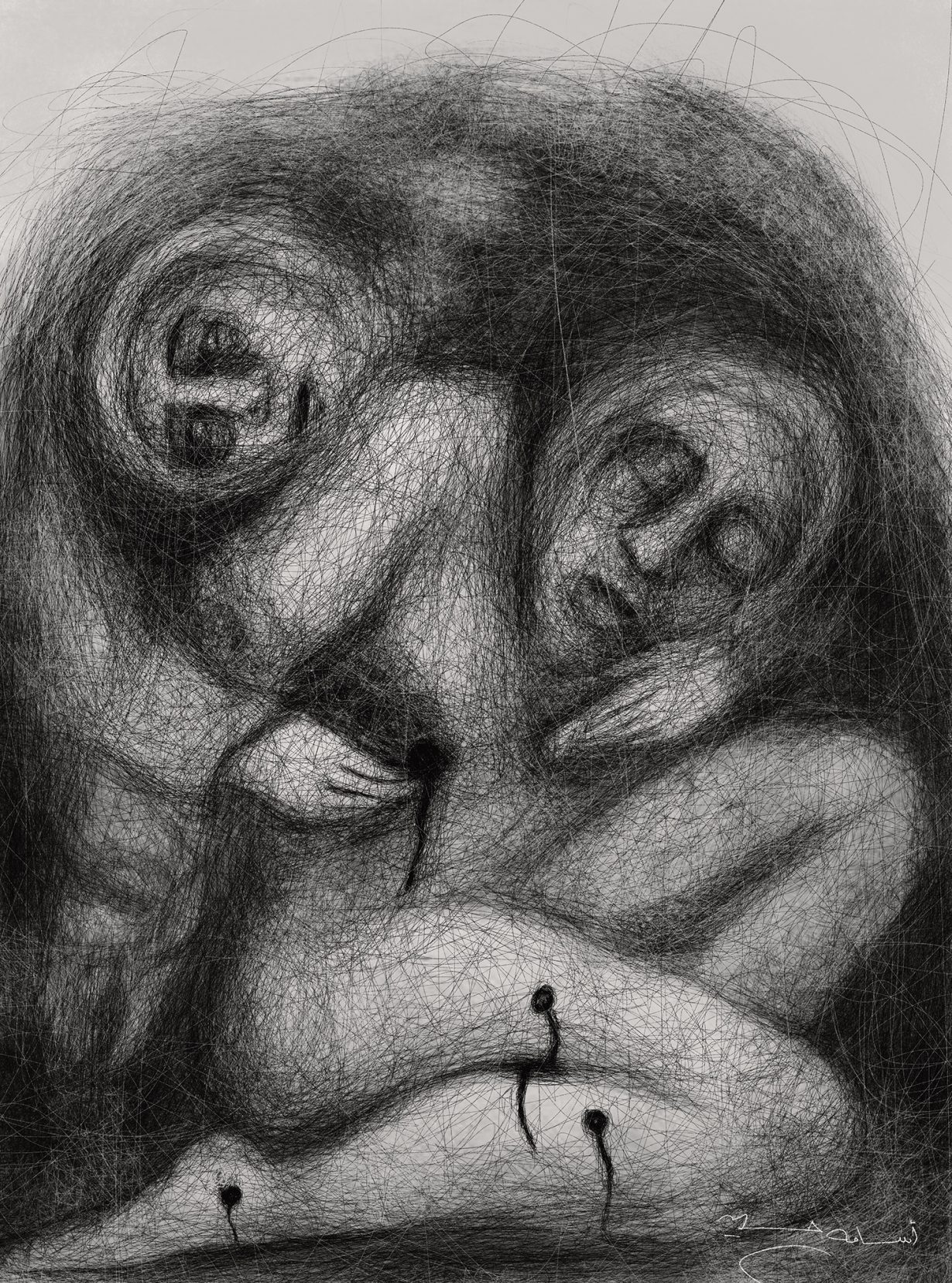

Recess’s main gallery contains mostly figurative two-dimensional works depicting architectural ruins and scenes of destitution, such as Ossama Naqa’s black-and-white digital drawings, which have been printed on paper and hung studio-style on the walls (throughout the exhibition, the works’ original mediums are listed on their labels). One of these drawings, which Naqa made on his phone while sheltering in a garage in Khan Younis, depicts a mourner entangled in a Käthe Kollwitz-esque embrace with the body of a loved one. At the back of the gallery, sectioned off behind a black curtain, two slideshows projected on facing walls advance through photographs of, among other works, gypsum and gauze sculptures by Mohammad Suliman that resemble carefully sorted piles of rubble. Another video, projected down onto a rectangular plinth, shows artist Khaled Huseyin making naturalistic, nearly lifesize clay busts. Here, Suliman’s and Huseyin’s sculptures have no physical form; they exist as transmissions. In the context of the exhibition, they join a host of ongoing signals, from news broadcasts to social media posts, through which Palestinians in Gaza are attempting to convey the horrors of the genocide that the IDF is committing there.

From Gaza to the World is one of 17 branches of an itinerant exhibition curated by Palestine-based artists Fidaa Ataya, Andreas Ibrahim and Tasneem Shatat, in collaboration with the Al Risan Art Museum in the Occupied West Bank. The visuals and ethos of this particular presentation call to mind the notion of ‘bare life’, a phrase coined by philosopher Giorgio Agamben in 1995 to refer to the stripping of life of its civic, legal and cultural dimensions down to mere biological survival. Examples of ‘bare life’, per Agamben, can be found in places where people are subject to indefinite detention by a sovereign power – alive without rights, deprived of the freedom of movement as well as that of permanent settlement. The materiality of the exhibition itself conveys this condition of bare-bones survival: images of works in Gaza are printed on squares of wheatpasted poster on plywood – as is the case with Ahmad Aladawi’s six graphic-style drawings, By Fire by Blood (2024) – and pieces of a vinyl banner, like for Murad Al-Assar’s acrylic paintings The Rose and the War, Palestinian Winter, Pain and Hope and Noise of Death (all 2025). The exhibition design also leans into the aesthetics of provisionality, with plenty of visible eye hooks and temporary structures, such as the black scrim that marks off the screening room, which looks like the threadbare curtain in Escape from Farida against which the aspiring filmmaker and actress film their poison-drinking scene.

Visually, it is undeniable that the reproductions are altered forms of the original works. A Child’s Quest (2025), Mohammed Mghari’s painting of a hunched adolescent pushing acid-yellow water canisters in the seat of a wheelchair, was originally an acrylic painting on canvas. Now it is an image on a waxy stretched surface inside an austere black frame. What was likely a layered and textured surface has been flattened to uniform standard resolution. Same goes for Yara Zuhod’s I Am the Homeland and We Will Return Home (both 2024), two chalk pastel drawings on black paper depicting ghostly, blue-skinned women: one hugs a yellow house; the other holds a large bronze key symbolising the Palestinians’ right to reclaim their land. In the exhibition, these drawings, which were made on coarse A3 paper, have all but quadrupled in size; with each groove in the paper magnified, Zuhod’s images appear to be covered in black specks. While the contents of the works and the events they reference are devastating enough on their own, the artists’ and organisers’ explicit material limitations and the reduced quality of their reproductions also manage to unsettle and communicate, on a subliminal level, the severe reduction of basic living standards to which Palestinians in Gaza have been subjected.

The extent to which the curators could support the exhibiting artists seems also to have been reduced to the bare essentials of a search-and-rescue mission, whose objective was to document and preserve as many works, studios, processes and personal testimonies as possible under the conditions of war. Recess, which proposed to host the biennial by answering an open call, is a small space, and the walls are densely hung. This seems to speak to the organisers’ desire to include as many documents as possible, given that the exhibition is, in the words of participating artist Fatima Ali Abu Owdah, ‘a final call… before the coffins close on all that remains’. By way of its meagreness and provisionality, From Gaza to the World makes a strong case that, for artists living under occupation, art is not a luxury – not a hobby for Sunday painters or a travel souvenir for wealthy collectors – but an imperative and an inalienable record of life and death.

From Gaza to the World at Recess, Brooklyn, 10–14 September