Selected by Alexander Leissle

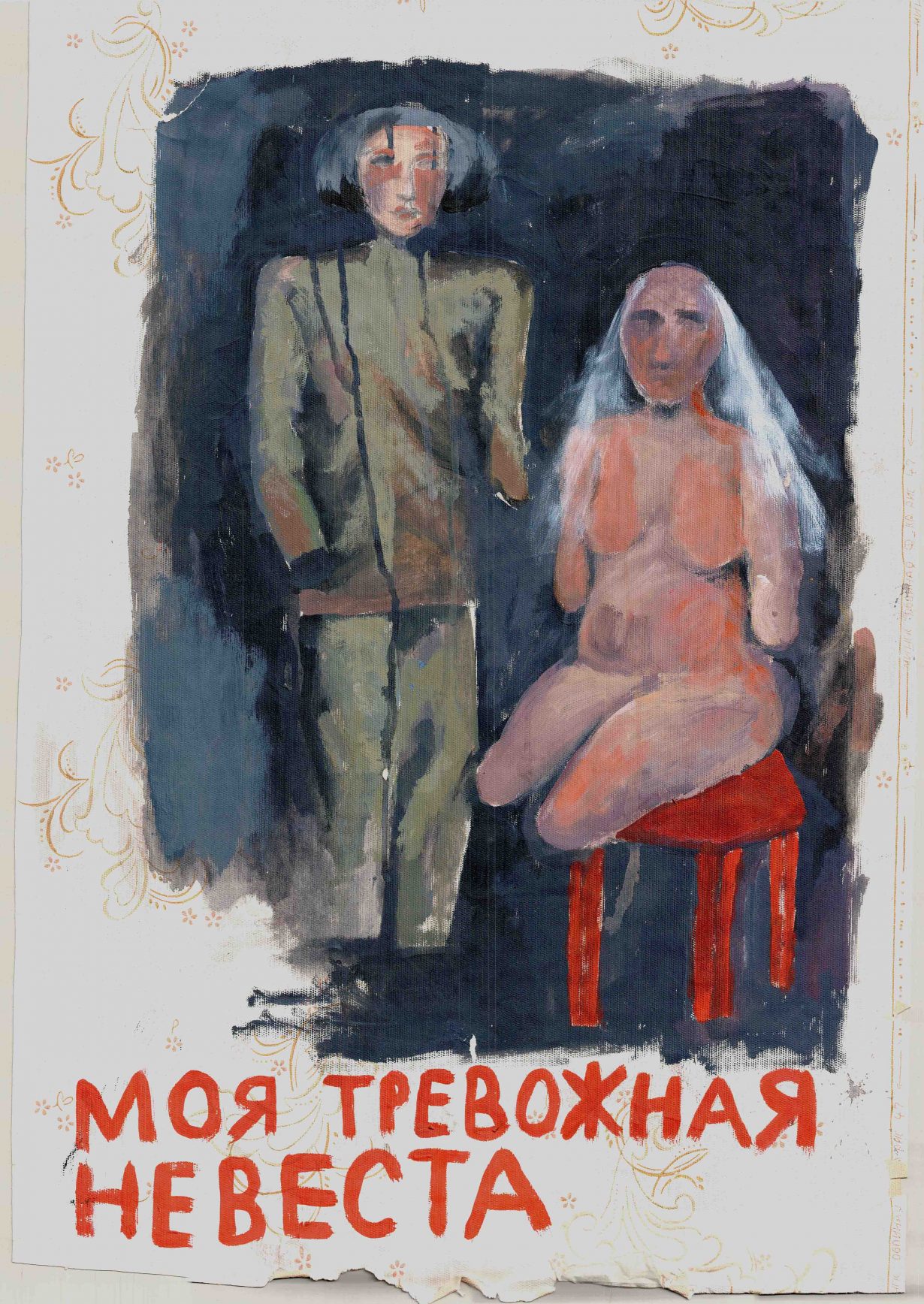

Ukrainian artist Dana Kavelina revitalises traditional animation techniques – puppetry, stop-motion, drawing on paper, masquerade, model sets – in order to consider future technologies. And bodies, war and historical atrocities. Take The Lemberg Machine (2023), a stop-motion animation loosely based on the 1941 Lviv Pogroms. Kavelina built a collection of scale-model sets in which to shoot a series of vignettes that follow a cast of puppet characters. All accompanying dialogue is in Russian or Yiddish (with English subtitles). In one sequence, a woman dives onto a roaring pyre – her body doesn’t ignite, but silently disappears in the dancing flames of frayed orange and red cotton; a German Einsatzgruppen soldier then fires his gun into the air and the dusk backdrop parts, like curtains, to reveal a starry night sky, while other soldiers applaud, whistle, holler. This tug-of-war between plaintive beauty, horror and absurdity is characteristic of Kavelina’s work.

The viewer, too, must know their part, as Kavelina relates the role of the witness to that of the perpetrator: “The camera and the torture chamber took hands and went down one by one,” a narrator cryptically tells us later on in the film; or in another work, Letter to a Turtledove (2020), which combines drawn and painted images with found documentary footage, we can occasionally make out a naked figure looking right at the lens, two eyes staring up through a fractured pane of glass. In Kyiv she opened The Room of Lyolya Yefremova (2020), where she created the living space of a fictional artist who, as indicated by diaries and letters, committed suicide. Only one visitor was allowed in at a time, each for an unlimited duration; waiting, therefore, was part of the experience of the work. Once you got in, the space was all yours to make sense of: artworks, poems, pictures, a laptop, clothes on a railing. How might we, as visitors in this constructed position of voyeuristic power, reflect on the spectacle of suffering? Elsewhere, though, her at-times-bone-dry, tongue-in-cheek humour is refreshing: in a scene from the film There are no monuments to monuments (2021), the artist leans over, hinging at the waist, and props her head between the crotch of a political statue frozen in a victorious wave; “It’s very stony,” a narrator comments in mockumentary style, “perhaps more stony than average.”

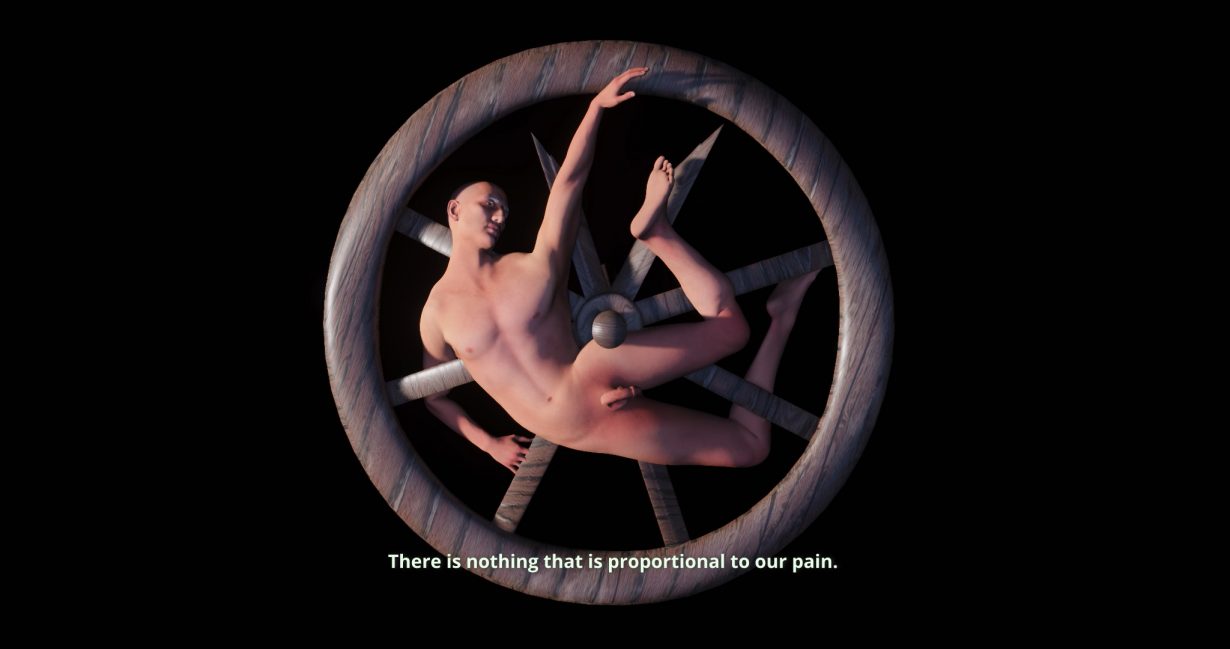

Kavelina’s is a decidedly communal practice, which she elevates in displays of her videowork by presenting photographs, prints and artefacts preserved from the work’s production phase on walls and in glass vitrines. A similar attitude applies to her films, which she will often present, and then later amend, suggesting, along the way, that there is no such thing as a ‘finished’ work. One such ‘unfinished’ work, It can’t be that nothing that can be returned (2022), points to her ambition to carry on working with digitally modelled images. In one scene, an advertisement-style voiceover attempts to sell us on a utopian vision: Ukraine won the war against Russia in 2022; it is now a borderless state defined by its cities and governed by an ai modelled on Soviet cybernetic scientist Victor Glushkov. Liberation here is at once euphoric and disquieting: “trees migrate… the street wants to go outside and become an animal… Sometimes everything suddenly dances.” We explore sites of this strange fantasy: there’s a stack of eyeballs, each individually frozen in glassy cubes, on a factory conveyor belt; militaristic thermal-vision clips – of bugs feeding, pigs asleep in their sty, drone shots of urban society – melt into each other like an overheat- ing film reel. This is the vitality of Kavelina’s work: a tactile, almost spiritual attention paid to the coexistence of ideas, bodies and technologies in a world in which the worst has already happened.

Dana Kavelina works with animation and video, installation, painting and graphics. She graduated from the Department of Graphics at the National Technical University of Ukraine in Kyiv and is now based in Berlin. Her feature film It Can’t Be That Nothing That Can Be Returned (2022) was shown at the BFI London Film Festival in 2023.

Alexander Leissle is assistant digital editor of ArtReview.