The artist-storyteller’s ambiguous installations confront crises in democracy at street level

Gian Maria Tosatti has steadily made a name for himself as a meticulous visual storyteller for the poor, the dispossessed, migrants and third-class citizens. Taking over abandoned or closed-off historic buildings in the neglected neighbourhoods of mostly European cities, the Rome-born artist creates poignant installations that are rarely advertised openly as exhibitions; they are there for anyone to stumble upon. “I have to make art in the city, where people live,” he says when we talk in Istanbul. “I’m not doing it for the king or his court, I do it for people who need it. When I go to these neighbourhoods, it’s not because I have something to tell them. I’m just a translator, not an author.” Despite working in rough environs, the time and dedication he invests in the people and spaces pays off – his shows often become word-of-mouth success stories, attracting a variety of people. “I’ve worked in the hardest part of Naples and in refugee camps. Those are not places where if you do some kind of bullshit thing they tolerate it, because they have real issues. They don’t have time to waste with your… you know… vanitas.”

In 2018 Tosatti returned to Europe after ten years in New York. “I felt too alien there. I wanted to come back to my land, my history, with all the problems Europe was facing,” he explains. In Italy, Matteo Salvini, the far-right Lega leader, had rapidly risen through the ranks, becoming deputy prime minister that same year and infamously closing Italy’s ports, effectively banning a number of migrant ships coming onto Italy’s shores. Europe’s postcolonial heritage and its inability to renegotiate relations with its old colonies was a trigger for

Tosatti’s ongoing pilgrimage My Heart is a Void, the Void is a Mirror, an in-depth and long-term investigation into the crisis of democracy in the West articulated as episodes across a number of cities.

The latest takes place in Istanbul, in Tarlabaşı, a low-income, predominantly Kurdish neighbourhood established during the nineteenth century on the northwest corner of Istanbul’s famous Taksim Square, a stone’s throw from what’s now the glitzy İstiklal Caddesi shopping hub. Tarlabaşı and İstiklal Caddesi are separated by a six-lane boulevard built during the 1980s, a physical barrier that ultimately contributed to the neighbourhood’s ghettoisation. Filled with dilapidated buildings and dirt-paved roads, Tarlabaşı is treated like a slum by absentee landlords. Still, cheap rent and proximity to the city centre have made it a haven for migrant workers coming from impoverished southeast Turkey, as well as, more recently, Syrian refugees, a burgeoning transgender community and Roma/Gypsy groups. It is a thriving, culturally diverse area filled with shops, markets and people – children especially. Its location also means it is composed of potentially prime revenue-generating real estate, and consequently the neighbourhood has found itself swept up in the government’s ambitious urban regeneration strategy, which since 2006 has principally targeted informal housing areas and historical city centres, along with former industrial estates and disused harbours.

As part of this, a 20,000sqm section of Tarlabaşı that includes 210 historic Ottoman-era buildings has been earmarked for regeneration by the local municipality and the Housing Development Administration of Istanbul, known by the Turkish acronym TOKI. When Tosatti first came to Istanbul, in 2015, following an invitation (eventually declined) to participate in the city’s biennale, he stumbled across the neighbourhood and was struck by a massive construction site, made up of what he calls ‘channels’ all around the neighbourhood. “They were 20m deep. I was very shocked to see an entire neighbourhood surrounded by this abyss.” When I visited Tarlabaşı in early July, the construction site had given way to Taksim 360: a soulless, sprawling complex in a faux art-nouveau style that markets itself as ‘the exclusive lifestyle you’ve always dreamed of’. The buildings stand largely empty, a casualty of the country’s lingering currency and debt crisis.

For Tosatti, the neighbourhood was a prime example of democracy failing those who needed it most. It was the all-too-common story seen in big cities around the world: eviction dressed up as gentrification, entire communities uprooted and erased. Except here it was turbocharged by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s top-down, frenzied infrastructure investment of over $150bn to modernise the country and turn Istanbul, which generates 30 percent of the country’s GDP, into a global financial capital. Every time Tosatti returned to Tarlabaşı, he found more construction sites. Over six years, the artist, often operating a mechanical merry-go-round to provide the younger members of the community with an opportunity for leisure activity, gradually made friends with the locals and their children. One day he saw a young deaf girl walking with her friends. She became the inspiration for the performance at the heart of the Istanbul episode.

Located in a run-down art nouveau building on one of the main roads of Tarlabaşı, the immersive installation – produced in collaboration with Italian nonprofit The Blank Contemporary – takes over the whole venue, which took a total of two months to prep and clean. “We had a volunteer assistant join us and she left after a couple of weeks because she said it was such boring work,” Tosatti says. Visitors are allowed one at a time; I await my turn, knowing little, beyond that there is a performance element, about what to expect.

Entering the tall, narrow building feels like passing through some Lynchian portal into another time, another dimension. The marble stairs look as if they could crumble; the stucco is peeling; in an alcove by the stairs there’s a dish of food for the local cat, an informal character in the show. I climb to the first floor, half expecting the performer to jump out at me.

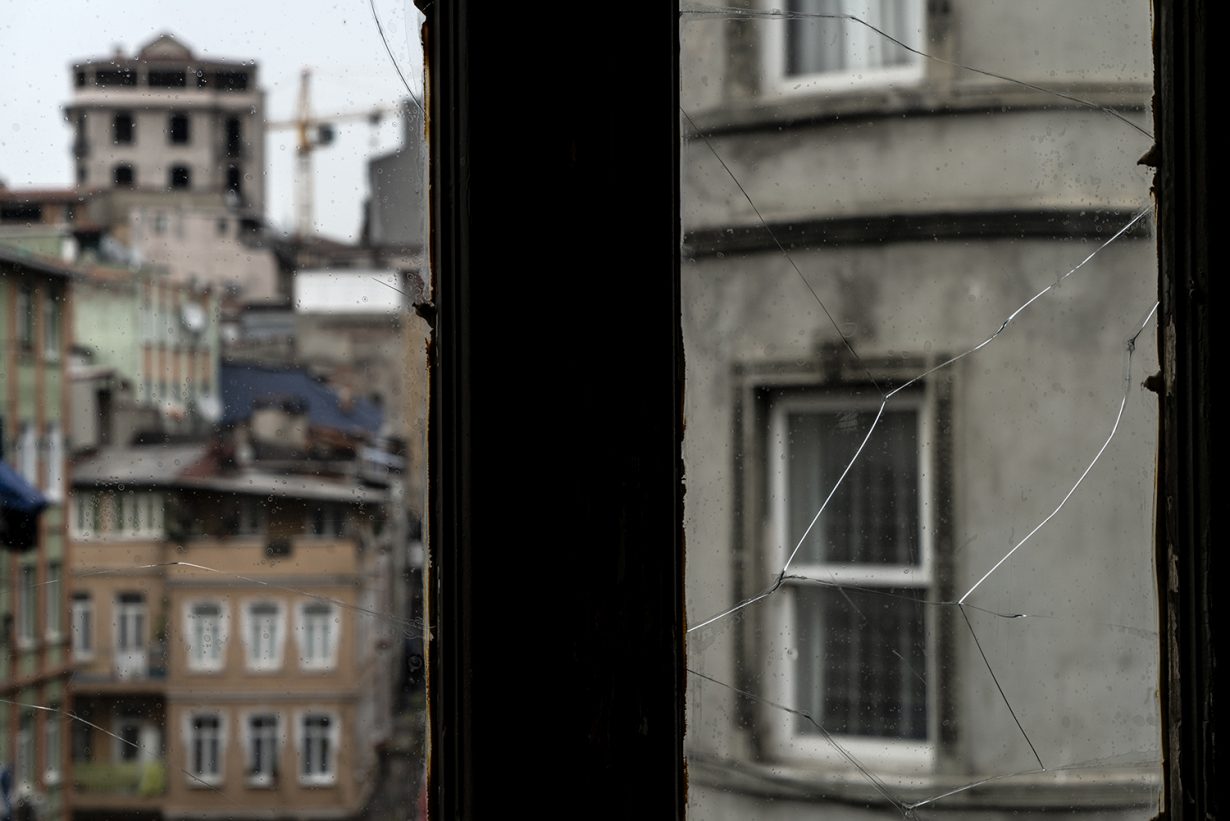

This level comprises several interconnected rooms, sunlight beaming through large windows. In the centre of one room, a performer sits on a chair, head resting on an oval wooden dining table. A crystal chandelier hangs above her. She is small, like a child, dressed in black and surrounded by disquieting signs of a past life frozen in time. All the glass, including the windowpanes, is cracked. An ornate pendulum clock swings rhythmically, its hands absent. I notice the girl leaving from the corner of my eye and pursue her in a panicked fashion – it feels like following her will clarify my route. She ascends to the second floor and approaches a gramophone; a beautiful, crackling recording of a melancholy opera floods the room. I later learn this is the voice of tenor Richard Crooks, from a 1930s recording, singing the aria Mi par d’udir ancora from Georges Bizet’s 1863 opera I pescatori de perle. The girl turns the gramophone towards an open window, drowning out the sounds outside and offering some respite from the pervasive soundtrack of demolition. She stares out at the transforming locale before slowly leaving. I try to find her, to no avail. It feels eerie again, like the place is haunted and I’m looking for a spirit. Carefully laid out details feel like clues to a puzzle: a snowglobe with no city in it, a blanket over a damask couch, books including a Turkish version of James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914), Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar’s The Time Regulation Institute (1962) and Orhan Pamuk’s Snow (2002). On the top floor, I step gingerly onto a balcony girdling the entire building. Outside is the vertical modern skyline of Istanbul, and just below, the neighbourhood being slowly but surely swallowed up in the name of urban renewal. Finally, in a closed-off space with glass windows, what looks like snow covers the floors of the rooms beyond.

“I wanted to speak about this heroic girl who was fighting with music against the cranes, against all these aggressive sounds which speak of destruction,” Tosatti clarifies later. “She wants to calm this Moloch coming to destroy her world, her house. This snow was stuck in my head. It came from my memories of the last story in Dubliners, where it’s the symbol of the dead. Then I started to think this place is not a battlefield, this place is gone. It’s not a dying star, it’s a dead star, but we are here just watching the light that remains. Then I told my assistant, maybe the girl’s not a hero, maybe she’s a ghost, and a few hours later, the wife of the café owner arrived with these pictures of her dead daughter who had died in that building. I said, ‘Damn, it’s the ghost that we were talking about’. The day after, at the very end of March, it snowed so much in Istanbul – the snowflakes were so enormous. It hadn’t happened in years.” Tosatti’s poetic homage to a dying community is moving in ways that only the best kind of art is. We cannot help but watch the fading light and think about all the means by which people, in Istanbul and beyond, can be erased or forcibly disappeared, left without a place or a story of their own. In this context, Tosatti’s work, and his strategy of displaying it within and as a part of the reality that inspired it, will at least ensure that one such place and one such story is treasured.

Ana Vukadin is a writer based in Italy