Manuel Borja-Villel ponders the promise of this year’s Venice Biennale to shift the discourse

Operating under the title Foreigners Everywhere, the 60th Venice Biennale promises to be both inclusive and a gesture towards decolonising one of the world’s foremost largescale exhibitions. But is it possible to decolonise a biennial? Can a decolonising discourse radically transform the institution? Venice is more than a thousand kilometres away from the small island near Sicily where Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa set his posthumously published novel The Leopard (1958). Much like Tomasi’s book, could this Biennale be yet another example of a situation in which everything must change in order to remain the same?

It has been well established that many objects found in the collections of great institutions, such as the British Museum, the Louvre or the Pergamon Museum, were obtained as spoils of war. It is also evident that colonialism has changed its strategies over the centuries and that the ways in which domination was exerted were multiple and complex. Frantz Fanon understood the often-invisible mechanisms by which coloniality endured. In his book Black Skin, White Masks (1952) he demonstrated that colonial violence was exercised by making societies believe it was nonexistent. Metropolitan capitals educated the racialised elites of the colonies in such a way that they considered themselves French, English or Spanish above all else, importing the continent’s habits and customs while defending its interests.

Modernity and colonialism have gone hand in hand since their inception. Together they configured a world governed by positivist principles. Any form of knowledge that failed to abide by its codes was considered nonscientific and less evolved than European knowledge, and could even be persecuted as heresy. A modern aesthetic determined how the world was to be perceived and in doing so defined how to inhabit the earth and how to imagine other universes. It established a form of control and laid out the parameters of what could be considered beautiful, good and truthful. It set aside the histories of many populations, eliminating their common narratives and understandings of the earth in one fell swoop. As the scholar Rolando Vázquez pointed out in his 2009 essay ‘Modernity Coloniality and Visibility: The Politics of Time’, modernity imposed two temporalities: one of the colonisers and another of the colonised. The former placed themselves at the centre, in the present, the latter were relegated to the periphery, permanently located in the past. A fracture occurred between these divergent temporalities – between those who dominated and those who suffered oppression.

A walk through the collection at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin is telling in itself. In some vitrines there are visible gaps where masks and sculptures that have been returned to their places of origin used to be. In all of the museum’s rooms the works are now accompanied by contextualising information describing each object’s provenance in detail, specifying if its acquisition was the result of plunder or genocide, or that some of the scholars who wrote on the exhibits were members of the Nazi Party. The impression is that of a thorough and detailed study undertaken for the purpose of reconstructing the biographies of these works. Nevertheless, a question remains unanswered at the completion of the visit: why is it that only the Germans are speaking up? Where are the other voices? This situation is not uncommon for most of the major European museums. Some years ago, the Prado organised an exhibition set to analyse transatlantic artistic exchanges. The title, Tornaviaje (Return Journey), clearly signalled the curators’ point of view: it referred to the return trip of the Spaniards back to Castile. The Indigenous communities were mostly absent from the discourse, as were the Afro-descendants. Despite frequent debates on the need for mending wounds in Europe, there is little awareness that when it is the coloniser who determines who is healthy and who is ill, the wound remains.

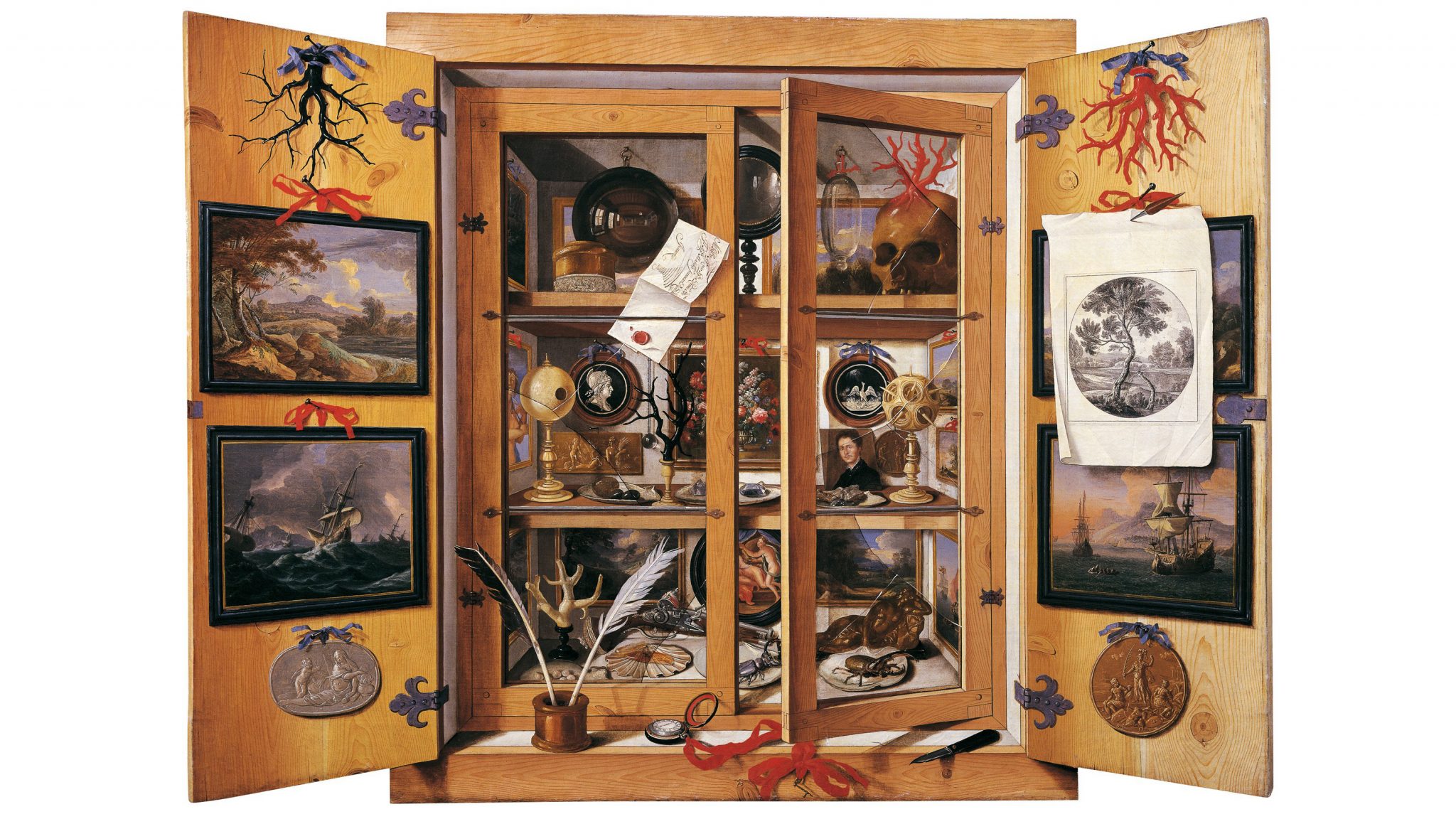

A part of European society is often outraged by the idea of massive restitutions and the resulting losses this would entail for the ‘encyclopaedic museum’, which has granted itself the role of world-heritage custodian for over two centuries. However, any act that is not accompanied by the alteration of our frame of reference is insufficient and ends in condescendence. Stolen goods must be returned, of course. But, even so, if they continue to be displayed and studied at their places of origin in accordance with European ‘scientific’ and universal criteria, they are at risk of losing their enigmatic nature and will remain alienated from those who made them.

The restitution of a treasured item is more than just its return; it is also the regeneration of existing links between the traditions, bodies and lands that colonisation interrupted. It is not a return to the past, but the coming of the past into the present. It brings with it the right to reject Western norms regarding use-value, ownership, access and control. Conversely, it demands solidarity and redistribution. In a process of social justice, it is essential to keep in mind the benefits obtained from the study and display of goods from other cultures and that their return be accompanied by the foundation of shared networks of cooperation and support, so that the colonised are able to create their own institutional forms and develop their own cultural ecosystem. Only in this way is it plausible to close the colonial gap and overcome systemic differences existing between the Global North and South.

It is often thought that decolonisation only concerns those countries with a colonial past. ‘We are in solidarity’ – one often hears – ‘but it is not our problem’, or ‘we have no objects to return’. However, this false assumption is challenged by what Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano called the ‘coloniality of power’. The history of European countries is not independent of the colonies. There is no British or Spanish nation separated from Indian and American communities and people. I am quite sure that the Venice Biennale will grant visibility to some narratives that have been unjustly silenced, if not repressed. Nevertheless, if the people who produced those narratives are denied the possibility of creating their own frames of reference and cannot determine their own forms of governance, then Foreigners Everywhere will remain once more an empty gesture. Decolonisation is a two-way street.

Manuel Borja-Villel is an art historian and curator, and the former director of the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid.