This year’s Taipei Biennial, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud and titled The Great Acceleration, makes an effort to respond to recent theories in science and philosophy. To do this, Bourriaud draws on two key sources: one is a concept borrowed from geological science, the Anthropocene, which refers to the current epoch in which humans and their societies have become a global geophysical force, while the other is object-oriented ontology, a metaphysical movement that rejects the privileging of human existence over the existence of nonhuman objects. Prior to the opening of the biennial, Bourriaud released his notes for the exhibition, as if to till the ground before sowing the seeds of his project. However, the biennial starts for real with a relational work in the Taipei Fine Art Museum’s lobby: Brazilian collective Opavivará!’s Formosa Decelerator (2014), in which people are invited to make and enjoy local tea and to take a break on the hammocks provided – to experience the essence of ‘slowness’ and, conversely, if this attempt is not corrupted by the leisure lifestyle and festival atmosphere that dominates these kinds of event, to reflect on the velocity of contemporary civilisation. It’s an entertaining work that foregrounds the keynote of the biennial’s address: it’s going to be visitor-friendly.

the biennial follows the changing status of nature in the light of artificial materials and translates it into a three-act structure, turning the museum into an archaeological dig

Following this prelude, the biennial unfolds by following the changing status of nature in the light of artificial materials and translating it into a three-act structure, effectively turning the three-storey museum into an archaeological dig that offers prospecting viewers all kinds of materials (the human being one of them) and each participating artist or collective a relatively equal space to ensure a rather complete presentation of each one’s works. And most of those are perfect artistic interpretations (albeit on different levels) of the curatorial subject.

For example, Wu Shanzhuan & Inga Svala Thórsdóttir’s Thing’s Right(s) Declaration (1994) is a series of witty speculations on the rights of objects and a perfect fit with trendy objectoriented ontology (although, compared with those dry, dull philosophical writings, Wu’s text is, as you’d expect, both sexier and more charming). The biennial also showcases artists’ imaginings of the Anthropocene and its aesthetics. For example, a mini solo exhibition of work by Shezad Dawood consisting of a piece of sculpture, four paintings on vintage textiles and a new videowork, Towards the Possible Film (2014): collectively they present a world that is built upon knowledge and visual references from archaeology, anthropology, folkloristics and classic sci-fi films. Timur Si-Qin’s Premier Machinic Funerary: Part 1 (2014) is a ritual scene that creates a calm, clean, semi- NASA / semi-Zen atmosphere, in which the artist has transformed the material being of a distant human ancestor (a male Paranthropus boisei who lived around 1.7 million years ago in what is now Kenya) from organism to digital data, then synthetic, through 3D-data and printing technology.

Bourriaud points out in his notes that The Great Acceleration is presented as a tribute to the coactivity of the human and nonhuman, the assumed parallelism between them, and their negotiations. However, certain works offer alternative voices. For example, as a response to Bourriaud’s emphasis on the collapse of the human scale and a new type of ‘ghost dance’ in the age of the Anthropocene (subjects become objects, and objects subjects), Taiwanese artist Po-Chih Huang, in his Production Line – Made in China & Made in Taiwan (2014), manages to rebuild a live production site, in which workers’ names and stories are written and told, thus bringing what is, in terms of manufacturing these days, generally metahuman to a ‘human scale’.

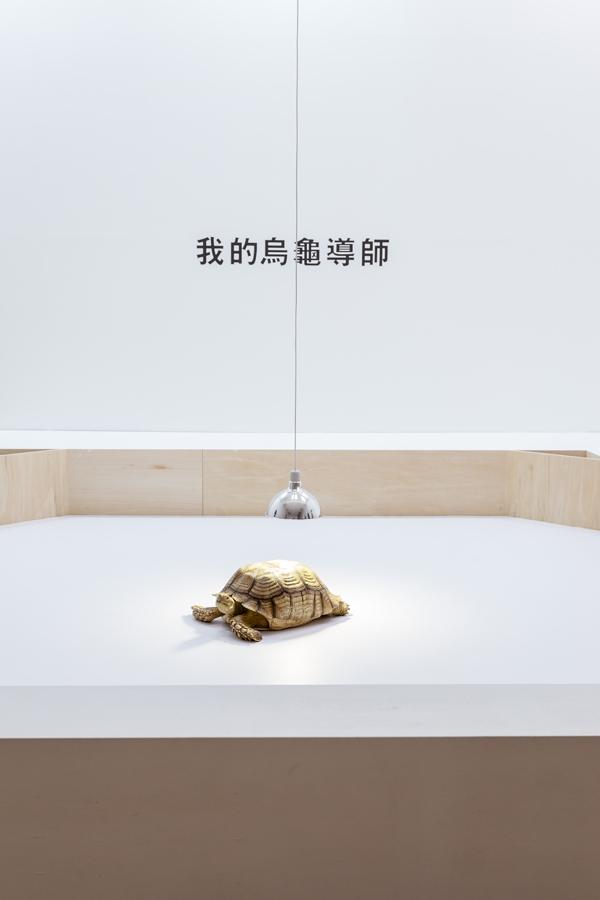

In contrast to Opavivará!’s for-the-occasion tea ceremony, which appears to be entertaining, celebrative and lifestyle-esque, Shimabuku’s works always express his negation of some of today’s most popular values. My Teacher Tortoise (2011/14) offers a real tortoise living in the gallery, to inspire people to consider the benefits of staying still (with ‘stop / stop and think / return / occasionally run’ printed on a poster). Mobile Phone and Stone Tool (2014) shows how one of the more recent technological inventions of humankind is similar to a tool from the Stone Age. Yet these works should not be categorised alongside many of the others in the biennial that are presented by Bourriaud as a tribute to the coactivity of human and nonhuman, because in Shimabuku’s art, humour, human emotion and human behaviour (all as di¡erent expressions of ‘human scale’) always play a major role.

In general, The Great Acceleration is, in a simple, direct way, easy to digest, though some people may expect it to be more intensively presented. While Bourriaud provides an interesting viewpoint on the world and a new relation between every different kind of ‘thing’ or different scales, most of the artworks that he has selected tend to be either a literal or an illustrative interpretation of the biennial’s subject. In a way, Bourriaud’s The Great Acceleration and Luc Besson’s 2014 film Lucy (partly filmed in Taipei) might be seen as two variations of one story: some great, uncontrollable acceleration (caused in the film by a synthetic chemical substance, CPH4) has broken the boundary between the human and the material world, thus changing the human view on everything.

Furthermore, viewed in a new way, the world no longer works under the same old ‘universal’ rules, therefore ultimate concerns such as the start and endpoint of history (a very typically Western thought, derived from the linear concept of time, though Bourriaud stated previously that he would take the opportunity in Taipei to trigger a dialogue between Western and Asiatic philosophy) and the universe are pursued. Besson’s Lucy doesn’t tell a convincing story, but the visuals, performances and rhythm of storytelling are first rate. The Great Acceleration spells out Bourriaud’s new grand narrative in a static, archaeological way, but does allow the voices of individual works to provide their own commentary.

Last but not least, if we agree with the accelerationist vision described by Bourriaud, the compound sculptures created by Sterling Ruby and his contemporaries – though what Ruby is showing here is a series of his early nail-polish paintings – will become the symbolic visualisation of humanity’s imagination of the material world of the future. No wonder the production design of the future supercomputer in Lucy is so ‘Sterling Ruby’. The last time that people saw such a revolutionary and symbolic visual so widely distributed was in 1999, when the first poster for the Wachowskis’ The Matrix was released.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue.