How does one live in the wake of cultural devastation? The artist – who will represent Singapore at the 59th Venice Biennale – is building her own library of conscience

There’s a famous line from Heinrich Heine’s otherwise not particularly well known 1823 play Almansor: A Tragedy that goes, ‘Wherever they burn books they will also, in the end, burn human beings’. We all know what happened in Berlin 110 years later (the Jewish poet’s works were particularly abhorred by the Nazis), and then even later, during the Second World War. Heine’s chilling observation – that cultural censorship inevitably leads to actual genocide – is more complex in reality, as the relationship between the different forms of violence can be blurred and indistinct. But his line of thought has been generative for Shubigi Rao. The India-born, Singapore-based artist has made it her mission to trace a history of book burning, destruction and banishment, with the broader goal of exploring the cruelties human beings inflict on each other.

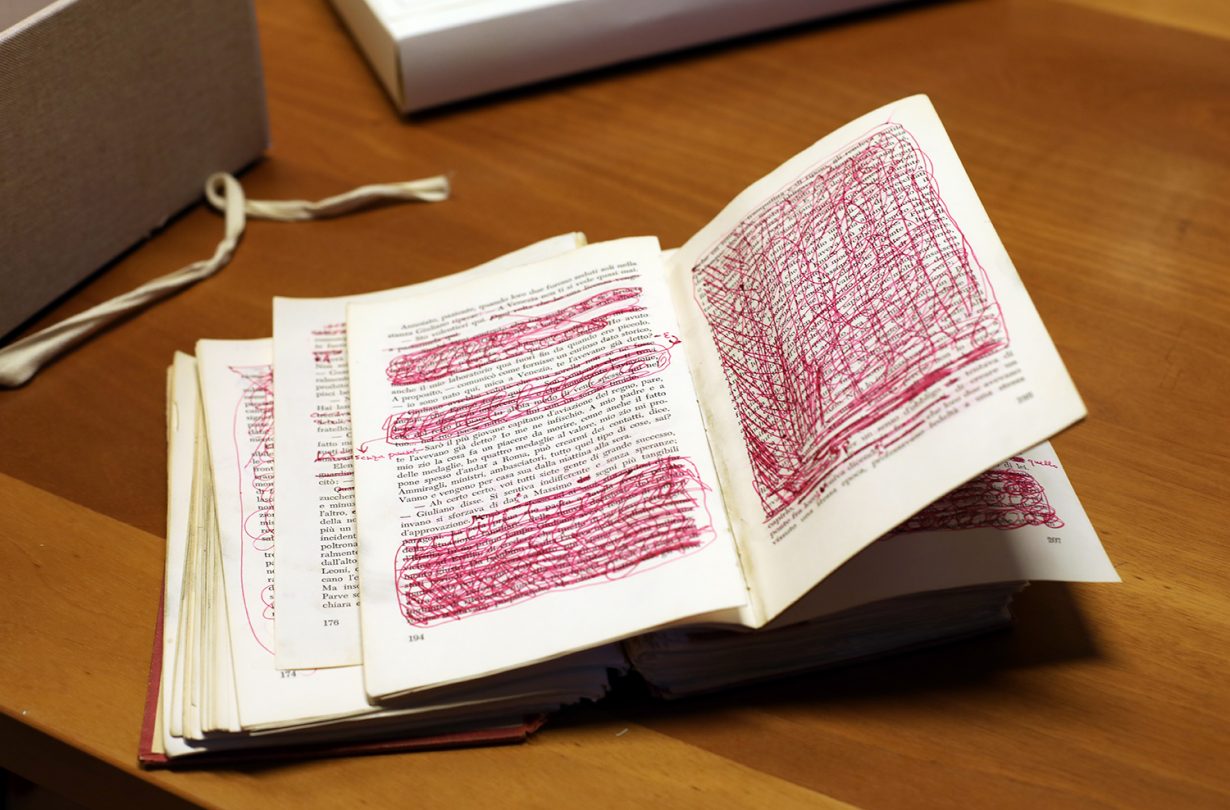

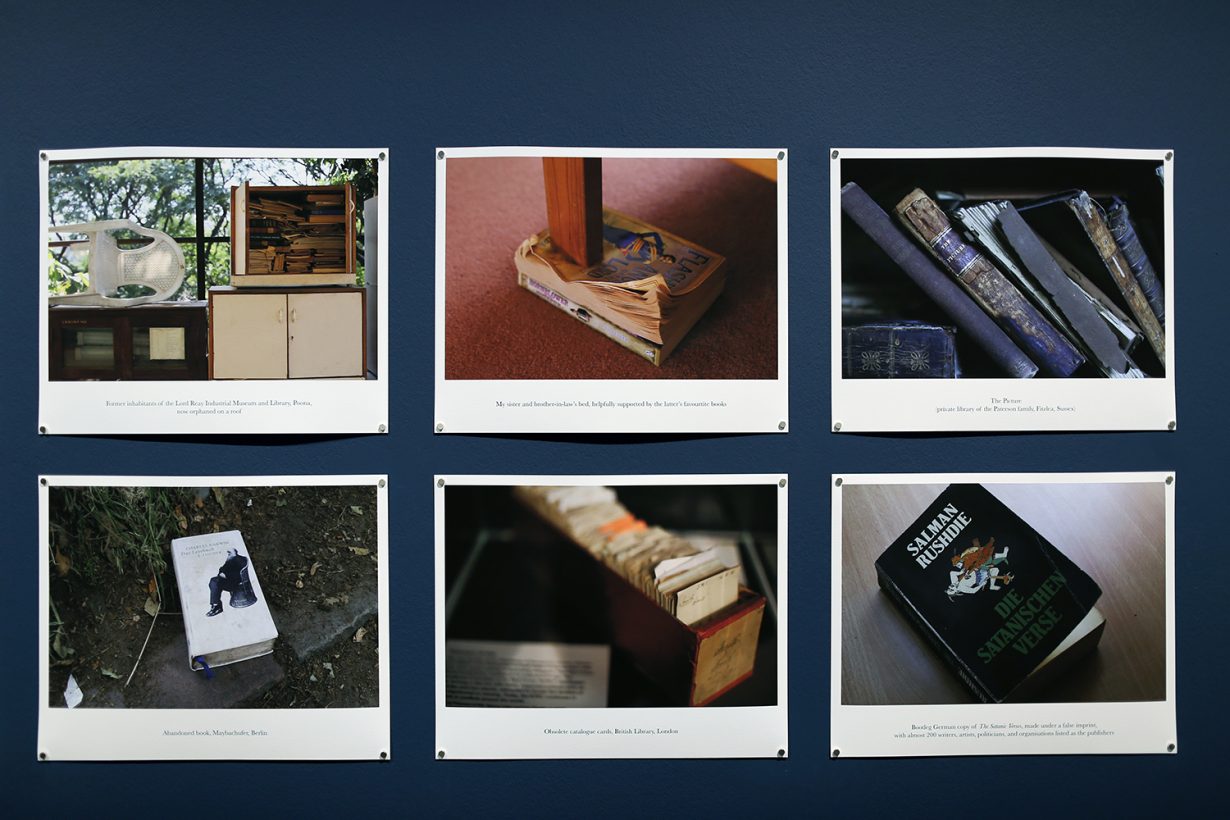

Rao’s Pulp, initiated in 2013, is envisioned as a ten-year, multimedia project (spanning film, photography and exhibitions to date), punctuated by the publication of a new book every two years. And the ground it covers goes beyond bibliography; Rao treats any repository of knowledge, not necessarily written, as a kind of library or book. A wide range of threatened ‘archives’ are also considered: from the intricate matrix of interspecies animal alarm calls to human brains. Pulp: A Short Biography of the Banished Book appeared in 2016, followed by Pulp II: A Visual History of the Banned Book in 2018, which picked up the Singapore Literature Prize for creative nonfiction two years later. Now, after something of an interruption to the routine, Pulp III: An Intimate Inventory of the Banished Book will be launched as Singapore’s contribution to this year’s Venice Biennale.

As a whole, Pulp documents both the history of book destruction and, conversely, the ways in which books have, in part or in whole, survived such attacks: the first a record of despair; the second evidence of hope. For the Singapore Pavilion, Rao will focus on the latter – the courage and resistance represented by books (and their proxies) and the people who write, read, make and save them. There will be three elements: a book; a film; and a paper ‘maze’ that, the artist tells me, will mimic the feeling of being “enveloped in the pages of a book”. The exact details are a closely guarded secret until the launch, but Rao shares that the book will include the usual bookish things – essays, interviews and artworks – as well as offering an immersive experience. The main essay will lay out an expanded conception of a library for tomorrow, which includes the voices of the historically marginalised, such as women, indigenous people and the genderqueer. Nontextual libraries, like sound and oral-history archives, also feature. Meanwhile, the hour-long film Talking Leaves (2022) comprises polyvocal stories focused on cosmopolitan print communities in Singapore and Venice. She shares some raw footage featuring Singaporean scholar Faris Joraimi speaking about batik, a textile treated with a wax-resistant dyeing technique. Like the many other disparate elements that have been folded into Pulp, this hand-crafted material, made across the Malay world, and replete with religious and cultural histories, symbolism and idiosyncrasies, can be seen as a form of text.

Rao’s passion for her subject is palpable, her conversation over-flowing with moving encounters and anecdotes. In Venice, she was particularly touched by Iveser (or the Venice Institute for the History of the Resistance and Contemporary Society), an organisation devoted to chronicling Second World War resistance in the Italian city, including records of women’s wartime stories. “Everything has meaning,” she says. A rose garden had been planted to commemorate the Italian victims of Ravensbrück concentration camp for women; and a special tree planted for Armin Wegner, the only German writer to openly denounce the treatment of Jews under Nazi Germany. “People say, ‘Books! So boring! Who cares?’ But there are these stories,” and here her voice softens, “and I want to share them with everyone.” So, who does care? Those who don’t probably won’t change their minds anytime soon. It’s an issue I’ve been wrestling with in relation to Pulp itself: that it risks simply preaching to the choir. Its audience is probably book lovers, who don’t have to be convinced of the importance of books or the values they represent. Which isn’t to say that the other readerly rewards in Pulp are not rich or meaningful, not least in the way in which the volumes allow the past to converse with the present.

Containing numerous narratives of war and conflict, Rao’s books have been published amid wave upon wave of threats to democracy and freedom of expression, giving them a bleak but eternal currency. Pulp II came out in 2018 during the first year of Trump’s presidency, alongside the rise of sectarianism and far-right movements around the world. The book contained a long section devoted to the destruction and rebuilding of the Vijećnica library in multicultural Sarajevo, which was bombed in 1992 by Serbian nationalists during the siege of the city. In 2018, the reference to such brute terrorism read like a timely reminder of what can happen when nationalist sentiment and aggression go unchecked. In 2022… Well. Perhaps ‘reading’, in all its forms, really is in decline…

There are bookish children, and there are bookish children of bookish parents with a fantastic library in which to lose oneself. Born in Mumbai in 1975, Rao spent part of her childhood in Darjeeling and the jungle outskirts of Kaladhungi, then a village in the foothills of the Himalayas. Access to her parents’ beloved library, described in Pulp I as composed of natural and political history, literature and travel, is one of her formative influences. But over time, it suffered several losses (robbery, termites) before being torn apart during her parents’ divorce, when she was a teen. So, while her subsequent research in library destruction around the world is a testament to a lifelong bibliomania, it also a way of processing personal loss.

Rao’s knowledge – and her thirst for it – is apparent in any conversation with her. She has said repeatedly in interviews that she was constrained by misogyny in India. Her first degree, from Delhi University, was in English Literature. In 2002 she moved with her partner to Singapore, where “(she) felt human first and female second”, she tells me. She completed her diploma, BA and masters at Lasalle College of the Arts and taught there for 11 years.

The misogyny she grew up with left a mark. For ten years or so she created works under the pseudonym S. Raoul, an imaginary senior male polymath to whom she pretended to be an assistant and protégée. Under that moniker, she wrote pseudo-scientific papers and made art in a complex deferral of authorial authority. Among them were his studies of the deranging effects of art and discoveries of immortal jellyfish. In her fictional biography, History’s Malcontents: The Life and Times of S. Raoul (2013), Rao wrote: ‘His life could be better seen as an argument for eccentricity and polymathic, indiscriminate curiosity and endeavour (without regard to its perceived futility) and most manifestly an argument against over-specialisation… An understated heretic, but a literary obscurantist, a man of the Enlightenment who behaved like a Romantic, a pedant sans sophistry who was frequently facetious’.

This turns out to be a pretty accurate self-portrait. (In Pulp I she described herself as ‘an anachronistic child of the Enlightenment with the squishy innards of an incurable Romantic’.) Pulp is less rococo in style than History’s Malcontents, but it too channels Rao’s prodigious intellect. Pulp I was an unapologetically erudite introduction to the project, ranging from authoritative discussion of the democratising effects of the print revolution in Europe to deconstructing the categories of truth and falsehood in art. Guiding this is an unshakeably earnest rhetoric, with nakedly declarative passages like, ‘The study of literature should mean the study of the world. To remove it, or to offer it to only the privileged, is to deny access to a shared human archive of a spectrum of histories, ideas, truths, conflicts and resolutions, continuities, forms of beauty and expression, philosophies and yearnings.’

To an ear used to the more modestly pitched moral registers of most contemporary art – where ambivalences are often seen as productive spaces where viewers draw their own conclusions – such direct statements sound almost Victorian. That said, there are pleasures to Rao’s clear thinking and cogency, especially when there is so much art writing that is limp, puffy or wilfully obscure. Her books, which are filled with investigative journalism, intellectual curiosity and compassion, feel refreshing and strangely cleansing.

Still, one might find more room for interpretation in the short art films in the Pulp universe, where ideas are explored with greater poetic license and poignancy. The Pelagic Tracts (2018) is a fictionalised account of a book discovered by S. Raoul – in this story, our friend is a British officer in colonial India – that maps the trade route of a group of imaginary book smugglers. Shot in Kochi and produced for the 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale (after Venice, Rao will resume her role as the artistic director of the postponed current edition of the Indian art event, slated to open in December), the video features local librarians and writers playing the roles of the smugglers and their descendants – and tackles how one might live in the wake of cultural destruction.

In A Small Study of Silence (2021), Rao examines species extinction in the human world and in nature, with the ‘language’ of the forest being composed of interspecies alarm-calls made by animals to warn each other of predators, a rich ecological lexicon increasingly endangered because of habitat loss. The elegiac mood is sustained by shots of cemeteries, nighttime scenes of forests at the edge of human habitations and looped cycles of haunting birdcalls. Rao tells me that the different strains of birdsong were recorded by her family members, who are living on three separate continents, and shared on a family group-chat as a form of private language of affection despite physical separation: “It was our way of saying, I love you, I miss you, I wish we were back in the woods together.”

In Pulp II there is a conversation with a librarian from Antwerp’s Hendrik Conscience Heritage Library about the inherent inadequacies of any cataloguing system. The library is named after the Belgian novelist and pioneer of the Flemish language (at a time when French was dominant) Hendrik Conscience, and collects texts to do with Flemish heritage. Conscience Library: this shortened form and the associations it conjures reverberates through my mind. A library of conscience. I’ve heard of sites of conscience, which mark places and events of trauma, like gulags and slave houses. But a library of conscience is something new.

Then it struck me: what Rao is doing with Pulp is building her own library of conscience – a multifarious archive of print-related texts, images and films that are linked to struggles towards justice and freedom. This reangled my perspective and reconciled me to an aspect of the project I found occasionally difficult: the lack of any coyness, slipperiness or equivocation. But you don’t get moral indeterminacy in the Holocaust Museum. You get deep, dark sorrow – and also hope.

In Rao’s Venice showcase, an inspirational model that appears in the new film and book is Baynatna, an Arabic-language library in Berlin that was started by a Syrian refugee. Beginning with a few donated books in a refugee shelter, Baynatna has grown to contain some 3,500 tomes (including German and English translations of Arab texts) and is currently housed in Berlin’s Central and State Library. Now a salon that hosts readings, music performances and workshops, Baynatna has become a key gathering point for the Arabic-speaking community and its allies. So far, Baynatna seems to have settled permanently into its current location, but perhaps true to its roots as an initiative by refugees, it makes no assumptions about permanence. Its furniture is modular and easily assembled or taken apart. But if need be, everything can be packed up and moved to a new place. Meaning ‘between us’ and serving the underserved, Baynatna makes a case for libraries being a sort of emergency van that provides underrated humanitarian aid to devastated communities. Libraries educate, console and dignify. Their destruction, as Pulp has so assiduously chronicled, is to be mourned. But where they spring up, especially in the most unexpected yet needy of places, they make fragile stands against despair.

Back to Heine: if you burn books, you will eventually burn people. Rao’s work banks on the reverse logic – if you wrote books and built libraries, you could, potentially, falteringly, build up new forms of humanity.

Shubigi Rao’s Pulp III: A Short Biography of the Banished Book is on view at the Singapore Pavilion in the Arsenale as part of the 59th Venice Biennale, 23 April – 27 November