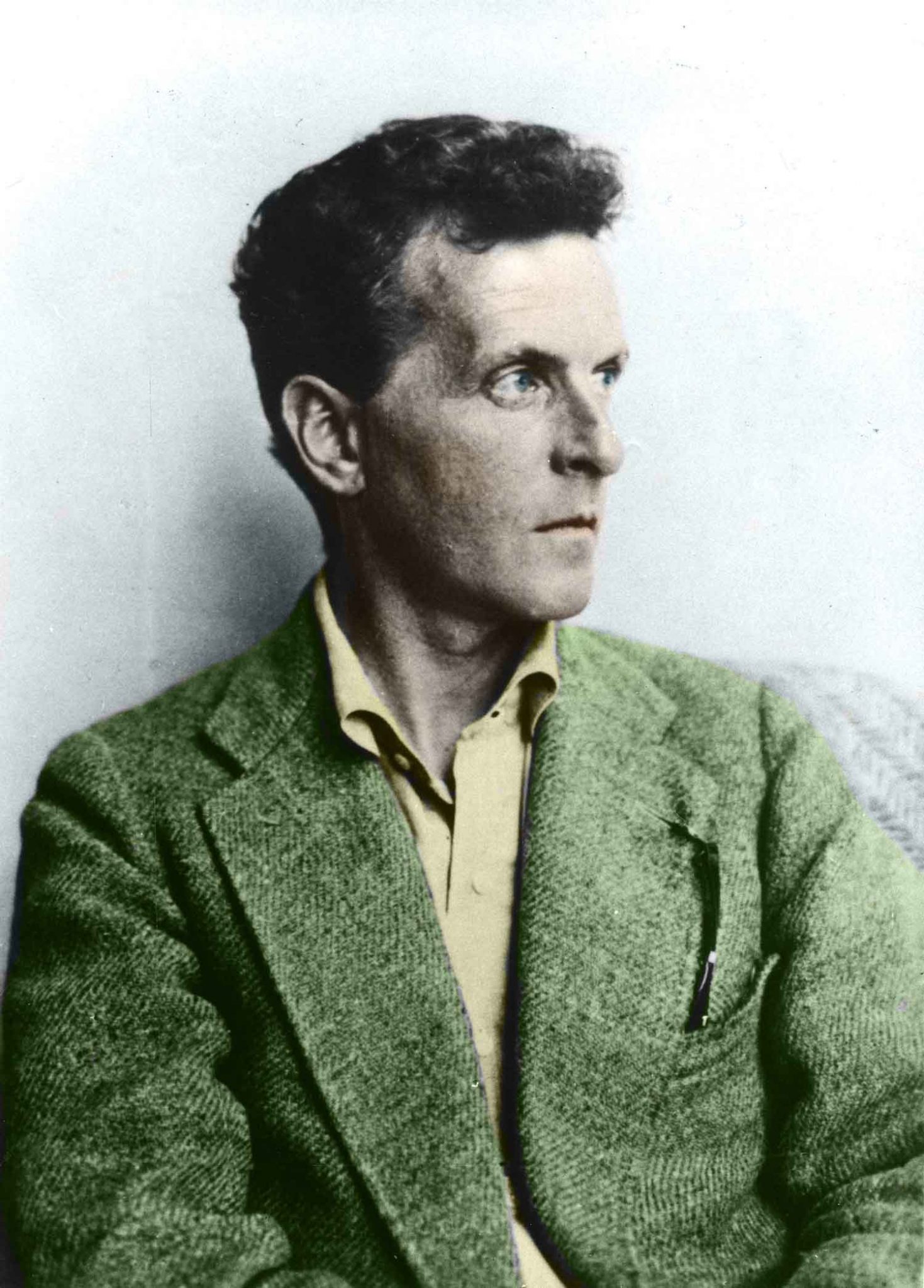

Ludwig Wittgenstein was an Austrian-British philosopher, specialising in logic, mathematics, the mind and language. He died in Cambridge in 1951. His ideas had a profound impact on art appreciation and artmaking during the 1960s and 70s, particularly in the transition from an object-based practice to a concept-based one.

ARTREVIEW

Why was there such a buzz around your name among artists 40 years ago?

LUDWIG WITTGENTSEIN

I suppose it was the time of Jasper Johns, and then Joseph Kosuth finding Johns impressive. And it was because of the idea of art as language, or of there being some connection between the two. With Johns it’s the mismatch between image and word, and then an awareness of a dimension of painting, which might have been thought of as ineffable immediately before that point, suddenly becoming strangely different: brush strokes possessing their own lively independence from description or depiction become almost more logical, readable and nameable than supposedly simple images or basic words. But they are all separated out and at the same time fused together, so a new model of ‘the world’ and how we ‘are’ in it, is offered. I wrote about painting when I was alive, but not like that, and not very much. (As you know, I wrote very little.) It’s more that my ideas were applied to art when art became something to be analysed by artists. I didn’t demand that they do that. I said that it is through the various languages that we are constantly speaking that we create our life world. And then between the mid 1960s and mid 70s, there was a radical change in the orientation of Anglo-American analytic aesthetics, whereby an ahistorical, psychologistic analysis of art and its appreciation was replaced by a historically contextualised, sociological account. This was made possible in part, even if to some extent it was a reaction against them, by my researches into meaning. And in that same period there came a point where you might see a clock on the wall, a photo of the same clock next to it, and then a dictionary definition of a clock, and this would be Kosuth in an art gallery, and it would be natural to interpret what you saw as something to do with me. Pretty heavy stuff: I mean, forceful in the sense that an art scene was completely won over, at least on the fashion level. You had to know my name.

Are you influential now?

LW In philosophy of mind I am important, but no longer in aesthetics and art production. I wrote down some reflections on the problem of choice, for example, and some of these were referred to by later philosophers attempting to explain new cultural developments. The idea emerges that the artwork serves as the embodiment of a multitude of choices made on the part of its author. The choice in John Cage’s stuff, for example, is the choice to make no choices. But ‘choices’ today has different associations. I think of Grayson Perry. He’s making a choice about identity on a personal level, and then other choices about other levels: the level of making, for example ¬ he’s going to make pots and not get a factory to make them for him. It’s a gesture against impersonal making in art, and it’s real, he really is personally making something. These choices are going on in a society where choice has become sinister, because it’s often an illusion. Thoughtful analysers of post-Fordism demonstrate that we’re self-subjugating or self-exploiting when we think we’re free, or in those moments when we believe we’ve made choices about ‘the self’ but we’ve really only made certain moves within consumerism, which are not really choices at all.

Do you think Perry is serious?

LW It’s an interesting question. It’s certainly the immediate difference between him and Kosuth: one thinks of Kosuth’s essay ‘Art After Philosophy’ (1969) as very serious, whereas Perry is a symbol of the fun that art now offers to a completely mass audience. Perhaps neither is quite true of course. I wonder what Perry is really serious about most? It must be difficult encountering him at an art event when he is dressed up as a woman. You are forced to act artificially. But then you have only become more aware than usual that all interactions at such events are highly artificial anyway. They’re group rituals. But in this case it’s one particular person’s excessive artificiality that dominates. Perhaps he is most serious when he is making aesthetic proposals, that is, when he’s making things – at least if you measure this kind of seriousness by originality and surprise. It’s more a shock rather than an aesthetic experience, exactly, when you are forced, as a man, to respond without embarrassment to another man wearing a dress and make-up in a social situation (if you are not in drag yourself). But if you’re asked to consider some shapes on a pot, and the shape of the pot itself, or some embroidered shapes, and depictions and words that the embroidery and the pot each support, then shock isn’t the word. But this large public for whom he is a positive symbol of progress, is in fact encouraged to think of shock in both cases.

Who encourages them?

LW His PR people, the system of art today, and the greater force that shapes this system for its profit-making ends. You could say he does too. Or you could see the aesthetic experience he offers with his pots as resistance against that greater force. You can see the shock therapy he engages in with his dress wearing as resistance as well. But they are really different types of resistance. You know, of course, that I financially supported great artists such as the poet Rilke, the painter Kokoschka, and the architect Adolph Loos; I am responsive to the arts. And I think the best thing about Perry, as with great figures of the past, though not necessarily on their level (after all, posterity hasn’t made its judgment yet) is that he works in a way that’s quite free and fresh. And he plays the game of kitsch – with his adolescent drawing style, in particular, but also with his faux naive narratives – in a way that still takes the other materials he’s working with very seriously.

And Kosuth?

LW You mean what is the best thing? To answer that I think I would choose to think about the distance in time between now and the 1970s. And I would imagine in an ahistorical way someone thinking of him, in retrospect, as one of the quintessential conceptual artists. I’m also thinking of the description I just gave of that work featuring the clock with its different iterations. Now, you might think of Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe, but you wouldn’t necessarily have predicted in Magritte’s time that such a proposal in the form of a self-questioning painting, would ever take the form of Kosuth’s definitions series. So once again I am exhilarated by the aesthetic surprise.

What about institutional critique? Do you think this is an important tendency in art now, is it legitimate, does it have anything to do with what you’re saying about surprise?

LW Indeed it does. You have to adjust to a certain level of aesthetic horribleness in some cases, but in others you’re dealing with something more refined, maybe not possessing much observable expression of feeling – much affect, that is.

You are very highly strung. Do you think art is better when it’s passionate?

LW I like the political philosopher Chantal Mouffe’s idea, that passions should be part of democracy, and politics should be all about finding a way for passionate differences to come out, rather than creating a false impression that they have been removed, or must be removed, which is only repression, and often leads to an explosion of much more horrible and violent political passions. We see that in the various returns of fascism and right-wing popularism as the even more grotesque response to neoliberalism’s relentless dominance. But in an aesthetic context I think passion is a misleading word. Perhaps a more helpful issue is the difference between scientific and aesthetic proposals. Aesthetic experience and aesthetic appreciation – this is a pretty gripping area. I confessed in one of my journals, once, in 1947, that I don’t really care if scientific problems are solved, but aesthetic ones, yes. What aesthetics does is to make you see. That’s all philosophy does. With aesthetics, you go from a description to further descriptions. You make someone see what music by a certain composer is doing, by drawing attention to other music by the same composer, or comparing it with literature the person knows. You make them see what you see, by placing things side by side. You make unease disappear.

What do you think an artist needs in order to get anything done?

LW Confidence I guess, like anyone doing anything. Belief. But they are elusive, and then when you get them, to a certain degree, enough to start being creative, you never know what the fall-out will be. I come from a wealthy family that lived in an extremely grand house, and financially supported the greatest artists of the period. Some of my brothers committed suicide. They all ran away. One just disappeared. Another went into a bar in New York, ordered a drink, swallowed it, and then took out a gun and shot himself. Maybe I would have done something like it. At a young age I became morbidly obsessed with justifying my existence, but instead of leading to suicide it led to an interest in philosophy. It led to Bertrand Russell. He was the great man then. He was generous, he allowed me in, he was full of confidence, and he built up my philosophical confidence, my powers of rational questioning. But then I was so confident I questioned his confidence, and my confidence actually started to break his down. He couldn’t write the books he wanted to write any more, because I undermined the ideas he was expecting to elucidate in them. He couldn’t believe in them.