Gauging spheres of influence and schools of thought is about more than momentary fads – click here to view 2023’s Power 100 in full

And nothing has changed

Everything has changed

The Power 100 list is where, every year, ArtReview exposes, enlists and accounts for the workings of international contemporary art. Not in the usual sense in which ArtReview does this (critical analysis and general commentary about the artworks that are put forward into the world), but rather in terms of the more general infrastructure of the artworld. Why is certain art being made or seen? How is it seen? (And the reversed version of those two questions.) Who decides what is seen? And what, more generally, is the relationship between making and seeing? It’s an attempt to illuminate some of the professionalised artworld’s obscured corners and track its shifts and changes over the past 12 months. It’s also an attempt to chart the reality of an ‘industry’ that can be seen at times to preach one thing and practise another, often making it feel like a world of confusion. Which some would argue is a means of keeping the artworld an exclusive world, but that ArtReview would suggest is (also) one of the ways in which it more generally mirrors the world in which we live.

So, the Power list is a ranking of the 100 living individuals who are shaping art now. Or, more accurately, a little more than 100 individuals, given that some entries comprise groups or collectives. This year all of them are human. (This is not always the case – two years ago a blockchain protocol was at the top of the list; but then again, two years ago most people’s agency was restricted by a nonhuman entity in the form of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns it triggered.)

Making the list is a process – one that involves no small amount of questioning, discussion, bouts of frantic WhatsApp messaging and then going over everything all over again. Who should be where is a subject on which no one really agrees. What makes someone powerful in London or New York is not necessarily what makes someone powerful in Lagos or Kuala Lumpur. Consequently, the end result is often not what anyone imagined it might be at the beginning of the process. Indeed, a quick straw-poll right now might posit some ChatGPT-wielding, AI-spawned avatar as leading the list, given the way everyone is currently losing their heads about the looming threat of artificial intelligence.

But gauging spheres of influence and schools of thought is about more than momentary fads. Art is constantly changing, and the past few years have seen no small number of upheavals. So, when ArtReview came through consulting its secret global panel (they’re secret so they don’t get harassed or bullied, but there are about 40 of them spread globally, and chances are they live near you), keeping tab of references and impacts, debating and rechecking its outcomes, what emerged on the other side was something more surprising, in that a large part of it was familiar: established artists, who have long been around, and their attendant galleries and institutions. Plus ça change?

Though it’s more subtle than knowns and unknowns: at the top are artists who are using their work, and the platform their success provides, to shape communities and push at the boundaries of what making art and sharing it means today, from Steve McQueen’s film about the Grenfell Tower disaster, as a catalyst for legislative change, to Rirkrit Tiravanija’s open-ended interactions, from Chiang Mai to New York, as both an artist and curator, and Nan Goldin’s long-running and increasingly consequential leveraging of her art practice as a platform for wider activism.

In parallel to this is an increased prominence, after several faltering years, of what you might call art’s establishment figures. Four of the people on the current list were on ArtReview’s very first Power List, in 2002 (when ArtReview was a spritely fifty-three). Then, as now, Jay Jopling, Larry Gagosian, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo were on the list (though Pace gallery was also present, headed by Arne Glimcher rather than his son Marc); ten years later, on the 2012 list, were 19 entries still present this year. The presence of these longstanding figures could be taken as indications of a wider consolidation. While the effects of the COVID pandemic are still lingering, the artworld’s established forms and systems are reemerging from the pandemic period, with a corresponding resurgence of the structures and edifices of the art market – its galleries and fairs, and its persistent if somewhat more wrinkled faces, like the Rolling Stones of art.

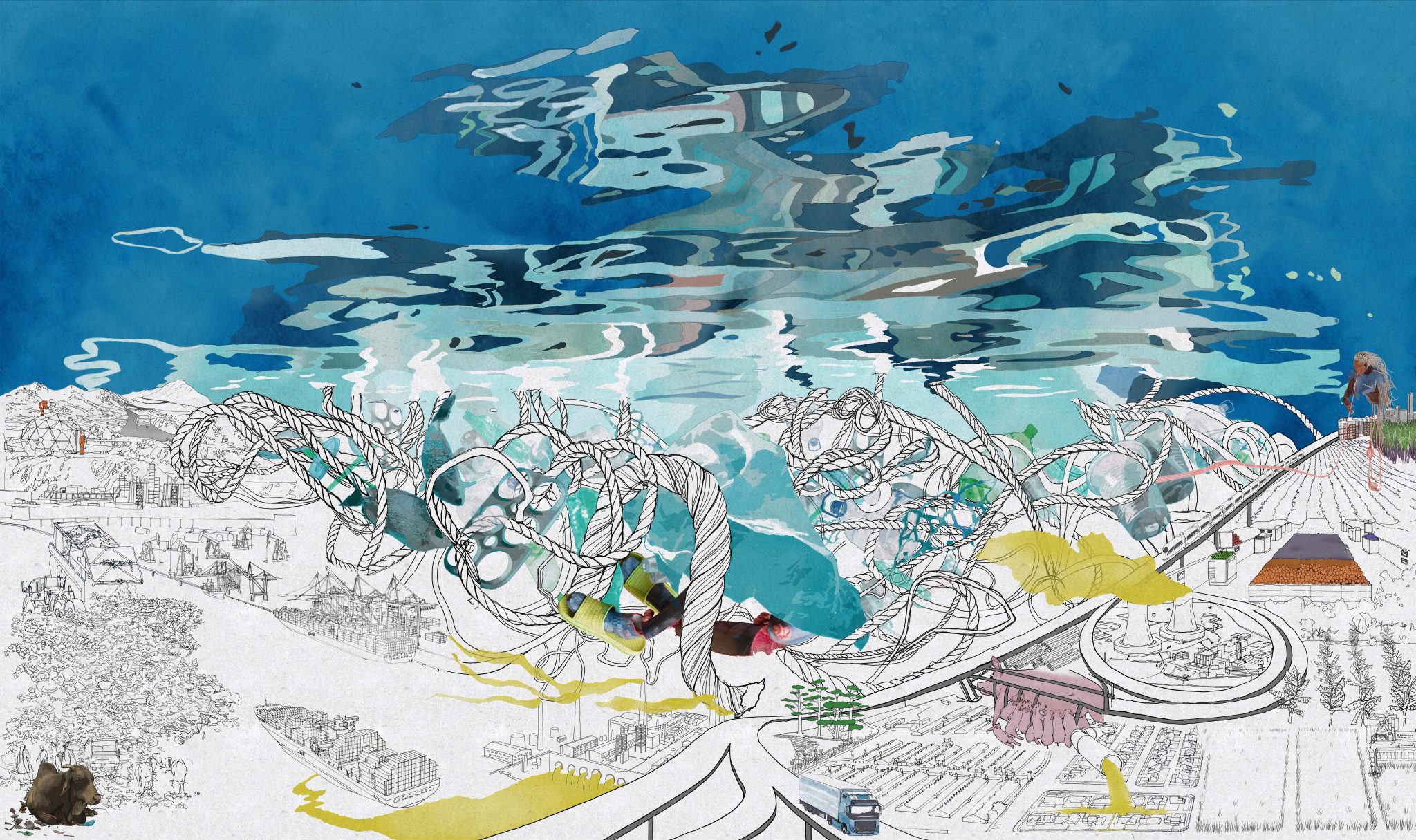

But as ever, there are multiple threads and narratives that run through and overlap in the list. There has been, in recent years, a steady and significant increase of those on the list from beyond the European–North American axis of influence, with art scenes that are finally finding their own voice on the international stage. Running through this year’s list are themes of ecology, Indigeneity and smallscale activism in an unevenly globalised world, and questions about whether or not artists – and art institutions – are able to influence the debates around the important questions of our time. There are, inevitably, contradictions and tensions. The centralising forces of the art market can only exert themselves so far, while art and inspiration might stoke more localised versions of power and agency away from the traditional centres. One important function of ArtReview’s Power 100 is to attempt to map geopolitical conflicts that aren’t about weapons and resources, but about aesthetics and ideas, and how art exists purposefully in a global society, where what happens on one side of the world affects those on the other – whether we like it or not. Back when the Power 100 list began, David Bowie was crooning ‘And nothing has changed / Everything has changed’ on his album Heathen (2002). So while some of the artworld’s long-present power players are here now, changes are afoot. Perhaps among the list now are the coming years’ number ones.