Editor’s note: On the occasion of Akomfrah’s first American survey exhibition, Signs of Empire, opening at the New Museum on 20 June, ArtReview republishes a profile of the British filmmaker, from the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.

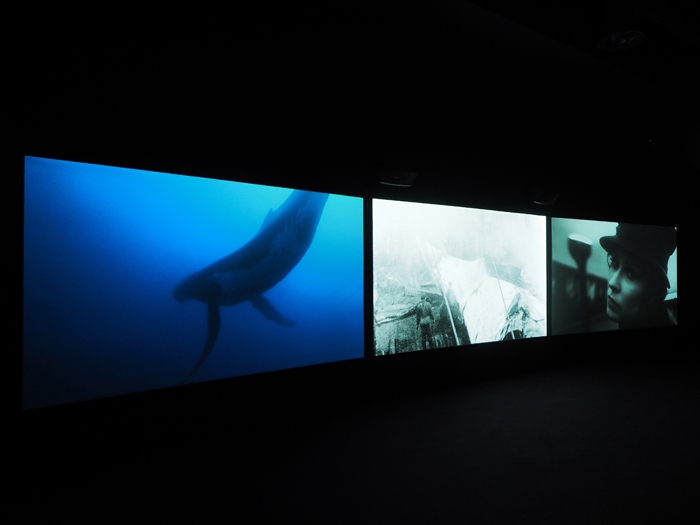

Among the standout works in Okwui Enwezor’s All the World’s Futures at last year’s contentious – and occasionally overwrought – Venice Biennale was experimental filmmaker John Akomfrah’s subdued cinepaean to the ocean, Vertigo Sea (2015). A 48-minute, three-screen installation bringing together material sourced from thousands of hours of archival footage, screened alongside various austere, Victorian-inspired tableaux of the littoral, Akomfrah’s film explores a difficult range of histories – from whaling, nuclear testing and deep-sea executions to the recent Mediterranean migrations – all under the heading of what he calls ‘oceanic ontologies’. On view through April at Bristol’s Arnolfini for its UK premiere, Vertigo Sea has been released in combination with a career-long retrospective of Akomfrah’s work at Lisson Gallery, London, both of which highlight the auteur’s sui generis image-making of political identities.

“There’s a little-known biographical detail,” he explains when we begin discussing the particular origins of Vertigo Sea, “which is that I almost drowned twice in [the ocean] as a kid. Once, just escaping, because someone saw me at a beach in Accra being pulled under and swam out and got me. So, in the back of my mind there’s always been this reverence and to some extent a fear of that space.”

It is this acute attention to collective memory and the personal – traits that have imbued all of Akomfrah’s work, beginning during the 1980s with the avant-garde Black Audio Film Collective (BAFC) – that elevates Vertigo Sea from mere wildlife documentary to a dense, philosophical meditation on eco-poetics and the posthuman condition. Echoing something of Peter Sloterdijk’s recently translated Spheres Trilogy (originally published in German, 1998-2004) – which uses images of the bubble and foams as phenomenological leitmotifs – and Martin Heidegger’s post-Being and Time (1927) essays on ecology, Vertigo Sea builds upon the contention that the story of globalisation, in both its political and geographical connotations, commences with the sea and the utopian urge to bisect and ‘conquer’ its frontier.

“Even in conventional understandings of settled identities, one should at least acknowledge that one arrives at this epistemological or ontological idea of settlement by engaging in the process of flight to the other,” Akomfrah explains of the film’s metahistorical roots. “… [T]he ‘here and there’ were intimately bound up with each other.”

It’s also this vast, philosophical speculation about aquatic space, and the way in which that space [poses] questions of mortality, of becoming, of relativity, the demarcations of human and nonhuman

Interspersed over Vertigo Sea’s soundtrack of burbling spume, news reports and whale songs are bardic recitations of Friedrich Nietzsche and Heathcote Williams, as well as Herman Melville’s transcendental seafarer’s tome Moby-Dick (1851), which supplied the project’s initial, ecological springboard. “It’s sold to you as a novel, and of course it is a novel,” says Akomfrah. “But it’s also this vast, philosophical speculation about aquatic space, and the way in which that space [poses] questions of mortality, of becoming, of relativity, the demarcations of human and nonhuman. And, of course, the coming of multicultures and how they are formed. All of these are the speculative shape of Moby-Dick… There’s a discursivity to it, of those protean forms and shapes that most authors get into over 10 or 20 novels.”

Vertigo Sea’s thematic emphasis on Melville’s urtext on the American colonial imaginary also complicates what might be assumed, at least initially, to be a film directed towards the more doctrinaire tenets of postcolonial Marxism. Certainly Vertigo Sea’s numerous images of vivisected whales, brutalised West African slaves and migrant corpses littering the Greek shoreline epitomise some of the most heinous atrocities committed by the West under the aegis of Empire. But Akomfrah’s knotty portrait of sea life, of whale and whaler, slave and slave-trader, is neither completely romantic nor intransigently macropolitical. Rather, he frames its contents, and actors, as bound by a certain utopian resolve within an oceanic ontology – a frontier of the human oikos in which identity formations are determined by continuous diaspora and what Akomfrah calls the sea’s “mesh of rhythms and mortalities”. It is not surprising, then, that he will partner Melville’s incantatory Liberalism with the speculative poetics of Williams’s Whale Nation (1988): ‘Free from land-based pressures: / … Larger brains evolved, ten times as old as man’s… / The accumulated knowledge of the past; / Rumours of ancestors, / … Memories of loss’.

“If you say you’re interested in formations of identity, and those formations of identity could be either of the racialised or sexualised or gendered variety, then at some point the space of the aquatic binds certain subjects together,” he explains. “So how does one find a way to talk about the Vietnamese drowning at sea in their thousands in the [19]70s with political prisoners being dumped at sea by both the French in Algeria and the militant junta in Argentina? Once you start to connect those things, you begin to think that if a politics of identity as opposed to ‘identity politics’ has any value then surely at some point it might be important to dwell on the question of sentience itself as a kind of register.”

This acuity for metahistory is reflected in the film’s various intertitles, which jump from fifteenth-century Newfoundland to 1970s South Asia, an ambitious trek made all the more profound by its recurring allusions to the current Libyan sinkings. No doubt part of the present European immigration crisis stems from a First World state of amnesia, Akomfrah contends. A condition that owing to its urban complacency amid schematic transportation technologies has ceased to acknowledge the embedded cosmopolitan impulse of the human to move, escape and resettle.

Akomfrah’s focus on events, themes and characters of the African diaspora originate with his cofounding in 1982 of BAFC, which included current collaborators Trevor Mathison, David Lawson and Lina Gopaul. Akomfrah, himself, had fled with his mother to London from Ghana immediately following the country’s 1966 coup, and his own experiences of both migration and multicultural identity informed the collective’s aim to merge a black, British urban politics with a radical, modernist aesthetic. The latter was, for the aspiring director, represented in the filmworks of Dziga Vertov, Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Eisenstein, among many others, which he first encountered while studying sociology at Portsmouth Polytechnic.

Akomfrah’s first directorial feature with BAFC, Handsworth Songs (1986), chronicles the riots in that area of Birmingham with just such a hybridity of social realism and formal experimentation, displaying ‘the serene confidence of its experimental essayism’, according to Mark Fisher, writing in a 2011 issue of Sight & Sound. ‘Instead of easy didacticism, the film offers a complex palimpsest comprising archive material, an empathic sound design and footage shot by the Collective during and after the riots.’ Subsequent films like Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993), The Last Angel of History (1995) and Riot (1999), many of which were broadcast on Channel 4 as the last vestiges of ‘workshop’-era cinema, followed a similar experimental structure, combining assiduously researched archival footage with formalist interventions of sound, elliptical storytelling and dramatic reenactments.

The end of the BAFC in 1998, however, marked a distinct shift in Akomfrah’s aesthetic, one that would turn away from what critic Brian Winston calls a ‘Griersonian’ model of empiricist documentary towards a utopian ideal, in which explicit questions of place-ness, nomadism and posthumanism would take precedent. “I think the urban paradigm was eating itself as a cliché,” he explains. “Because I just felt it was necessary to try and avoid this kind of cul-de-sac we could potentially find ourselves landing in. You want to find another way of coming at the same questions or even ask yourself different questions… [And] part of it is this turn from the dystopian scenarios of Last Angel, for instance, to the utopian scenario of The Call of Mist” – alluding to his 1998 short film that meditates on the death of his mother alongside topics like cloning, technology and landscape.

The Call of Mist and Memory Room 451 (1997) also signal the filmmaker’s deployment of neo-expressionist tableaux and a saturated, digital colour palette. Their focus on narrative and phenomenological abstractions, blending rich chromatic sequences with references to various memories, dreams and myth-structures, anticipate Akomfrah’s Romantic figurations of liquid and other natural ecologies, which come to supplant the dominant urban topos situating most of the BAFC projects. Similarly, The Nine Muses (2012), perhaps Akomfrah at his most densely literary, pairs extensive footage of the Alaskan tundra and English Shires with bricolaged recitations of Homer, James Joyce and T.S. Eliot to evoke a sense of the sublime in the perambulatory histories of migration and settlement. “Underpinning all of that is a deeply felt need to return to some ‘big questions,’” he concludes. “And to pose the question of identity inside those larger questions of being and becoming.” For Akomfrah, the human is not only a rational animal, he is also an assemblage of climates, cartographies and languages, both inhabiting and resisting the territories across which he ceaselessly moves.

As the consummation of this intensifying eco-poeticism in his filmography, Vertigo Sea shifts the conventions of social documentary from the purview of the human agent to that of the earth, exploring an ontology in which global man is placed in service of the sea. Its rich, aqueous panoramas, spread from screen to screen, remind us of Whale Nation’s closing verse: ‘From space, the planet is blue / From space, the planet is the territory / Not of humans, but of the whale.’ In capturing this world, Akomfrah reorients the possibilities of identity politics from conventional sociocultural categorisations of race, gender and sexuality to a politics of being itself.

This article was first published in the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.