Contemporary art is condemned to newness – or, at least, to its newness. In contrast to the apprentice–masterpiece model of Classicism, and to Modernism’s claim to organise the development of art according to an intrinsic logic tied to historical development, not only is every artist in contemporary art obliged to be distinct to every other (new with regard to everyone else), but each ‘work’ an artist produces has to be different with regard to every other of his or hers. That is: new. As Minimalism and Pop taught us, serial repetition in art is unlike the industrialised mass production that it riffs on, because each reiteration in art is an addition to what has been made before and marks a difference to it in time and experience. Even the direct repetition of precedents is distinguished by the act of reiteration, coupled with the now-standard claims about questioning the authority of the canon. The (near-) identical is something new. In cases where the art looks a lot like other already well-established work, recourse to the inevitably unique biography, history or other circumstantial claim of production (‘the time of labour’) or coming-to-visibility provides the necessary passport to secure access to the required newness. In the best-case scenario, something new can be made of contemporary art on each occasion it is experienced and interpreted (‘each viewing is a re-viewing’). Assertions and defences of what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ contemporary art are all up for debate and part of what makes for being involved in art now – they are only assertions or defences, not truths. Authority over what counts as new in art accordingly devolves from its traditional bases in the artist, the critic, the patron and the museum to instead become a thoroughgoing debate rather than a given. It is a democracy in action.

In this general, broad and systemic endorsement of newness – of its newness – contemporary art is chronically restless. Attached to the present and its passing, contemporary art is definitionally, and somewhat tautologically, the name of all new art that is being made today. As such, contemporary art is wholly amenable to the logic of the update, synchronous with the dynamism of your Facebook and Twitter feeds, as it is to the apparently tempestuous but always insistent movements of fashion, to the social and market advantages of knowing before others, to the mobile insiderism and outsiderism of its irredeemably plastic social scene, to the rapid transformation of the very terms of debate, medium-relevancy and topic. News itself, if you follow it.

And just like the general news, contemporary art makes no overall sense. Committed and bound to the new and all the attendant celebration of singularity and irreproducibility, systemic and general prescriptions for art are ruled out. In this, the chronic reinvention of contemporary art – the interminable and multivalent reinvention that is contemporary art – completes and surpasses modernity’s injunctions to shape anything whatsoever according to current and future needs rather than the sacrosanct bases of tradition, including those of modernity’s programmatic prescriptions.

Distinct from Classicism and Modernism, contemporary art is then an art adequate to the movement of the now in its polyphonic diversity. This perpetual currency of art to its time in general is a great if ambiguous achievement, but it also results in contemporary art’s weird, multiple and paradoxical colonisations of art and history, three of which will be outlined here.

- Art history’s grudging admission of ‘the contemporary’ has come about for two reasons: first, the pressure of students’ increasing interest in contemporary art (as well as the development of rival ‘Visual Cultures and Curating’ departments in universities studying current visual practices in and beyond art) has led art history as a professional field to pay increasing attention to art made now or very recently, thereby incorporating it into the canon constituted by the discipline. Second, the notion of ‘contemporary art’ is backdated to all historical moments, because every art is made in its time. Here, the contemporaneity of contemporary art is taken to be a phase in the existence of all art at its emergence, the immediate circumstances of exhibition and discussion, its impact-in-formation before it becomes a historical object. This makes sense in terms of the discipline if it is to establish a fine-grained, fully historicising account of how art comes to have the orthodox meanings and status it does (as well as the heterodox meanings sometimes proposed by art history itself). The condition such a task assumes, however, is that the standard distinction between the newness of the contemporary (the active present) and the oldness of the historical (a studied past) consequently dissolves – that core distinction of modernity flattening out in an entropic dissolution of history with currency (a flattening convergent with the ubiquitous currency fabricated by the Internet).

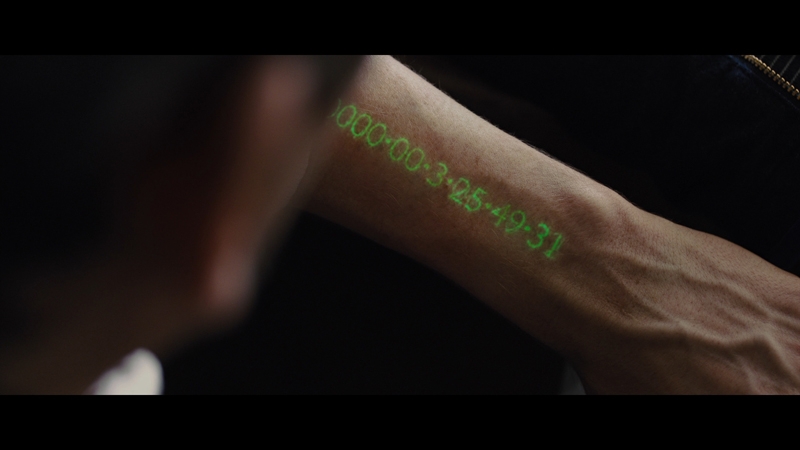

- This growing irrelevance of the distinction between the present and the past is frequently demonstrated in art education, where emerging artists often remake art using strategies and forms similar to those of art since the early 1960s, if not earlier. Contrasted with the postmodernism of about a generation-and-a-half ago, historical work is not taken up here as citation but as a set of permissions, resources and standard formats for current artistic ambitions. Contrasted with the repudiation of the old that is the cliché of Modernism, current practices are not discredited because of their perpetuation of historical art but only if the new work does not differentiate itself in some way, however minor, from its precursor by introducing an additional element – usually something emanating from the artist’s biography or claims about contemporary conditions and urgencies. Taken as an immediate precedent, the historical source is unaged, artistically contemporary in every way to new work, perhaps just with a greater authority. Equally, reversing the equation of new and old, the art-historical survey show is frequently presented by the telling proliferation of museums or institutes of contemporary art in terms of its paradigmatic importance to contemporary practices. The emerging artist is a much-prized consumer of such exhibitions, their interest in the historical survey closing the circle by demonstrating the proximity rather than distance of common concerns and strategies of the work on show. On the other hand, the celebration of the young emerging artist, much vaunted in contemporary art, serves as a much-needed affirmation of this affinity of interests and strategies. Precursors of the art being made now are but contemporaries to it, and simultaneously, art’s spontaneous practice today affirmatively canonises art’s contemporaneity to its time then. Furthermore, contemporary art’s perpetual currency and regeneration are confirmed by its effervescent refreshing of an ever-renewable (which is to say disposable) cache of young artists (a scenario effectively satirised by the generational indistinction and time-buying that is the central conceit of Andrew Niccol’s 2011 science fiction movie In Time).

- The diminishing distinction of past and present under the banner of the contemporary itself corresponds to two leading historical transformations in global political conditions over the period of the 1970s to now, in which contemporary art has become the hegemonic mode of art.

First, as the art historian Hans Belting has elaborated, contemporary art is now a geographically ubiquitous condition of artmaking, establishing a common kind of art that can take place more or less anywhere. It is a ‘global art’ distinct from the traditional category of ‘world art’, which was a Western universalist overview of distinctive arts from di_erent cultures, some of which did not recognise what they fabricated as art. The de-ethnicisation of art in favour of its globalisation via contemporary art, demonstrated on each occasion by the international biennial’s characteristic cosmopolitanism with local flavours, is a consequence of a couple of interrelated factors. On one hand, contemporary art’s emphasis on the now, rather than on school or tradition as the basis for art, admits the relative arbitrariness of the now as the criterion for salience. On the other hand, art today takes the history of art as a usable resource rather than as the unsurpassable authority of tradition’s irrefutably hierarchical asymmetry between the stability of the culture of the past and its current relative ephemerality. That is, contemporary art proceeds by a kind of cultural resource extraction.

Second (and geopolitically synchronous with the emergence of globalisation during the 1990s), the diminishing of substantial difference or antagonism between the now and the then corresponds with the claims made, most notably by Francis Fukuyama, for the ‘end of history’ with the demise of Soviet Communism in 1989. Fukuyama’s claims have their roots in Hegel’s notion of historical progress as the overcoming of contradictions, such that the demise of Soviet Communism and the consequent outright global domination of Western liberalism putatively mark the end of ideological struggles at a world level. Globalisation is built on the consequent common settlement. The ‘end of history’ in these terms does not mean that nothing ever happens again, but rather that all subsequent systemic transformations are variants of the domination of Western liberal capitalism. And while the various countervailing contestations of parliamentary liberalism since the fall of the Soviet Bloc reveal that this diagnosis of the post-1989 condition may be palpably wrong with regard to politics in general, it is fully attained in contemporary art’s easy sliding between the present and the past for its generation of newness. For this reason, contemporary art better realises the promise of the postideological condition that otherwise failed to materialise with the collapse of Soviet communism. For all of the specifics of its particular content claims, that is its overarching political act.

For these reasons, every iteration of art as ‘contemporary’ art is a truly global achievement. Again, it is not that nothing new happens in these conditions: on the contrary, the paradox of art’s ageless contemporaneity – which underpins the colonisations of history, education and world-space just outlined – this ‘timeless time’ that Manuel Castells proposes as typical of network societies, means that contemporary art is characterised by the proliferation of the apparently unconstrained newness that it permits. The sci-fi-horror scenario of Shane Carruth’s Primer (2004) provides a useful analogy here: the film’s conceit is the invention of time-travel that is limited, for technical reasons, to very short times of a few minutes or days. The consequent proliferation of concurrent and proximate pasts, presents and futures corrodes temporal distinction. The destruction of the past by the present – by which individuation, orientation and sense are each time uniquely effectuated, an evisceration that tradition is set against – this ineradicable differentiation wears thin, as then does the difference of the future from the present. That is, contemporary art erodes the systemic transformation of what and how the future of art might be.

For all of their redolence with the paradoxes of time conceived simultaneously in its presence and as a flux, the paradoxes of contemporary art are not however primarily due to its testimony to time but rather to the near-tautology that is contemporary art’s identification with the now. The ageless and smudgy present of contemporary art’s nowness is distinct to the now of time because it is also the historicality of art. Its timeliness marks it out, in a final paradox, not as a category of time but of a durable configuration of art mostly to one side of time’s corrosive and destructive passage. A repudiation of time as the ineliminable and irrecuperable transition from one moment into another, contemporary art’s newness is a holding pattern for the metastable configuration proliferating the kind of art we’re familiar enough with, a genre called contemporary art.

Read New Art Now by Michael North, the first of our series exploring the ‘new’ in contemporary art, from the December 2014 issue.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue.