At Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon, 19 artists – from Max Ernst to Monira Al Qadiri – inject a mixed sense of geophysical precarity and wonder into the viewer’s veins

Sometimes it can feel more impressive to see a familiar rubric redesigned than an unfamiliar one offered up, and Sun Rise/Sun Set is such an occasion. I can’t remember when I first saw an exhibition concerned with humanity’s tricky relationship to the natural world, but it’s a couple of decades ago at least; and I saw many others between then and this 19-artist colloquy, which weaves together works by figures as diverse as Max Ernst, Monira Al Qadiri and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto in what amounts less to an intellectual curatorial argument concerning how we live on this fragile planet than to something bodily, kinaesthetic. The show, in its leftfield juxtapositions, glancing interplays and near-theatrical scenography – which extends into a catacomb of annexes and corridors – all but injects a mixed sense of geophysical precarity, wonder and inexorable cycles into the viewer’s veins.

The tenor is established upfront, in the first of several darkened, softly spotlit rooms. We’re both confronted with Henri Rousseau’s gorgeously faded 1908 painting of animalistic ravishment, La belle et la bête, and invited to look through it – since for atmospheric reasons it’s suspended in a vitrine – at Pamela Rosenkranz’s huge, conical indoor earthwork Infection (Calvin Klein Obsession for Men) (2021), its peak glowing green via concentrated coloured lighting. The Swiss artist has impregnated several cubic metres of rich primordial compost, containing everything from charcoal to human faeces to animal bones, with the eponymous designer perfume – which, in turn, contains artificial cat pheromones. All this loops back to Rosenkranz’s interest in toxoplasmosis, which cats gift to swathes of humanity: if you like this mound’s aroma, a cat may have given you a neuroparasite. Our relation to nature, we’re reminded, is a complex and sometimes gnarly symbiosis.

Meanwhile, off to one side of this black-and-green hill, Pierre Huyghe’s Cerro Indio Muerto, a 2016 photograph of a human skeleton he found in the Atacama Desert, gives the lie to mortal mastery of the planet, parts of which are uninhabitable – all we can do there is rot back into the land – and the aforementioned Sakamoto’s reverberant sound installation Zure (2017), a grand piano that survived the 2011 Japanese tsunami retrofitted to ‘play’ seismic data collected worldwide, underlines the tenuousness of our grip on this big floating marble. These parts address each other but don’t quite fit together, rather fibrously entangle, as you try to navigate unresolved oppositions: rich loamy scents and death, painterly beauty and violence – what is beauty and what is beast?

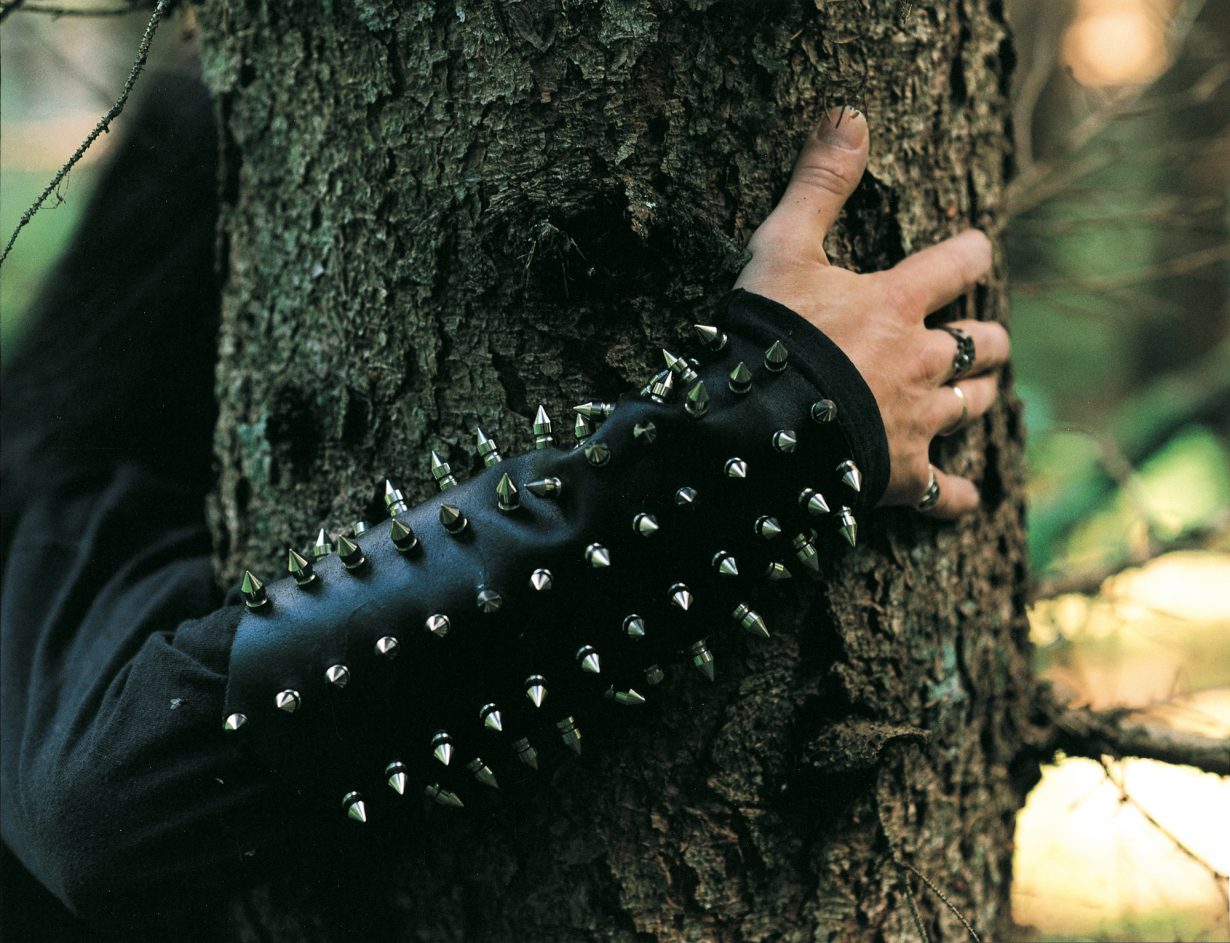

In the next room Huyghe reappears, his Circadian Dilemma (Dia del Ojo) (2017) comprising an aquarium of blind, translucent cave fish that darkens and lightens according to the atmosphere outdoors. A Torbjørn Rødland photograph, Frost no. 4 (2001), from his well-known sequence of images featuring black-metallers hanging out in Norwegian woodland, offers a parallel equipoise of dark and light, with modern musical subculture turning out to have much in common with Caspar David Friedrich’s nature worship. Across the room, tightly lit in the gloaming, an Emma Kunz crayon work, Work No. 25 – undated, but after the Swiss artist/healer started making geometric drawings using a pendulum, during the late 1930s – covertly attests to yet another kind of cycling: the artworld’s own, given that Kunz’s work is fashionable again, as are spiritually minded art and, indeed, the kind of plant- based holistic medicine the artist favoured.

That fact transitions us neatly towards a suite of Karl Blossfeldt’s vintage, still-sparkling architectonic photogravures of plant life; a small, antibucolic painterly nocturne by Anj Smith featuring creatures caught in a diaphanous web (Nächträglichkeit, 2010); and the bleeding-edge science of Neri Oxman’s grid of test tubes, Melanin Library (2020), reflecting research into incorporating human skin pigment in architecture in order to – don’t ask me how – perform tasks such as recycling and energy production. The latter is one of several pivot points in the show where matters move into a major key – from sunset to sunrise, if you will – tracking the progress of scientific knowledge, what might be possible if we act inventively before one large force or other wipes us out. It’s quickly and neatly followed by indigenous Australian group Karrabing Film Collective’s hallucinatory postapocalyptic film Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (2018), set in a future Northern Territories where climate change has rendered it impossible for people lacking melatonin – ie whites – to go outdoors.

Looking for a bridge between human and nonhuman perspectives, the show’s curators close out with a one-two of works themed around octopi, some of the smartest organisms on the planet. Monica Al Qadiri’s Divine Memory (2019) digitally merges footage of cavorting eight-legged beings with hot pink distortion, Islamic poetry and videogame bloops, as if seeking a language to cut across cultures, generations and species. And venerated French underwater filmmaker Jean Painlevé’s The Love Life of the Octopus (1967), not unlike last year’s Netflix film My Octopus Teacher, is a creature feature that dwells on its nest-building, its cascades of eggs. Octopi, with their three hearts and with brains situated all over their bodies, ought to feel alien to us and in some ways they do – but their intelligence and tenacity might also have an affective appeal, make us alien cousins, albeit ones now menaced by climate change and oceanic pollution. If they need us to stop despoiling their habitats, we might need them as a way of personifying and even intellectualising the natural. The last thing you see in the show, accordingly, is a long-dead mollusc, making surreal curtains of eggs in its nest, labouring to ensure the survival of the next generation. It tugs, with eight legs, at the heart.

Sun Rise/Sun Set is on view at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, 26 February – 25 July