The late artist unsettled our tired ways of seeing with a constant freshness of attack

With the death of Frank Auerbach, we have lost a very great artist. During a period that included fast-changing methods and the arrival of American art in Britain, he held fast to his own individualistic, expressive style. His single-mindedness and dogged persistence slowly gained him immense admiration and respect. Early on in his career, he had found himself marvelling at Turner’s depiction of a slow-turning warship aided by two steam tugboats, in The Fighting Temeraire (1839). He took away from this picture the need to break rules and to make leaps into the unknown. Thereafter, Auerbach’s method of working kept him on edge, uncertain as to how a picture might progress. Often its arrival at completion caught him by surprise.

Auerbach was born in Berlin in 1931. Shortly before he turned eight, his parents, aware of the danger Jews faced in Hitler’s Germany, seized the opportunity to send him to school in England. Auerbach, however, once pointed out that it was the writer Iris Origo, who made this possible by guaranteeing payment for six children to attend Bunce Court, a mixed education boarding school with a Quaker ethos. Auerbach found the school liberating, if slightly puritanical. Red Cross Letters made postal communication with home possible every three months, until this line was blocked. He heard no more from his parents. Eventually he learned that both had died in one of the concentration camps at Auschwitz. By then fully at home in England, he decided to move forwards rather than back, and put his family out of mind. Or did he? The two suitcases he had brought from Germany held different assortments, his current clothes and sheets in one and, in the other, clothes and sheets for future use. His mother had distinguished the latter by sewing a large criss-cross in red cotton on each item. Many years later, in his landscapes based on Primrose Hill, Auerbach used bands of red, which in one picture zig-zag across the blue sky, as if in echo of his mother’s embroidery.

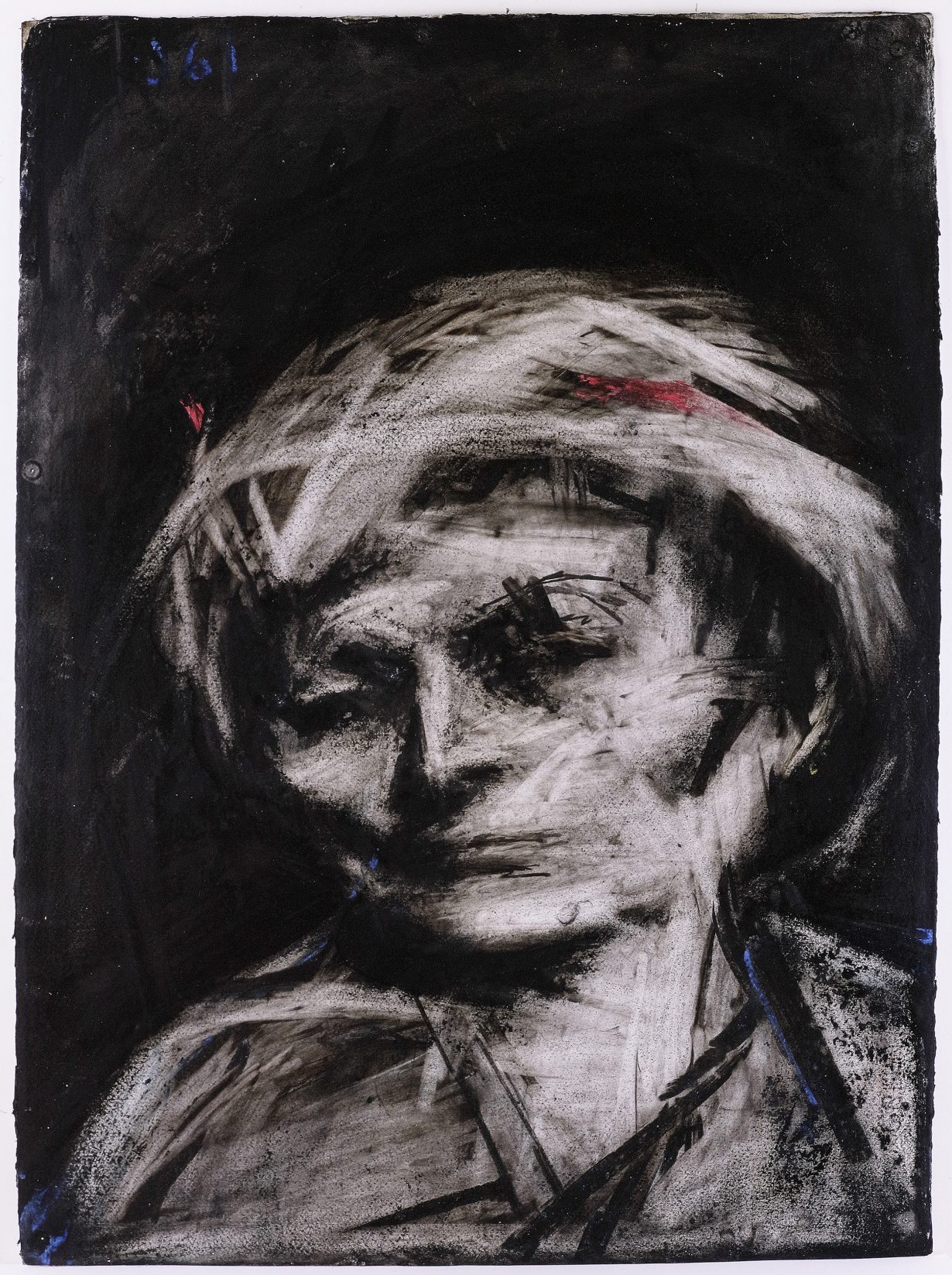

Of central importance to Auerbach was his debt to artist David Bomberg. At the Borough Polytechnic, Bomberg set up a drawing class that was opposed to the academic tradition. It drew a loyal following. Auerbach arrived in 1948 and continued attending these classes two evenings a week until 1954, even after he had passed through St Martin’s School of Art and had entered the Royal College of Art. A perfectly finished, carefully modelled, and well-proportioned life drawing was, Bomberg thought, a complete lie. It ignored the fact that we see in bursts and arrive at our knowledge of the figure through piecemeal reconstruction. He also urged students to feel the part played by gravity in anchoring ‘the weight, the twist, the stance of a human being’. Under Bomberg, drawing became, not a record of surface appearances, but a deeply emotional response to the physical facts of existence. It chimed, at this time, with the weight of moral responsibility that Existentialism placed on the individual. Bomberg’s teaching became the backbone for Auerbach’s draughtsmanship, while also tying in with his interest in questions of identity.

The main standard bearer in his life was nevertheless London’s National Gallery. He and Leon Kossoff made it their habit for some three decades to visit it weekly and make drawings in front of certain works of art. These became touchstones, reminders of quality, even while Auerbach was expressing a sense of postwar deprivation through his use of the cheaper earth colours, and in those ghostly scenes composed solely in black, white, and grey. His fascination with London began with the reconstruction of its war-torn parts. The rawness of a building site and the directional thrust of girders and ladders became the means through which he, too, could rebuild order and coherence in paint. As time went on, he extracted from a wide variety of art of the past what he wanted to find in his own art. As he told Catherine Lampert in 1978, he wanted ‘somehow to make something that has a similar degree of individuality, fullness and perpetual motion’.

His early work startled many with its extreme thickness of paint. It hung often in great viscous clots and drips and was dragged or flicked brusquely into position. In one Head of Gerda Boehm (who sat for the artist every week from 1961 to 1982), the head is almost modelled in such a way that we are able to look under her chin as we would with a sculpture or relief. In some paintings the paint is so thick that it almost takes on a state of decay, for as oil paint dries, it wrinkles, sags and begins to suggest the puckering of flesh. But it is impossible to ignore the fact that given to many of his early heads is also the weight of sadness.

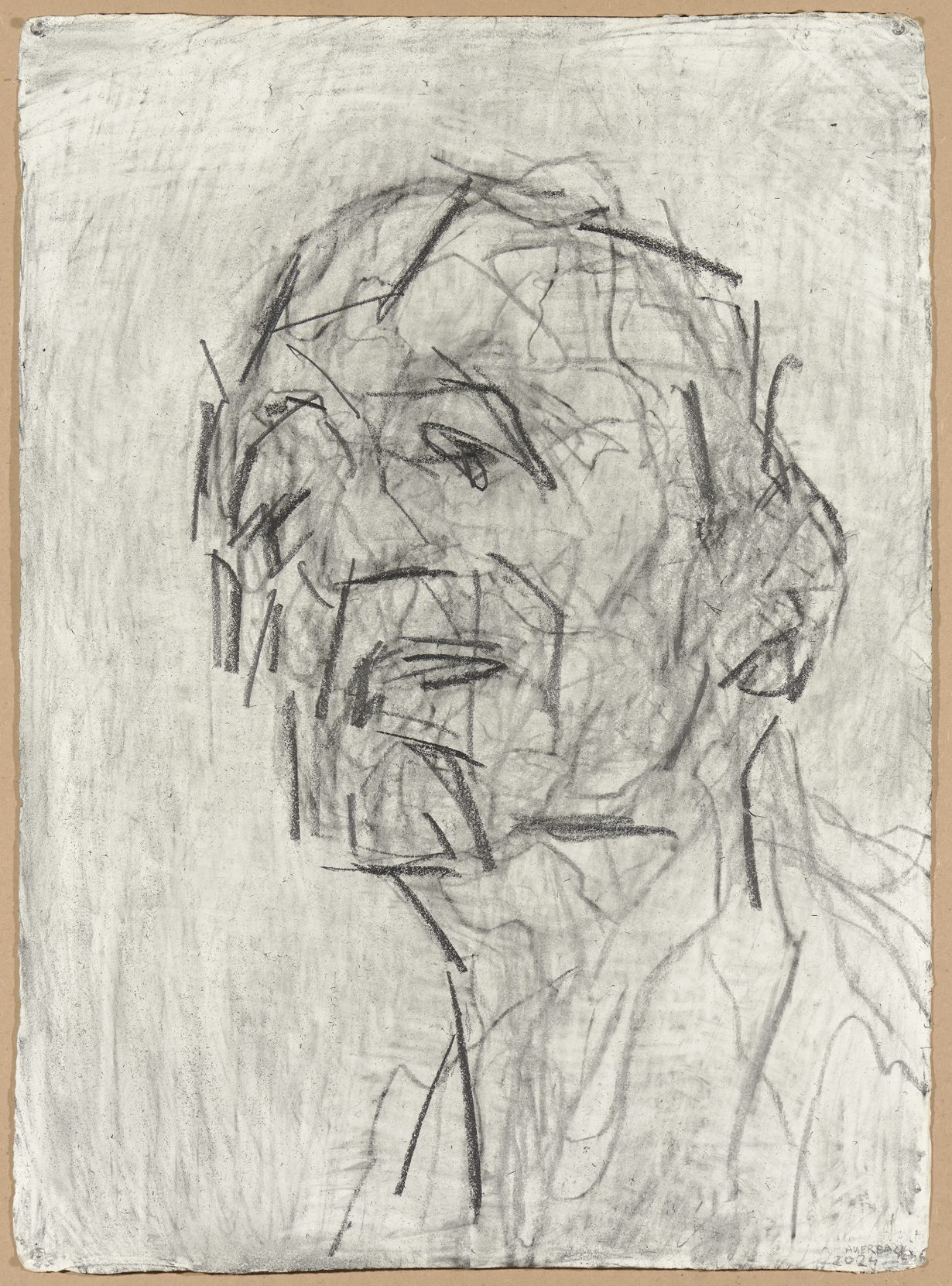

Before long he developed a more fluid and mobile approach, moving the eye around the picture with unexpected lines of force and sudden changes of direction. His palette also became less fixed, his chromatic range altering according to the mood of the subject. A great deal of scraping down went on, so as to start afresh each day. Auerbach’s searching method meant that his paintings continued to pass through many nuances and transformations before completion was achieved. His exhibition history began when he joined the Beaux Arts Gallery and formed part of Helen Lessore’s stable. When this closed he moved on to Marlborough Fine Art. He was given a major exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1978; showed in 1986 at the British Pavilion in the Venice Biennale; and in 1999 Robert Hughes referred to him as ‘one of the most admired artists working in England today.’

None of this could have been achieved without his relatively small studio in Camden Town, North London, into which he moved in 1954 and never left. Here his sitters came and went, every week; at fixed times, for years (and, in some cases, for decades), thereby demonstrating extraordinary loyalty to their task. Meanwhile eccentricity in Camden Town flourished as did the crowds, especially for Camden Lock at weekends, when the London Underground is often unable to cope. Roofs fall in, passengers are regularly kept out when the station reaches capacity. Auerbach loved its madness and vitality.

He also loved Rembrandt and one of his most judicious exhibitions was in 2001, when he shared the grand first-floor galleries in the Royal Academy with ‘Rembrandt’s Women’. One item included was the copy he created of Rembrandt’s small Deposition (from the collection of the National Gallery), making of it a strikingly large, terse analysis of its abstract components. Mindful of his own experience of seeing a Rembrandt by chance in a public gallery, he too wanted to ‘turn the curious nullity of a silent man by himself in the studio into something that happens with tremendous luck 300 years later to somebody who is visiting a gallery’.

Most of the cityscapes he painted are in or close to Camden Town. There are grand assaults on Primrose Hill, at different times of year, and views of Mornington Crescent, churning with movement and strong colour. In some paintings, such as a view of Park Village East-Winter (1998-9), blunt, cursive strokes render houses, trees, and wheeling clouds with exuberant celebration. This constant freshness of attack unsettles our tired ways of seeing. We know the artist has succeeded in his aim when we, too, begin to find a certain glory in the familiar, the ordinary, and the overlooked.

Frances Spalding is an art historian, biographer and critic