‘There is something wrong with our present society, and I can’t stand SF written by people who don’t understand that,’ she once wrote

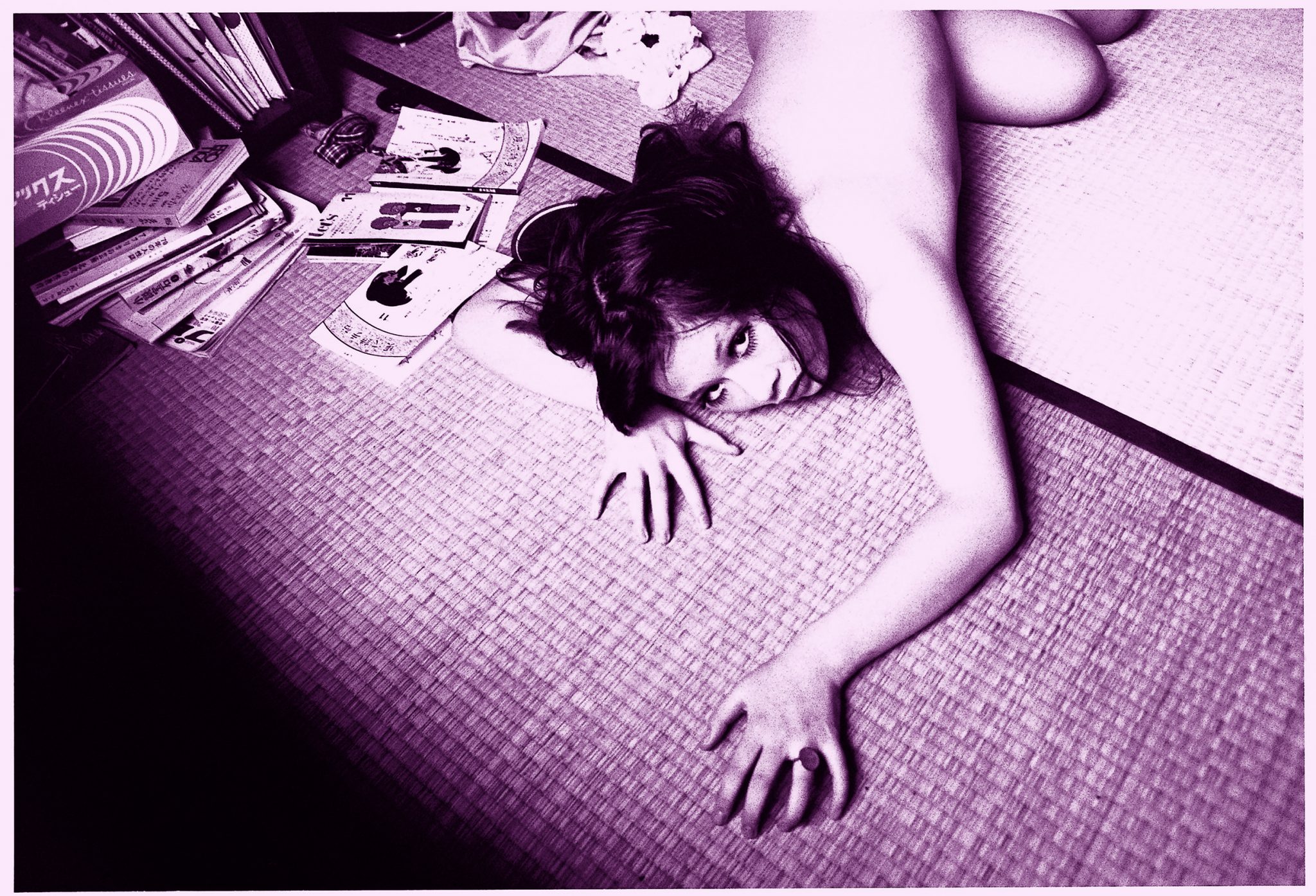

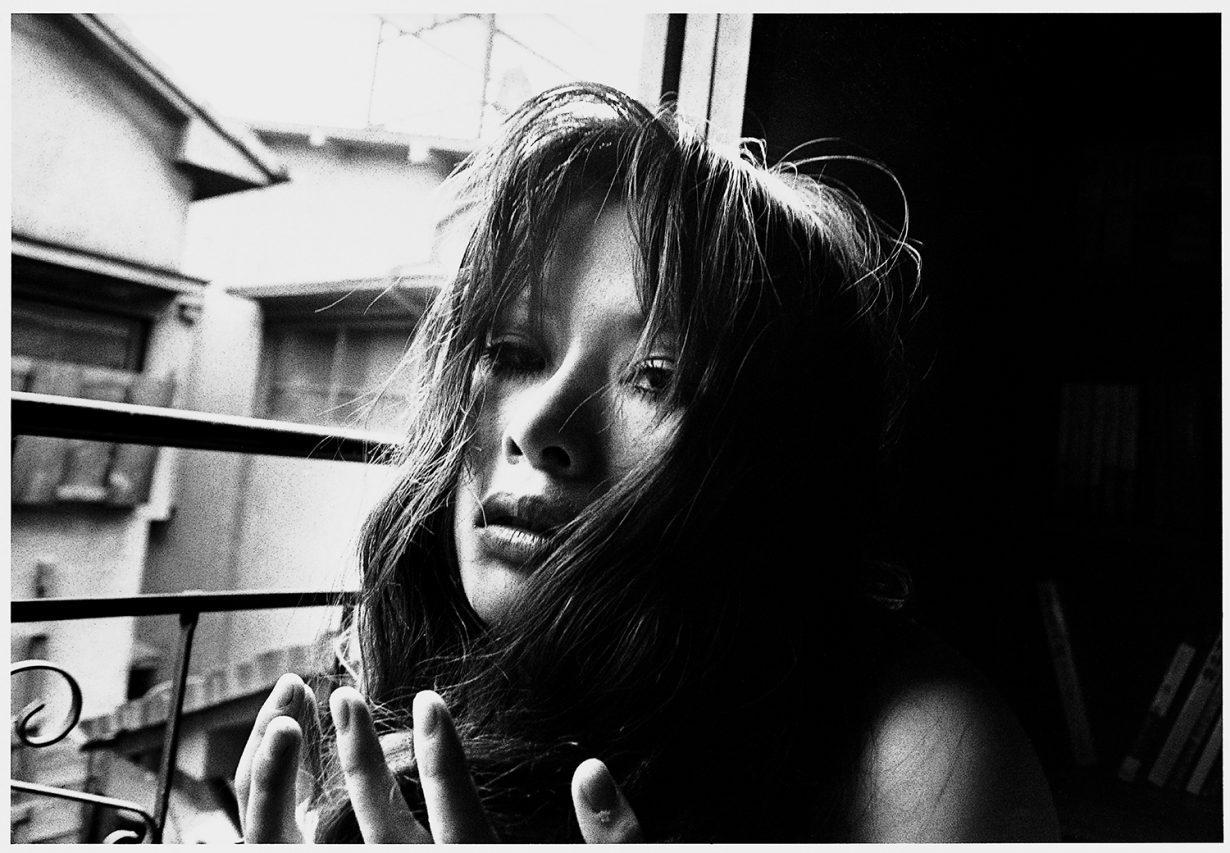

Izumi Suzuki was born in 1949 under the Allied occupation and came of age during the 1960s, an era of drugs, rock and roll, and nationwide protests in Japan as it was elsewhere. After high school she worked briefly as a keypunch operator at Itō city hall, but soon quit to pursue writing, acting and modelling, working with the controversial photographer Nobuyoshi Araki as well as maverick directors Shūji Terayama and Kōji Wakamatsu. In 1973 she married the free-jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe, with whom she had a daughter. The couple’s notoriously tempestuous relationship, dramatised in Wakamatsu’s 1995 film, Endless Waltz, ended in divorce in 1977, and Abe died from an overdose of Bromisoval the following year. Suzuki produced the majority of her work, and her best science fiction, in the last ten years of her life, which ended with her suicide at age thirty-six, in 1986. Science fiction (or SF, as it is routinely called in Japan) liberated her writing, providing a playground in which she could deconstruct a male-dominated Japanese society and her relationship to it, laying the groundwork for generations of authors to come. The academic and critic Mari Kotani writes, ‘It is not an overstatement to say that the age of [Japanese] women’s SF – wherein women discover and reconstruct femininity – began with Izumi Suzuki, who lived through her science fiction.’

Suzuki started writing SF as early as 1972, publishing five strange, unsettling stories in addition to her mundane fiction, but she truly came into her own with ‘The Witch’s Apprentice’, published in a special ‘women’s issue’ of SF Magazine in November 1975 alongside translations of work by such luminaries as Ursula K. Le Guin and Marion Zimmer Bradley. During the 1970s, the world of Japanese SF, like the literary establishment in general, was a literal boys club – in a 1977 interview featured in the magazine Kisō Tengai, Suzuki half-jokingly asks SF doyen Taku Mayumura if she might join the SF Writers Club, of which none of the 30 or so members are women. He laughs it off.

The critic Nozomi Ōmori writes that Suzuki and her few female contemporaries were ‘treated by the SF community as outsiders, or perhaps “tourists”’. People were confounded by her work, and focused more on her eccentric biography than on the stories themselves (her brief stint as a nude model and in softcore ‘pink films’, as well as the time she cut off one of her toes in front of her husband, have tended to dominate the conversation). But as Ōmori says, ‘Readers back then probably just couldn’t keep up. No SF author at the time was writing anything like her.’ Suzuki’s defiance of both social and literary norms paved the way for subsequent authors from Haruki and Ryū Murakami to Yōko Tawada, Gen’ichirō Takahashi and Amy Yamada, but (along with her infamously acid tongue) also likely contributed to the fact that she was never accepted into the canon.

Suzuki has drawn comparisons to Western authors like Marge Piercy, James Tiptree Jr (another woman who began producing SF later in her career) and especially Philip K. Dick, whose tales of social alienation and drug use are similarly ensconced in a futuristic mode. I would add Anna Kavan to the list; like Kavan, Suzuki is unsparing in her use of SF to expose and examine the self. Her work is highly personal, but the artificiality and distance afforded by SF invigorates her writing, opening the way for a more honest engagement with the collective delusion we call the ‘real world’. For Suzuki, everyday life is science fiction, and her sense of alienation from and suspicion of contemporary society was intimately linked to SF. In her words, ‘There is something wrong with our present society, and I can’t stand SF written by people who don’t understand that… Even when you’re talking about some future society, if you write with full faith in our present world, then nothing changes, you just end up with the same ideas we already have.’

It comes as no surprise, then, that Suzuki’s stories are deeply rooted in the counterculture, with all its antiestablishment and antiauthoritarian implications. In the end, however, the focus of her work is largely domestic. Most of her stories return to troubled relationships between men and women, and in a world of ready interstellar travel, we seldom leave Tokyo. Suzuki is fascinated with how the fundamental struggles of everyday life persist regardless of what new technologies infiltrate our lives. For Emma, the protagonist of ‘Forgotten’ (1977), advanced technology represents a means to indulge both her drug addiction and suspicions of her lover’s infidelity. In ‘Terminal Boredom’ (1984), advances in neuroscience serve only to opiate a society driven to the brink by unemployment and apathy. Suzuki’s uncompromising, though often darkly humorous, stories represent a kind of SF version of kitchen-sink realism, told from the perspective of the one stuck doing the dishes. The realities of everyday life are never far away. The virtual world of ‘That Old Seaside Club’ (1982), for example, uncannily prefigures the popular feel-good Black Mirror episode ‘San Junipero’ (2016), but dispenses with the touching ending in favour of a grim return to the drudgery of an unhappy marriage.

Gender is somehow both central to Suzuki’s work and beside the point. As such, the gender dynamics of her stories may feel strange to contemporary readers. She blazed her own trail in the SF world, and this extended to her politics as well. Kotani writes, ‘During the period of the women’s liberation movement, when Izumi Suzuki dominated the SF literary milieu, feminist separatism was translated into narratives of “feminist utopias”. These narratives, however, did not merely support feminist separatism; on the contrary, they revealed a certain ambivalence about it.’ Suzuki’s most famous story, ‘Women and Women’ (1977), depicts a postapocalyptic matriarchal society in which males are confined to institutional ghettos, but a sense of unease permeates this supposed utopia, leading the teenage narrator to question the values with which she has been instilled.

Suzuki’s relationship to gender and feminism is complex and nuanced, requiring the twenty-first-century reader to step outside of hard-line contemporary rhetoric. But while a contemporary mode of feminism may not be overtly apparent in her work, Suzuki often spoke out against the unrealistic feminine ideals imposed upon women by male SF authors in the form of beautiful, cookie-cutter female characters. She also dismissed essentialist stereotypes like the notion of ‘women’s intuition’, and demanded the right to be a real, flawed human being. Kotani again: ‘Suzuki’s texts defamiliarize the real world in order to demolish and reconstruct the “femininity” bound hand and foot by real-world power structures. Her works dismantle the power structures whereby women are marginalized through phrases like “only a woman would…” or “because she is a woman.” It is only through this process that one can begin to think about what constitutes “femininity.”’ But even at her most political, Suzuki is never polemical. She approaches such questions obliquely, attacking imperialism (‘Forgotten’) and casually dismissing gender as a social construct (‘Night Picnic’, 1981) in the course of depicting troubled romance and the absurdities of family life. Meaning flows through her stories like music, and despite the obvious complexities of her work, Suzuki described her writing in simple terms: ‘I turn my dreams into stories’.

Nobuyoshi Araki called her a ‘woman of the age’, but Suzuki is a timeless writer, or perhaps a writer out of time. Ōmori points out that many SF authors write about a fantastical ‘future’ that becomes old and out of date the instant we approach it; Suzuki wrote about the ‘present’, and her stories transcend a particular time, culture or place, remaining as disturbingly relevant as ever – as Ōmori says, ‘Izumi Suzuki is always an author of the “now”’.

Terminal Boredom, a collection of stories by Izumi Suzuki, is published in April 2021. Daniel Joseph is the translator of ‘Women and Women’ and ‘Terminal Boredom’, which are published as part of the collection.