In her last interview, the late artist and activist retraces the origins of her revolutionary work, which still fuels the language of Chilean protestors today

Introduction by Oliver Basciano

Interviewed by Alexia Tala

The protests that spread across Chile last year, violently and often lethally suppressed by the police and army, were sparked by a rise in fares on Santiago public transport. This issue was a pretext for expressing long-simmering resentment towards a political system and constitution with roots in the dictatorship years of Augusto Pinochet, together with an underlying fury at a pervasive inequality that had allowed a tiny elite to control one third of the country’s wealth. One recurring symbol of the unrest, the plus sign, appeared in numerous settings: in November thousands protested violence against women under banners reading ‘No + violencia’; a month earlier a demonstration in solidarity with the indigenous Mapuche people united behind a banner reading ‘No + represión’. And on 25 October, among the millions attending the biggest demonstration in the country’s history, one protester was photographed on the Plaza de la Dignidad in Santiago holding the country’s flag aloft, a ‘No + abusos’ painted across the white canton and into the red. Whether or not the photographer or protester knew it, this image recalls a famous photograph from a protest held on the same spot on 5 October 1988, in which, celebrating the results of a referendum that would lead to Pinochet’s removal, someone straddled the central statue, of the nineteenth- century soldier and politician General Manuel Baquedano, holding a ‘No +’ sign aloft.

‘No +’, which when spoken aloud reads as no más – no more – is a shorthand Chileans have used to express their discontent for more than 40 years, a sort of political proto-meme adopted by successive generations and diverse groups. Like all memes, the origins of the ‘+’ might be obscure to those using it today, and indeed it has gone through a series of translations and mistranslations before appearing on protest banners and being graffitied on walls in twenty-first-century Chile.

It first proliferated in the work of Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA), a political art group formed in 1979 by artist Lotty Rosenfeld, with poet Raúl Zurita, sociologist Fernando Balcells, novelist Diamela Eltit and fellow artist Juan Castillo (Rosenfeld had previously worked with Castillo on Espacio Siglo XX, an artist-run gallery in Santiago). Driving home from one of the first CADA meetings, Rosenfeld noticed, as she kept her car to the right of the road markings, that the white dotted lines could be considered symbolic of the control the Pinochet regime held over the public. Shortly afterwards, she returned to the same stretch of road to create what would become her most famous work: gluing stretches of white textile across each strip of white paint, she replaced a mile of traffic lines with a mile of crosses.

One of the easiest accusations to make about political art is that it lacks political power. Art, whatever the claims made by those championing its importance, is a niche interest. Yet occasionally a creative gesture seeps through into mainstream consciousness, providing a space in which resistance can coalesce. This was the case with Rosenfeld’s A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement (1979). Turning the linear dashes into crosses provoked myriad readings, none of which, Rosenfeld says, she anticipated: the crosses turned a negative into a positive; they disrupted the path the country was heading down; they were markings of state murder, signs of martyrdom.

CADA recognised the power of the sign and adopted it in its subsequent political actions, using it on antiregime pamphlets they airdropped over poor districts in the country or placing them across politically sensitive sites as if to demarcate a target. In 1982 Rosenfeld taped a series of white crosses on the pavement outside the White House, and along one of the four lanes of Pennsylvania Avenue, with the title An American Wound, a reference to the US backing of Pinochet. Other, similar interventions were made: in the Cristo Redentor tunnel, which linked Chile and Argentina, and at the Santiago Stock Exchange, where, as the country slipped into serious recession in 1982, she broadcast images of her White House action on the stock monitors. The cross quickly gained a life of its own, appearing in places and situations unrelated to Rosenfeld and CADA.

Washington, DC. Photo: Ana María López. Courtesy the estate of the artist

Rosenfeld died in July, though she lived long enough to see the continued influence of her action. Sensing his precarious standing, Sebastián Piñera, the billionaire Chilean president, has promised change, sacking cabinet members and announcing a referendum on replacing the country’s constitution – a relic of the Pinochet era implying continuity with it. That was supposed to happen in April, but because of the COVID-19 pandemic it has been pushed back to October. The crosses will no doubt reappear, a legacy she is proud of, Rosenfeld says in her final interview, with curator Alexia Tala, in January this year. Here ArtReview publishes an edited excerpt from the conversation, published in Calendarios de Arte Contemporáneo – Lotty Rosenfeld, the first in a series of books featuring monthlong artist interviews conducted by Tala via daily correspondence.

Alexia Tala In one of our first conversations, in 2008, you told me that it was only in 1978–79 that you felt comfortable in the artworld and with what you were doing. Tell me about that.

Lotty Rosenfeld Exactly. I felt that something did not fit. I was uncomfortable during my time as a printmaker, being involved in resistance to the dictatorship in parallel with an artistic production that was decorative in style. Even though it was a manual, solitary and silent work that I loved doing, I felt I had to give it up. In 1977, when I began to participate in the Espacio Siglo XX, my antidictatorship activity began to catch up with my artistic one. The next step was CADA.

However, from a different perspective, now that I am seventy-six, I finally concluded that I have always found it difficult to feel comfortable in the artworld. In the context of our basically patriarchal culture, I have had to face all the foreseeable limitations, delays and obstacles. However, I must admit that my work has sometimes overcome these obstacles on its own.

AT You had small children, how did you combine family life, art and political activism?

LR Yes, I have two children, Ramón and Alejandra. The 17 years of dictatorship were diffcult for me and my whole family. Trying to harmonise these three aspects was complicated. There was a lot of anger, fear and sorrow about what was happening in Chile every day. It was essential to give everything one had to ending the horror, and of course maybe I neglected family life to be present in all the resistance spaces where I could be. Working with CADA took up a lot of time, we would meet to work every day sometimes on the edge of the curfew, we really didn’t have a timetable.

During the Popular Unity government [of Salvador Allende, 1970–73] and throughout the dictatorship [1973–90] I was a member of [political party] MAPU. My cell consisted mainly of artists from different disciplines, and a party newspaper was mimeographed in my house. In 1983 I was invited to join the multiparty group Mujeres por la Vida (Women for Life), where I designed posters, murals, leaflets and protest actions. I took photos and filmed on video the mobilisations as they happened. The greatest contribution was the work that Diamela Eltit and I did creating slogans used by the women’s groups. They took over these slogans in their mobilisations, such as: ‘WE ARE +’; ‘NO + BECAUSE WE ARE +’; ‘WOMEN VOTE NO +’, emblems that were a sort of extension of the NO + that CADA worked on.

AT How do you remember CADA today? What was the collective’s impact on your later work and your way of thinking about art?

LR In its beginnings, CADA gave strength and meaning to my work. Very few dissident initiatives could be expressed openly, and in this context it became essential to me to reformulate my role as an artist and to work collectively on a common project. As an artist, I shared the imperative of CADA, to establish a critical reflection about the mechanisms by which art is produced and circulated. From that point on, an interest in the political situation and the problems it raises has been a constant theme for me in all these years.

AT I would like you to travel back in time and tell me what you felt when you were driving down Manquehue Avenue and you began to see the broken lines of the street go past the side window. What was it like and what did that moment of clarity hold when you decided to intervene?

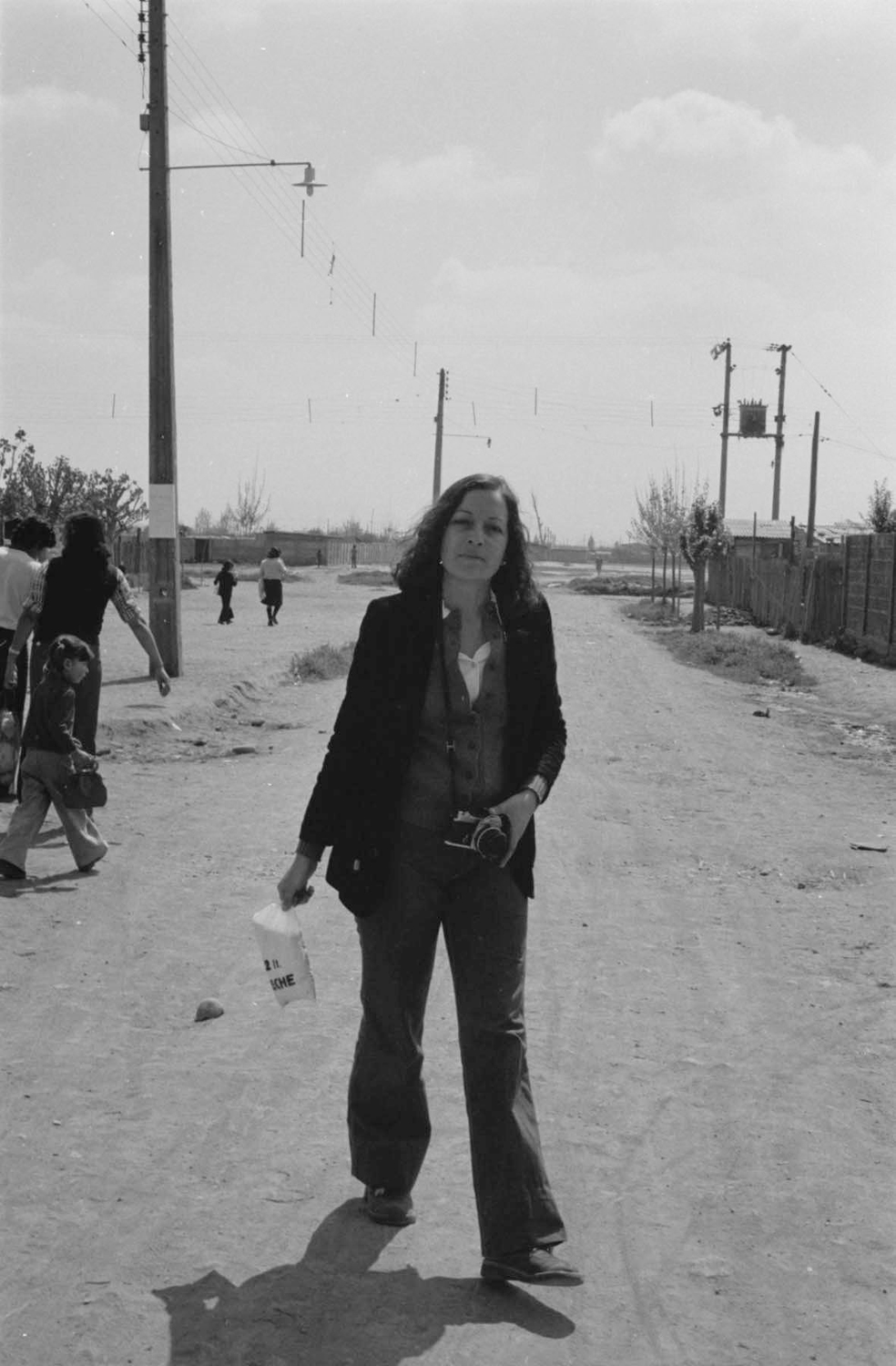

La Serena, Chile, 1984. Photo: Paz Errázuriz. Courtesy the estate of the artist

LR I clearly remember when I first perceived the segmented lines in the street. Until that moment I had merely obeyed their ‘mandate’ [as road markings] automatically. I remember going down a street at night without any car blocking my vision of the white lines in the middle of the street. As I told you before, I had come from a CADA meeting. It was 1979 and at that stage I was itching to carry out my own art action, I was looking for a sign, a point to start from.

That night as I drove to my house and saw those segmented lines one by one, one succeeding another, dividing the route, the idea came to me of working with them. An imprecise idea, still to be defined. Crossing them? The next day I told the CADA members (somewhat unsurely) about my discovery, and they immediately encouraged me to study it further.

AT With your first intervention, that first cross, the consensual order of the traffic sign was altered by art, as an activity independent of life, independent of politics, but which at that moment merged and became inseparable from them.

LR It is indisputable that at the beginning my work was ahead of me. It challenged me to face questions that I had no answers to. I was being presented with another language, a nonverbal one that was foreign to me, I was learning on the job.

Photo: Rony Goldschmith. Courtesy the estate of the artist

It was clear that the action of constructing a plus sign from a minus sign that is present in all the streets and avenues along which one travels had extraordinary potential. Since my first intervention in 1979, due to the need to surpass the time limit of an art action, I felt I must look for a means of multiplying duration. So video was used to document the action. I repeated the action, and projected the previous documentation in the same place. It was my first video installation. I didn’t know that these nightly projections would be called multichannel installations in the future. The use of video as an art medium progressively expanded the communicative potential of my work as it developed.

AT How has the passage of time affected the work if you compare the context in which it was carried out with that of Chile today?

LR Times change and one changes with them, and the passage of time proves the validity of my intervention of the sign. Globalisation and technological advances have expanded and democratised in favour of my work. The new times provide opportunities to interrogate the mandates and denounce the various ways in which ‘power’, the great ‘watchful eye’, operates, moulding us as it pleases with the sole purpose of making us economically profitable.

Having marked the White House in 1982, in An American Wound, and occupied the Stock Exchange the same year (when Reagan was president and we were in the middle of the dictatorship here), my intention then was to connect places marked by different economies of power, of violence, of economic concentration. Seeing the images of those actions today, we run through the history of both sites of intervention: from Reagan to Trump (the empire), from Pinochet to Piñera (neoliberalism). It is a work whose metaphorical potential goes beyond the context in which it was conceived.

In today’s Chile, after the ‘social explosion’ that started on 18 October 2019, my intervention and the CADA slogans (‘NO +’ and ‘WE ARE +’) multiply, and their power to convene is indisputable. Today I received a photo of a block of + signs traced on an avenue in Valparaíso. This was not my intervention – it was right among the barricades.

AT If we think of representation as a shared area for art and politics, how do you see this sharing of the same space? Do you have something to say about the stability or instability of that space of art and politics?

LR I think we need to rethink the connection between art and politics, starting with an innovation of languages based on economic, social and cultural policies, establishing a tension between what is internal to institutions and what is external to them. On the one hand, spaces that belong to an art tradition such as museums, galleries and closed spaces; on the other, the outside, the urban space, the space of citizenship, of the social and the political. As far as my work is concerned, it continues to interrogate social orders, from the Chilean dictatorship to, most categorically, the present, with works that show how the world order is sustained by an extensive and powerful speculative network. The art–politics relationship does not mean that art thematises politics; the work of art compels us to rethink politics.

Translated from the Spanish by Sebastian Brett. Alexia Tala is curator of the 22nd Bienal de Arte Paiz, Guatemala City