The largest work in Peter Gallo’s exhibition, Stultifera Navis (2008–11), depicts a creamy yellow ship floating on mostly bare canvas, surrounded by pale flesh-pink and tan daubs of oil paint. The sketchy painting feels like a dream image or a faint memory; it is as if the artist were trying to imagine the vessel into existence. To accompany the painterly touches, the canvas itself seems tattered. It is seemingly constructed from two pieces of fabric, the bottom edge hanging tawdrily down from the stretcher further enhancing the painting’s scruffy nature.

Given that Gallo is based in Vermont and makes his living as a psychiatric social worker in a rural health agency, and given his work’s abject appearance, it’s easy to extrapolate that he is an outsider. His nailed-on canvases, one of them even shaped like Bambi, are slathered with globs of paint in a Band Aid-coloured palette and have all the classic hallmarks of the self-educated naïf. Add to this the unusual surfaces that he has transformed into paintings – among them a skateboard, books, a tabletennis bat, even a large basting pan – and the picture is complete. However, the intensity of his touch belies the knowingness of the artist himself; Gallo has a PhD in the history of art, and in his doctoral thesis, entitled ‘Bio-Aesthetics and the Artist as Case History’, he writes: ‘A central thesis of my project is that during this time artists and their works move into a new bio-aesthetic zone of indiscernability. In this zone, the “living being” of artists, their individualized “bare” or biological lives, enter into new “biographical” arrangements with their artistic production.’ Via Kant, Foucault and others, Gallo’s thesis (available online) o¡ers an ambitious and alternative approach to interpreting art and its history through the embodied presence of the viewing subject, as opposed to a history focused on the iconography of objects.

Perhaps, then, the aforementioned galleon is not just an armature for making painting. Its title alludes to the Ship of Fools, a literary allegory that originated during the fifteenth century about a navigatorless boat of idiots, but also one that, according to Foucault in Madness and Civilisation (1964), may have really existed as a way to cordon off the mentally ill. So are these haptic, playful, James Ensor-referencing objects (one work has the Belgian master’s name painted across a pair of hands rising out of a landscape like a sunrise) dishonest in affecting outsiderness? Or do they hold more weight?

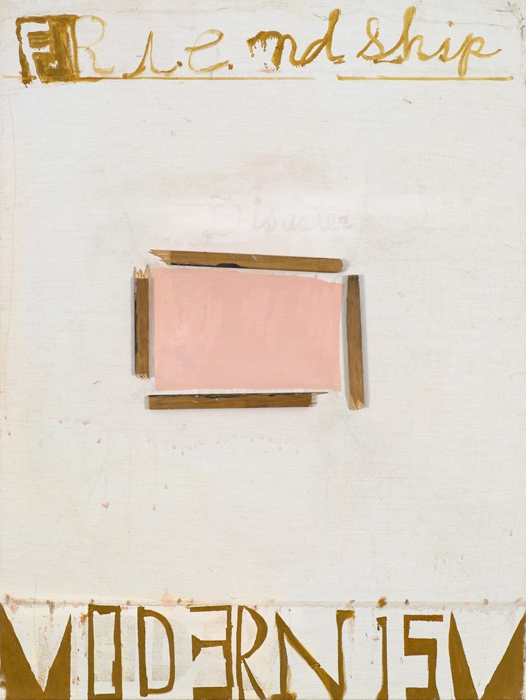

In keeping with Gallo’s biologically themed thesis, the notion of skin is one way to consider these objects. In the argot of the tattoo parlour, skin is sometimes referred to as a canvas, and in Gallo’s case some of his canvases are literally tacked onto the front surface with words painted on them. Certainly words are important; ‘Intifada’, ‘Friendship’, ‘Modernism’, ‘Dreamland Motel’ and ‘She wants stars’ are some of those used, adding sentiment and suggesting memories. In some of the works, this creates a nostalgia in keeping with the object’s careworn nature. Ultimately, Gallo brings together the emotive with the handmade, and this imbues the work with its charm. Just as the viewing body is in the world, his paintings are really objects, things in the world. ‘It is this corporealization’, he writes in his thesis, ‘this embodiment, of artistic identity and experience that I capture under the rubric of bio-aesthetics.’ That is, they seem to be physical manifestations of ideas, ideals or sentiments, as if Gallo were trying to make them real. That, perhaps, is his proposition.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue.