Over the course of the year, in a dingy basement in Nottingham, artworks are slowly being consumed by mould, fungi and bacteria

There’s unknown life lurking in the cellar, its sporadic growth unencumbered by human intervention. International House of Grot, located in an unassuming terraced property in Nottingham’s Sneinton district,isn’t an exhibition for you or me but for ‘them’: moulds, fungi and other less familiar parasitic lifeforms that revel in the damp and darkness, ready to latch onto unsuspecting objects. Craig David Parr is host to these organisms, or more precisely his house is. In the intimacy of his cellar, artworks are pitted against the festering conditions of poorly maintained rented housing. This exhibition mimics the isolating effects of 2020, with works confined to an internal domestic space for an entire year. For the duration of 2021 the show will only be accessible online, culminating in an end-of-year opening, at which the objects will be exhumed. Until then, contact with the work is through periodic updates on Instagram, with dimly lit images revealing their slow but inevitable biodegradation. It’s hard not to identify with these art objects as they undergo an experience that is oddly familiar – sitting at home and rotting.

Negotiating artworks through Instagram posts, the grotesque conditions of the cellar they’re sat in takes on a speculative quality, as our access is governed by these small windows onto their putrid lair, leaving much to the imagination. This framing of the work lends an air of abject horror to this mouldering exhibition, the gap between the object and spectator adding to the anxiety of viewing.

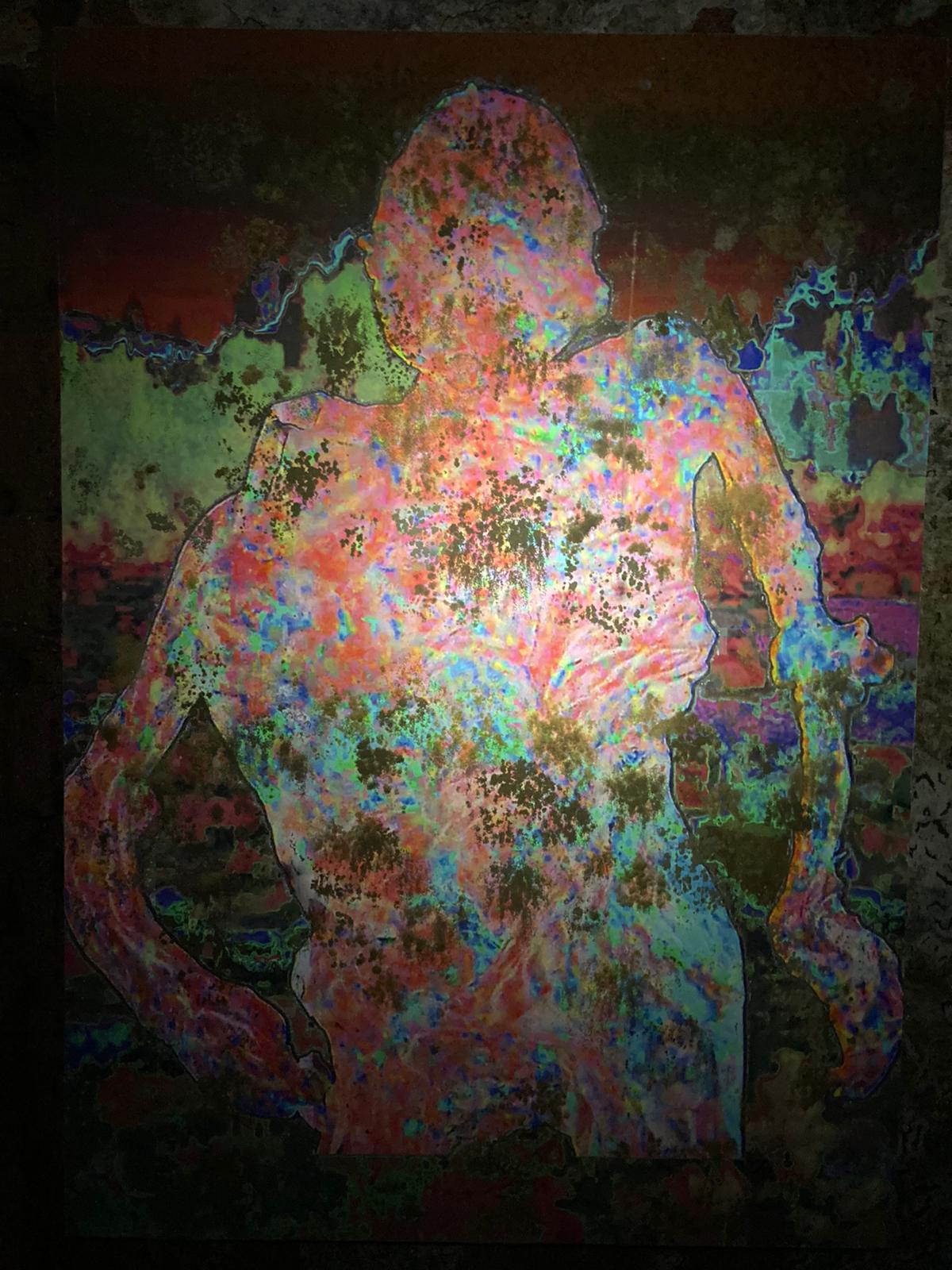

Nevertheless, each piece on show tends toward a comic portrayal of doom, cheerful in the face of its own decay. Faye Hadfield’s gaunt ceramic sculpture Rotten Pot (all works 2021), appears to scream in terror, as though being eaten alive by unseen entities, while Chloe Langlois’s Accursed Underbelly Clown Mystery glares with an unnerving grin as its paper body is digested by the cellar wall. Adam Grainger’s acerbic, psychedelic digital prints Tower and Immortal appear to have already undergone a process of deterioration, a degradation of colour as dilapidated pixels dissolve into chaos. Grainger’s abstractions are suggestive of the webs of membranous mould now enveloping and corroding every object pictured. All works, in fact, seem made in the knowledge that they might not survive, imbued with a self-destructive insouciance that gives them an alluring, sardonic and gloomy intensity.

The unique setting of the cellar provokes questions about anthropocentric supremacy, inhuman agency and art’s relationship with alterity. These art objects don’t seem intended for direct human interaction, only observation from a safe distance. In the case of James St Findlay’s Pregnant Scarecrow the work is explicitly intended for consumption by microorganisms. The belly of this knitted, carrot-nosed scarecrow harbours spores planted by the artist to turn its colourful body into a breeding ground for fungi. Scarecrows, like all dummies, have a potential for animism, as if welcoming possession by some external agent. Each work suggests this same propensity for being taken over, as though they were bodies delivered to the catacombs, little golems waiting to be brought to life by nefarious microbes.

It’s satisfying to witness this flagrant disregard for the traditional notions of preservation that still persist in art institutions governed by art markets and gatekeepers. In the context of the East Midlands, where most exhibitions are made possible by public funding, it’s clear that unsubsidised and unregulated shows are necessary if you want to take risks. International House of Grot denies any ordinary relationship between art, spectator and gallery space. Here, activation of artworks isn’t limited to human participation, but includes moulds, bacteria and fungi, operating in a space that radically questions the symbolic boundaries between object and subject, by privileging direct contact with artworks to non-intelligent lifeforms. The horror may be exaggerated, but the concept of an exhibition where humans just aren’t that important is actually quite unnerving, maybe even a little terrifying. Alexander Mobbs-Iles

International House of Grot is on Instagram throughout 2021 @international_house_of_grot

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here