In stories, pirates bury treasure. They lock it in chests and drop them in deep sandy pits to conceal their overflowing booty of doubloons and gemstones; to hide it from the light that makes it glint so promiscuously. But in the main these are just stories. Often about how these vast riches vanish back into the earth, as if the ground itself had swallowed up all trace of value, returning human wealth to the geology from which it came. Ashes to ashes, and all that jazz. But in London right now there’s another kind of wealth being buried: giant pits dug beneath the homes of the wealthy into which very twenty-first-century forms of surplus capital are concealed – vintage cars, art collections or simply vast, newly created expanses of prime residential square-meterage.

They are called iceberg homes, these London residences of the megarich. For like icebergs, only a little shows above the surface. But in reality they are something far stranger. These are not buried homes, but camouflaged decoys that form an entirely inverted skyline, an invisible cityscape

of voids that lurk beneath. The latest to hit the headlines is Damien Hirst’s Regent’s Park mansion, a John Nash-designed Grade I-listed building bought for a reported £34 million in 2014. Not content with 14 bedrooms over five storeys, Hirst has obtained planning permission to demolish a gardener’s cottage and replace it with a new portal to a vast underground private art store.

Hirst faces the same problem as others among the London megarich: the possibilities of wealth are constrained by planning regulations. The exterior character of these residences can’t be changed; they can’t be built higher, and they certainly can’t be razed. So with the only way down, engineering and machinery are deployed to mine vast quantities of habitable space from the depths of London soil.

These huge holes are transformed into subterranean extensions – extensions in area and to the very concept of domesticity. Lakshmi Mittal, the Indian steel-magnate, has a jewelled subterranean swimming pool in his Kensington home. A residence at 21 Grosvenor Mews has a car lift, garden with sliding roof and, through the entire height of two aboveground and two subterranean storeys, a decorative nine-metre interior ‘waterfall’. In Holland Park, under a Victorian villa, is a 25m swimming pool, entertainment room, wine cellar, cigar room, massage rooms, two-level gymnasium, dance/yoga studio, hot tub, sauna and steam rooms. You get the idea.

In each, the historic London typology is entirely eviscerated. The heritage (and legally protected) outer casing remains intact, but its innards are (often) scooped out and dumped. Inside, an entirely new idea of living is constructed. Like ‘grow houses’ – those suburban homes transformed into marijuana farms – the exterior of the house remains only as camouflage for an entirely different kind of interior.

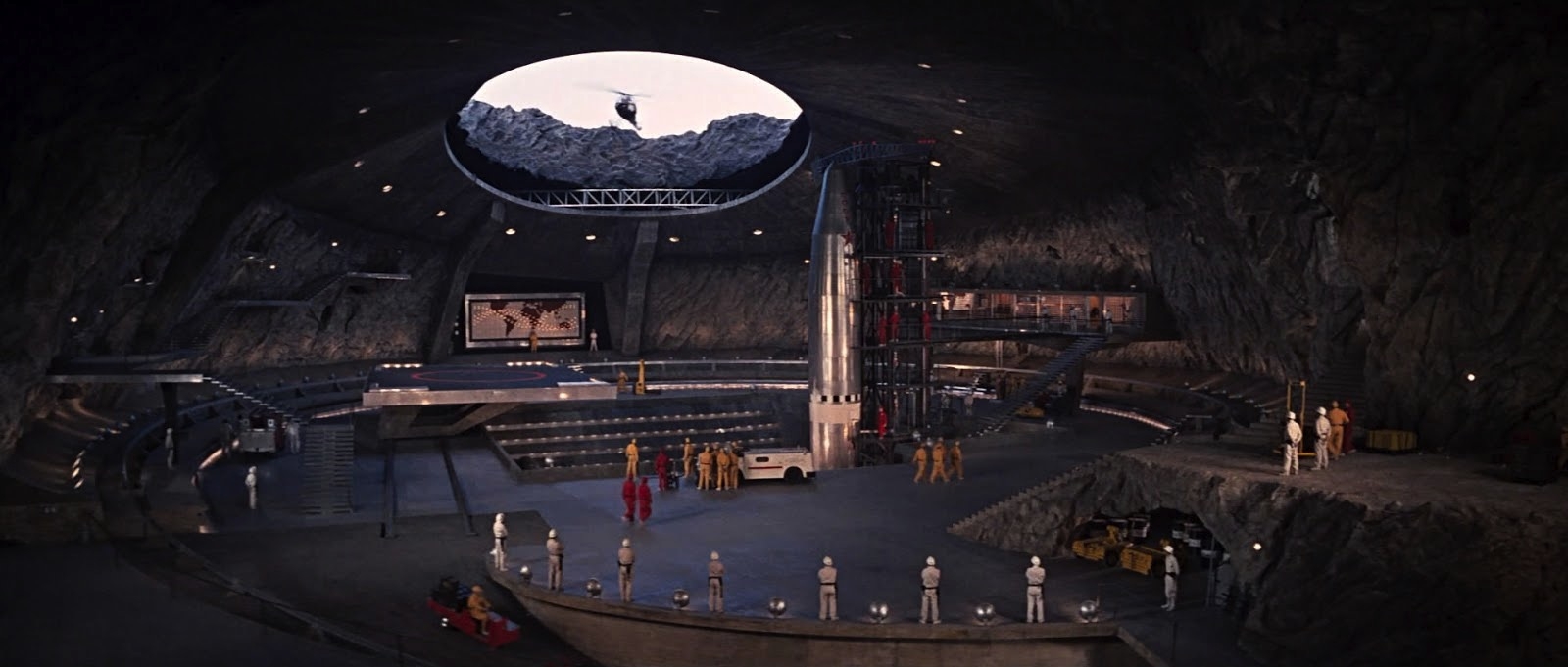

We could also pursue other psychological avenues. Iceberg homes are more bunker than house. Their gaping holes may be filled with luxurious programmes and lined with the fabulous glister of exotic materials, but they are entirely private worlds. Their typology is related to infrastructures of defence. The world of the superrich is paranoid, characterised by extreme power and extreme vulnerability. The world belongs to them, but is also the source of innumerable threats to their existence: of violence and robbery, of regulation and taxation, of revolution and regime change. Digging down exercises the power to create a new, secure, private world.

In this sense, these spaces are nothing less than cavernous panic rooms, a place to retreat from the threats of the aboveground world. It’s no wonder that these fantasies of extreme liberty and total fear resemble the underground lairs of cinematic supervillains.

But what these homes show perhaps most of all is the meaning of wealth in the twenty-first century. For storybook pirates, wealth was material. It was mineral and metal, made valuable by its scarcity. But wealth now has become something far stranger: immaterial digits, disembodied signifiers of value that float through networks cut free from physicality. And in turn, what we see in these iceberg homes is the pit – for pirates, the mechanism of concealing wealth–transformed into the thing of value itself. The hole is the treasure, the void is the ultimate product of riches beyond our wildest dreams.

This article first appeared in the January & February 2016 issue of ArtReview.