Three African artists take on gender, identity and online culture at QUAD, Derby

Africa is often seen as a homogenised, monocultural continent, but each striking body of work in this exhibition deals with complex socio-political issues and defies such simplifications. The show comprises work by three artists selected by open-call – South Africans Anthony Bila and Sipho Gongxeka and the Nigerian Uzoma Chidumaga Orji.

Entering QUAD, it’s hard to miss the large format, portrait photographs from Gongxeka’s series House of Realness (2018). Hung on two flights of stairways, Gongxeka’s confident subjects display an unconventional glamour, wearing statement pieces – patterned shirts, a tartan skirt, Doc Martens and bucket hats. They pose with a degree of openness, looking directly at the camera, but the physical distance between them and the lens makes us question what they are holding back. The empty streets behind the subjects and the photographs of cars and abandoned places, are a stark reminder of slowness too. Scenes of twisted, flowing plant stalks, overgrown greenery and quiet concrete landscapes show what environments might look like if left untended. Sunlight and shadows stand out as black queer identities are brought to the surface, radiating against the derelict scenes. The story behind the faces hints at a bittersweet queer culture in South Africa, a country with some of the most progressive LGBTQI+ laws in the world, yet where this community still faces prejudice and violence because of their sexual or gender identity.

2 images

In between the first and second flight of stairs showing Gongxeka’s work is a landing with Bila’s the power(lessness) of (n)one (2021) – three sets of three, wall-mounted, black and white photographs. Imposing brown industrial ropes drape above the photographs from the corners of each wall, falling down the sides – their weight collapsed into a small pile on the floor. Bila captures all three subjects alone against the background of dishevelled yet peaceful developed areas; it is the perfect antidote to their intense yet effortlessly poignant expressions. The same ropes that hang in the room appear in the photographs . Sometimes, they are tied tightly around different parts of the subjects’ bodies. Other photographs show the ropes hung or looped loosely around shoulders, or woven through hands lifted to the sky. The photographs harnesses different ideas of what it means to be – free or contained, conformist or individualistic, present or absent. The ropes, too, feel like a symbol of the emotion the work carries – heavy: a common feeling, but also one that to be found in the emotional reaction to recent lockdown restrictions, a situation the artist grappled with whilst making this work.

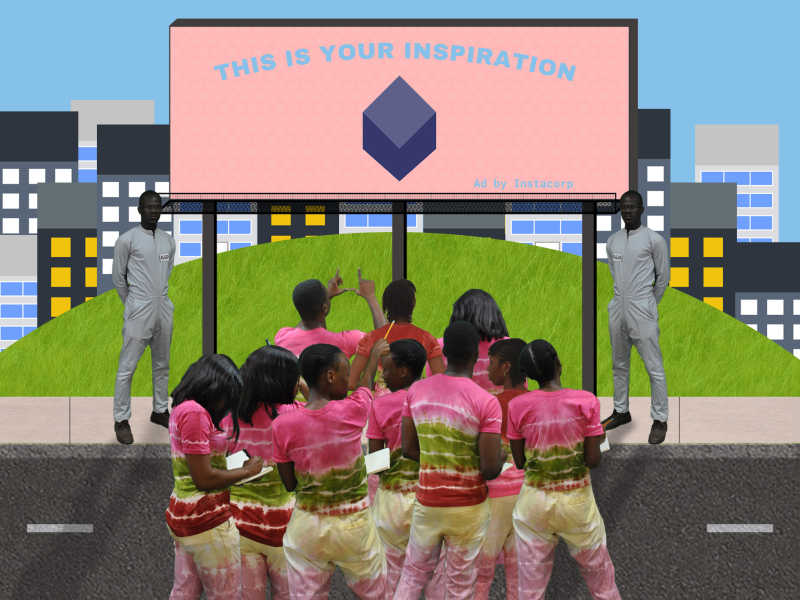

Arranged across the floor of an adjoining foyer space, pink lines or wires on the floor turn inwards, stopping at Orji’s piece Welcome to Instaland (2021). Like an 8-bit computer game or a child’s play-town matt, boldly coloured, blocky-shaped roads, buildings and green spaces draw us into a flat, printed space which covers most of the floor area. Like online reality, there are many layers to the work. Humorous texts accompany the images: ‘Here we have our most exclusive bar/restaurant, The Clout, the watering hole of our city’s who’s who. Common riffraff need not bother, it takes lots and lots of clout just to get in the door’. Pink wires bend up from the edges of the artwork on the floor to three walls with further images: computer-generated scenes of Instaland with photographs of people dressed in identical bright tie-dye outfits – they are the ‘artists’ of Instaland. While in some photographs the artists are seen scrambling to make the best (albeit identical) artwork, in other images they line-up these artworks to be judged by the city’s ‘Clout Conferment Committee’. Unlike the other pieces, Instaland is about wanting acceptance; demonstrating how vulnerable artists and others have become to hidden algorithms, echo chambers and the detrimental effects of social media.

These three artists offer reflections on individualism contrasted with communities that can be virtual, emotional or physical; communities which are moving away from traditional forms of community in African culture that stem from family, tribe and religion.

Here, There and Everywhere is at QUAD, Derby, 17 May – 5 September

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here