In the work of the German South Korean émigré painter, the personal is political

In his most recent book, Undinge (Nonobjects, 2021), the South Korean-born German philosopher Byung-Chul Han wrote of how the accelerated flow of immaterial digital information – the nonobjects – that constantly swill around us has grossly distorted our experience of time, memory and labour, resulting in burnout, ennui and the atomisation of social relations. One of the only means we have of reclaiming some semblance of agency (and sanity), he suggests, is by slowing things down and ‘lingering with objects’. As he put it in a recent interview with ArtReview, ‘The same chair and the same table, in their sameness, lend the fickle human life some stability and continuity.’ This idea of objects as ‘resting places for life’ is interesting to consider when looking at the enigmatic paintings of another German South Korean émigré, the artist Hyun-Sook Song.

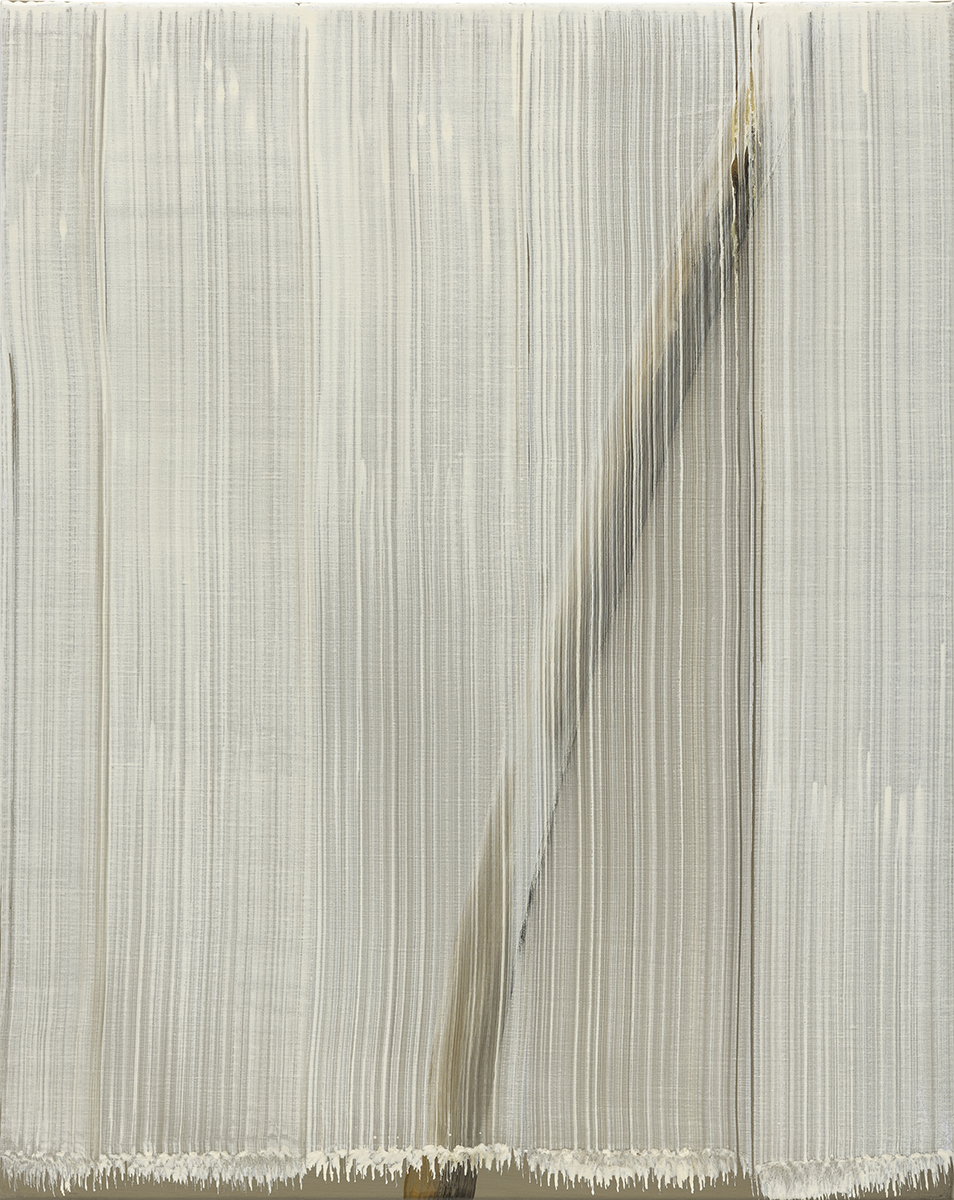

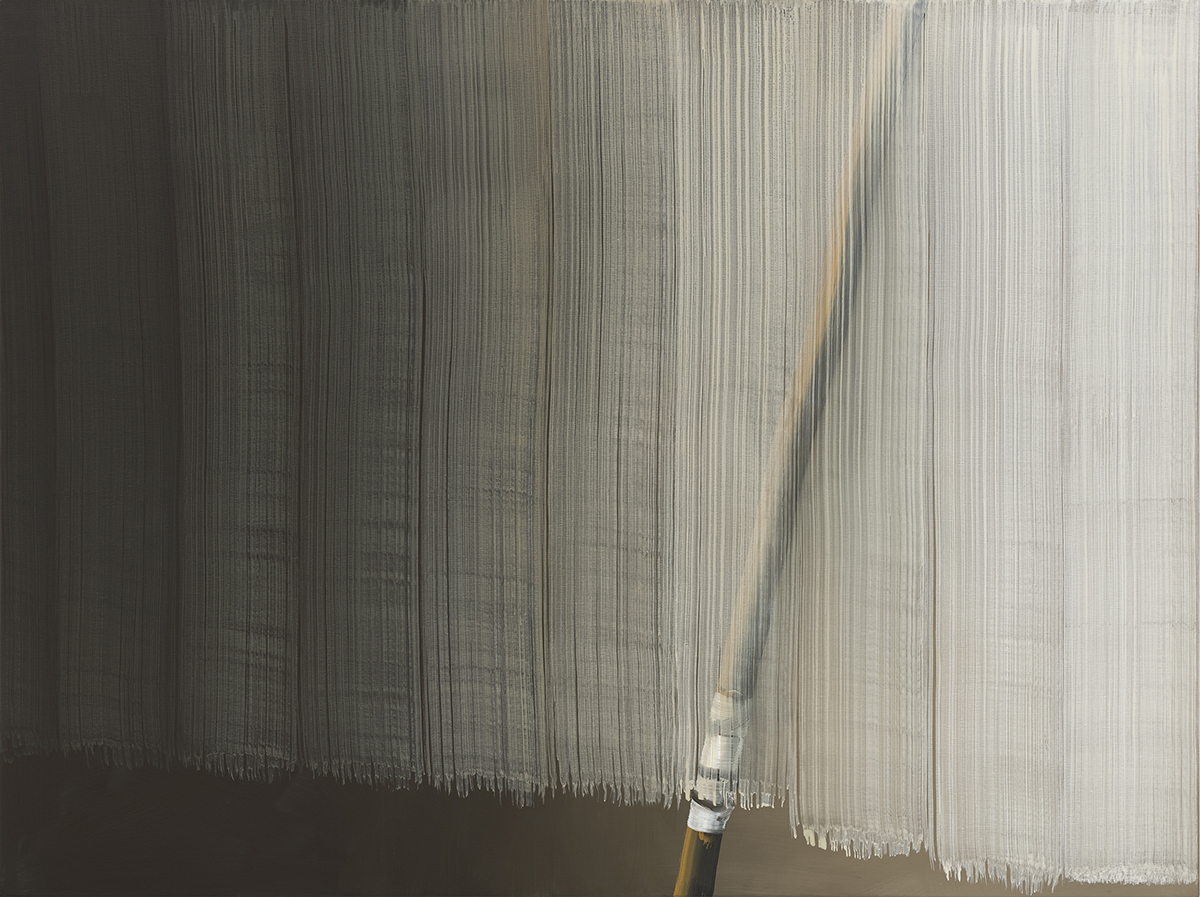

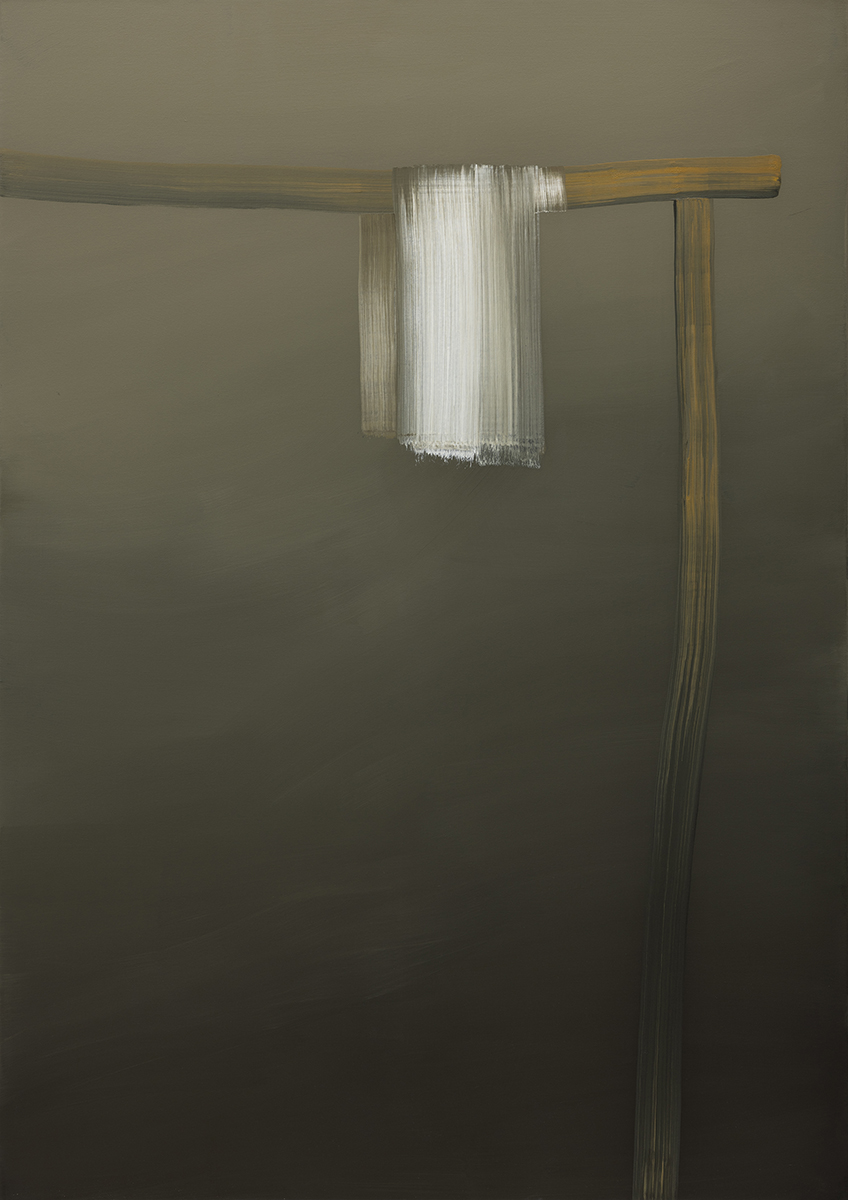

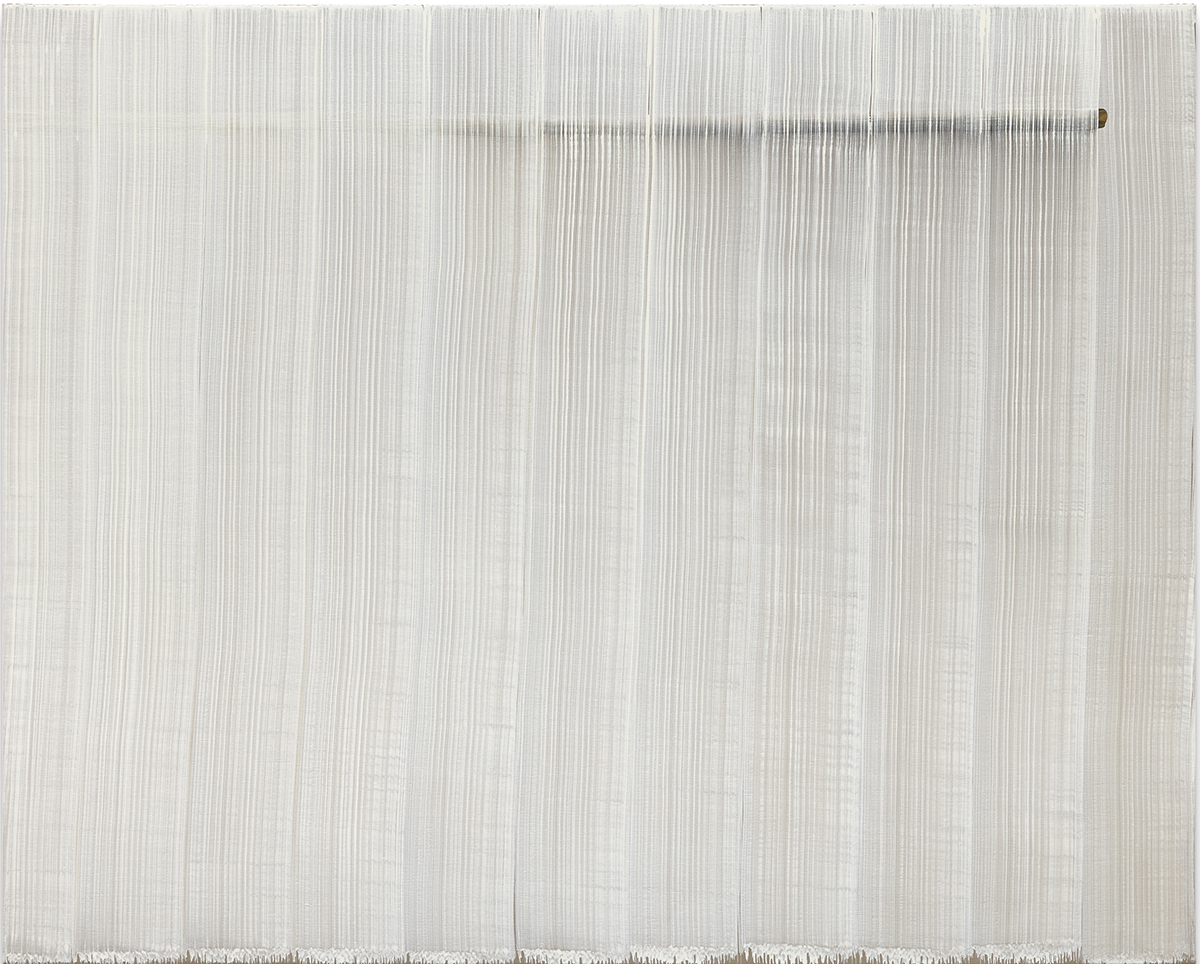

Song’s first solo exhibition at Sprüth Magers, Berlin, is a terse display of seven largescale canvases executed between 2009 and 2021. All of the works feature the organic, sinewy form of what appears to be a wooden post or branch, articulated in varying shades of burnt umber, set against a neutral backdrop. In some of the paintings, this nondescript object is veiled by gossamer washes of paint, as if curtained by translucent strips of fabric. In others, it is tightly bandaged, or else seemingly held in place by narrow swathes of white pigment that extend beyond the pictorial frame, accentuating the tensions between abstraction and figuration, support and surface.

The titles of these paintings provide no clues as to their elusive symbolism. Instead, Song’s works are typically named after the surprisingly limited number of brushstrokes required to complete each piece, orienting our attention towards the gestural, material and durational processes of their making. We can’t help but be momentarily exercised by the task – or is it a game? – that Song sets us, as we attempt to parse out each quantifiable stroke of the brush from the painting’s illusory totality. But perhaps because Song never completely abandons figuration in favour of abstraction, we still find ourselves circling back to lingering questions of iconography. What do these objects signify, and what exactly is being represented here?

The details of Song’s artistic trajectory and personal geography are useful to consider in this regard, and already quite well known – in part due to a recent biography written by her partner, the artist Jochen Hiltmann. Song was born in 1952 in the remote agrarian farming village in the Chŏlla province of South Korea. Unusually for a woman of her generation and background, she attended high school in Gwangju, and emigrated to West Germany at the age of twenty to work as an auxiliary nurse. In the mid-1970s she was diagnosed with a serious lung disease that forced her to leave her job, which led her to enrol at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg. There she began experimenting with egg tempera on canvas, combining a medium that is commonly associated with Western medieval art with an East Asian calligraphic immediacy and brevity of form.

Throughout this period, Song struggled with the estrangement that is so characteristic of migrant experience – a sense of dislocation exacerbated by the turbulent political events back home. As the artist recalled in our email exchange, “When I saw the images of the Gwangju uprising on German TV, it was traumatic. It was difficult to get information back then because the regime banned all communication. I was horribly worried. I remember that I took a little radio to Art School in Hamburg every day, so as not to miss any news. The event caused me a lot of sadness and anger. There was a sense of helplessness, since I was so far away.” Song soon became an active member of the Korean diasporic community, providing aid for exiled South Korean dissidents in Germany with the help of German artists and activists. Prior to that, Song had also been involved in the Koreanische Frauengruppe (Korean Women’s Group), fighting for equal rights for her fellow Korean nurses in Germany. While some of her early work bears some resemblance to Minjung art, and can be said to reflect her political leanings, one would be hard-pressed to find any indication of these concerns in the paintings for which she is now best known. But as Song clarified: “Artistic practice in my view is a political act in itself. It is not my way or intention to use art or painting as a tool to promote political views or activism. But I consider myself a very political person. My political awareness happened to me, I did not have much of a choice… my emotions are certainly expressed in my practice and in my works, as my emotions continue to be a driving force for my works today.” In other words, to use an oft-quoted feminist adage, the personal is political.

Indeed, despite having lived in Germany for the past 50 years, Song continues to paint objects remembered from her childhood. The wooden posts, earthenware pots and delicate strips of fabric that sparsely occupy her canvases, as Song phrased it, are “inscribed with meanings” that are not only particular to herself and her family, but to the “entire village community” in which she was born and raised; vestiges of a slower way of life and work before the advent of electricity, industrial production and modern communication technologies.

On one level, Song’s paintings can be seen to embody a sense of profound nostalgia, or rather a homesickness, for a place and time that no longer really exists, and for people who are no longer with us. Often when she is in her studio, Song recalls the craft and practice of her mother and grandmother, who, alongside the many duties of working on the farm, were also in charge of the production and colouring of silk, hemp, linen and cotton, and the making of cloth for daily use and festive occasions. By refabricating these textiles in white tempera, it is almost as if Song is performatively continuing this matrilineal form of labour across space and time, through the medium of paint. The act of painting itself is a painstaking process – indeed Song sometimes spends months producing a single work.

I couldn’t help but notice that several of the paintings in the exhibition were created during the peculiar space–time of lockdown, a period of sustained social estrangement and idleness that has only served to heighten our reliance on the immaterial panoply of ‘nonobjects’, and one that according to Byung-Chul Han has left us more exhausted and dispirited than ever before. Due to the lung disease that first forced Song to leave her job as a nurse and take up painting, Song was categorised as particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. As she put it, “My recent illness and the pandemic made me reflect on life and death. As with many others, I feel the impact of social isolation from friends and family. As my emotional state is connected to my practice, I am certain it does influence my work. How exactly, I cannot say.”

In this way we might think of this ‘lingering with objects’ as a drawn-out practice of remembrance; one that prompts us to take our time with each of her works, and contemplate the inextricable connections between the work of memory and the work of art.

I was reminded here of the South Korean author Han Kang’s collection of essays in The White Book (2016), a Proustian account of ordinary white items – such as the moon, rice, blank paper, a lace curtain, a shroud – that triggered ineffable associations in the author, bringing to the surface long-submerged childhood memories of grief and loss. For Han, and perhaps for Song too, the act of giving form to these resonant objects in themselves has a transformative, and even curative, potential: like ‘a white ointment applied to a swelling, like gauze laid over a wound’.

Paintings by Hyun-Sook Song are on view at Sprüth Magers, Berlin, through 26 March

Wenny Teo is an art historian and curator. She is Senior Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Asian Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London