The artist’s nonmonumental assemblages conjure icons that are all-too-human: fallible and beyond salvation, perhaps. Who needs salvation anyway?

It’s a still winter’s night in Berlin and I’m on my way to meet Jesse Darling in their studio. But I’m having trouble finding it. I go to the wrong red entrance and make several circles before eventually discovering the word ‘Darling’ handwritten on a doorbell. I press my cold finger against the colder silver disk and hear a muffled voice. I’ll come down. Tony (my dog, now aged one, procured during a moment of lockdown loneliness) gleefully jumps up as Darling opens the door; a gentle hello in response; their soft jumper with fluffy arms its own kind of animal.

As an artist concerned with the body in space, its inherent vulnerabilities and contiguous failures, Darling’s primary medium is sculpture. Comfort Station (2017), for example, is a bedside commode that has collapsed, crawling on steel and aluminium limbs that are bent out of shape; or there’s A Fine Line (2018), a steel-core washing line from which the intimacy of a domestic life is hung out to dry – baby clothes, used shoes and tea towels as assorted commodities interspersed with barbed wire, all blowing in the breeze of a fan. This is Darling’s wry acknowledgement of the ongoing crisis of life under capitalism, their sharp commentary on the violence of petro-chemical modernity refuting the myth of progress: “I think about modernity as a fairytale,” they explain. “It’s a thoroughly arbitrary and weird situation that starts with the first colonial excursions in the 1700s – depending on where you begin – or the Inclosure Acts, and goes all the way up to now. Capitalism, modernity and white supremacy are all part of the same story. Because I grew up in that church… it seemed like this is how things are, but this is not how things are, it’s just how we’ve grown up and been educated… Progress and growth are lies used to justify violence.”

Their show at Modern Art Oxford – Darling was born in Oxford – No Medals No Ribbons, includes signifiers of the damaged or disabled body, sometimes enhanced by prosthetics or machines. In a cultural moment where identity politics is at the forefront of discourse, Darling’s work is regularly read through the lens of biography – like that of many people who aren’t cisgender white males – citing their gender, disability, lovers and personal life. However, Darling emphasises that they are working towards a nonmacho sculpture practice shaped by making objects in narrative formulations. “I want to change the narrative and give the works the chance to show up in the one space, according to their own merits, on their own terms,” they explain.

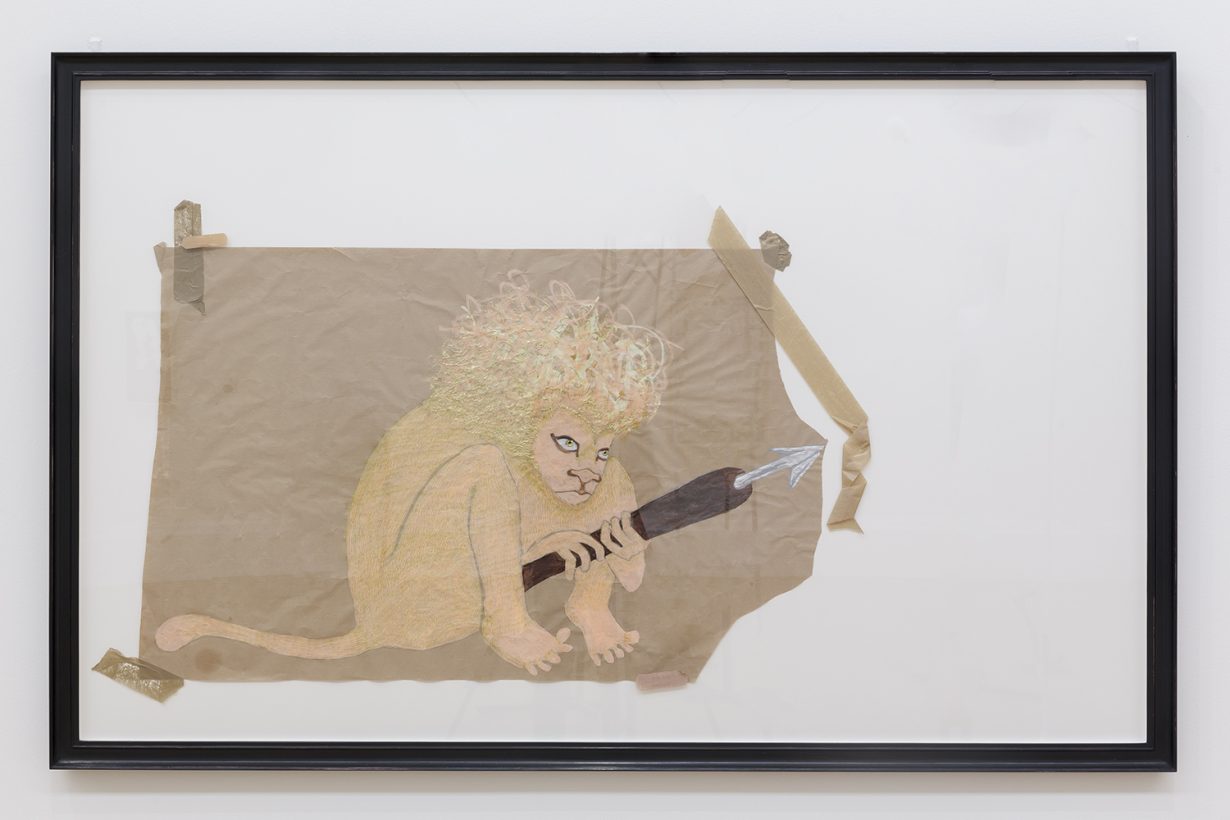

In their studio, Darling pours Tony and me respective receptacles of water, and then uses a spray bottle to hydrate the clay body they’re carving. Headless, it is modelled on a porcelain doll, with gently curving shoulder blades and an exquisitely rendered spine. Darling’s interest in the human form sees it as neither perfect nor imperfect, the saintly or godly collapsed into the mortal, which chimes with how they say, “I’ve been thinking about storytelling for a long time”. Indeed, it directly underpins their ongoing references to myths or ecclesiastical stories of saints. Take their drawing on ripped brown paper secured with plasters and mangled parcel tape, Lion in wait for Saint Jerome and his medical kit (2018), in which a lion crouches fearfully upon a spear, longing for Saint Jerome (the story goes that when confronted with a ferocious lion, the saint acknowledged its pain, removing a thorn from its paw and gaining lifelong comradeship). Depicted with lustrous gold locks, the lion has its own sacred aura, suggesting dignity not in the divine but in the broken or fallible. It is as such that Darling tackles the question of faith and fetish, relieving saints of their halos and bestowing them on the living, the strictures that bind bodies given a new logic or validity.

Humans are all always telling stories: factual, fictional and the in-between. They are a way of making sense of the world through our relationship to that world. Sometimes stories are vocalised by tongue and lips; sometimes they are scribbled; and sometimes they are expressed by objects, held as matter shaped by hands. We tell ourselves stories in order to process what happens to us, but we too are bound by stories imposed upon us. And it is in this sense that Darling is interested in what has been told, could be told and should be told, why and by whom.

At Modern Art Oxford, the artist says, stories are articulated through “fairytales and votives and tabernacles and dysfunctional machines”. Certain themes or images keep emerging through the exhibition, including crucifixes, aeroplanes and flowers, which speak to states of fragility or the contingency of the subject under capitalism. New and existing works from the past decade, including installation, drawing, sculpture, video and text (an aside: in 2021 Darling published VIRGINS, their first collection of poetry), seek a space in which the notion of fixity or certitude is not only irrelevant, but also ontologically impossible, by prioritising a sense of precarity. Twisting and turning and curving, Darling’s work is a generative network of associations that are intentionally “jumbled up together and messy”, and ultimately boldly disquieting.

Initially grouped with the postinternet movement – in which artists often made work that framed the internet and social media as a democratising tool that overturned the world’s hierarchies – Darling’s works sometimes included several screens and projections with pixelated videos. Not least because of the algorithmically defined rise of the alt-right and white-supremacist patriarchy via this once ‘utopian’ space, they have subsequently focused on making sculpture with low-cost, everyday materials as far ranging as ring-binder files and pillows, mobility cranes and strap-ons, while also welding and working with clay and jesmonite. Shown at Tate Britain with The Ballad of Saint Jerome in 2018 and the following year in the 58th Venice Biennale, Darling’s works have been characterised as wounded or unsteady over the past few years. Take the gaggle of characters in March of the Valedictorians (2016) – red plastic school chairs with long, lanky welded steel legs warping and stumbling as one towards graduation, or Sphinxes of the gate (2018), which sees two of the mythical beings encased in glass vitrines, jesmonite faces affixed to a bare skeleton armature, one bound with a gag, the other sucking from some kind of surgical catheter bag.

Their nonmonumental assemblages conjure icons that are all-too-human: fallible and beyond salvation, perhaps. Who needs salvation anyway? Saint Batman (2016), included in the show at Modern Art Oxford, comprises a bin bag for a body and a pink antivirus mask for a mouth, plugged with a sugary lollypop. The saint hangs on a welded steel cross, crowned with a halo of ivy. For Darling, “everyone is failing and dying and fucking up. Everything is, everything will. Nothing is going to last or get out of here alive. There’s no pure place, there’s no utopia, there’s no time in the past or the future when everything is just beautiful. It doesn’t exist.” And it’s in this spirit that this Batman is saintly with imperfection, a mortal trying to navigate the mire, finding a way to exist, despite it all. Darling further reflects, “Maybe that’s what I’m trying to do: mess around in the subconscious of petrochemical modernity. You find all this extremely perverted, goofy, loveable, absolutely violent wild stuff in its subconscious.”

Other works in No Medals No Ribbons are placed in such a way as to complicate readings, associations becoming ever generative. A set of objects, which together create a scrambled index of references, includes the figure of a foetus next to a plastic bag; a Hitachi magic wand held like the Statue of Liberty’s torch, suggesting a human’s body buzzing with the full force of the electrical grid when this famous sex toy is plugged into the mains; some things that are queer-coded through specific characters and then other things that aren’t, so that you never really know what you’re looking at, a purposeful strategy to evade singular or definitive stories. Darling’s is a lexicon that won’t be pinned down.

While Darling does not use scale in a monolithic sense, the exhibition’s largest work, Gravity Road (2020), expands into space as a vast anthropomorphic rollercoaster. The sculpture visualises the relationship between gravity and buoyancy, steel tracks that rise and fall, undulations giggling over sweeping bends. It has legs in three places buckling under their own weight and two outstretched poles that double as arms (reaching for embrace?). While on the surface, rollercoasters are indicative of fun, Gravity Road speaks formally to the history of the mining train, channelling stories of extraction, exploitation of labour and the locomotive in the context of industrial capitalist gain, as well as to automatisation and technologies that reduce human intervention in manufacturing and labour processes. Darling describes how “it was joyful to make” because of the hands-on physicality of building something by eye, without drawings, measurements or plans, without “symmetry or precision” – the rollercoaster’s inherent alignment with pleasure-seeking seeping in. As a metaphor for the long curve of modernity, Darling has created their own monstrous dinosaur skeleton to channel “the full awe-fullness, horror and glory” of our petrochemical constitution today.

Conflating the museum with the mausoleum in their epistolary text for Gravity Road: A Rollercoaster Reader (2022), a forthcoming publication, Darling sees it as a space holding ‘dead’ objects that are elevated to sacred status. Indeed, they cite the museum’s ‘evolution of the fetish, a concept invented by the colonial anthropologists to justify the violent deterritorialising theft of objects and artefacts’. With a methodology that counters colonialism’s logic of decimation, ‘ripping worlds out of worlds’, Darling combines materials as a catalyst for the creation of worlds out of worlds, formulations that, rather than cleaving, open up possibilities. As a set of material relations, these generate futurities and multitudes in a process of thinking, being and – perhaps most importantly – becoming.

Considering the so-called universal and what could possibly bind us in a collective experience, Darling emphasises “everyone’s contingent position relative to everything else and their own messiness and morality: that’s the only ‘we’ that we can talk about”. No Medals No Ribbons aims to ask in what means systems of power harness and attempt to control such messy contingency, and how in reworking or reenvisaging how malleability, asymmetry and even fragility function they might become proponents of resistance. Such approaches look for expansive and unfettered subjectivities, chiming with a verse from Darling’s poem ‘After St Agnes’:

I tell you what, let’s us play Eden.

I’ll be the snake or I can be Adam.

You can be Eve. No –

you be the garden.

After all, there really is no singular straight path that can be pinpointed. As Darling says, “There are only cycles of life and death.”

Jesse Darling, Enclosures, Camden Arts Centre, London, 13 May – 26 June 2022