The interstellar adventure plays beautifully with the vastness of the cosmos, while struggling against the confines of its toy-like alien planet

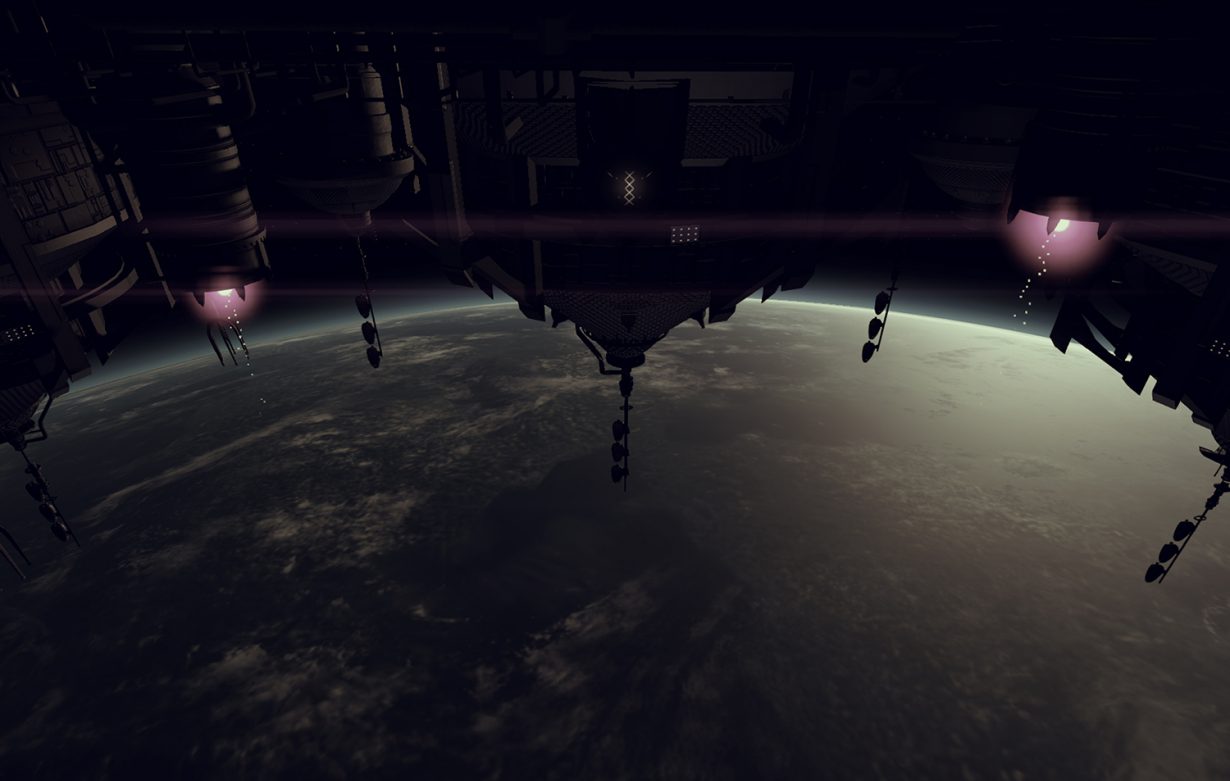

A tiny, fragile, glinting ship, crossing the surface of an alien planet, so vast we can perceive the curvature of the horizon. It’s an image that within science-fiction has been overplayed almost to oblivion. It’s hard to think of a spacefaring fiction that doesn’t take the requisite moment to make this shift of scale (think of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s(1968) docking sequence, Prometheus’s (2012) planetary descent, or the classic science-fiction book covers of Chris Foss and John Harris), leaping out to show the characters’ vessel against some otherworldly landscape or nebula. Jett: The Far Shore (2021) makes a whole game from this image, and in doing so unfolds its possibilities and resonances, ultimately to both its credit and detriment.

Jett is the second game from the studio Superbrothers, whose Sword & Sorcery EP (2011) was a break-out success on iPhone and iPad, seemingly despite its understated and unusual art-game atmospheres, which marked it out from other popular App Store games of the same era. It would help establish Apple’s smartphone as a home of unusual, experimental and pristinely designed art games. Jett is the difficult second album then, long in development and carrying a significant amount of pressure and anticipation.

Jett, both in its earliest moments and its strongest sequences is an experience that engages with the ambient possibilities of videogames. Its opening sequence, beginning on the home planet of an unfamiliar human society, takes you from a windblown steppe across a sepia ocean to a pseudo-religious cosmodrome, where chanting crowds, backed by a chorus of smokestacks and refineries, buoy you onward onto an interstellar voyage. Balanced between intimate, weighty sequences of first-person walking and weightless, horizon-chasing, flight in the titular Jett aircraft, the game confidently builds enveloping atmospheres out of stark, disorienting, shifts in scale.

Scale is vital here, as the plot revolves around a project bigger than any of its parts, where tunic-wearing characters speak in teleological terms about the great project of space exploration they are undertaking, marked more by their sense of walking in history than they are by their own personal experience. The obvious reference point, both thematically and aesthetically, is the Soviet Union’s Cold War era space-programme, and the way it reimagined the socialist project beyond the confines of Earth’s gravity. But Jett feels secondary, distant, in its references here, evoking more the utopic and generalised space-socialism of a novel like Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974), than the history of Soviet cosmology. The result certainly marks Jett out from the settler-colonialism of resource extraction and settlement-building that dominates similar games, such as the open-world, procedurally-generated No Man’s Sky (2016, the name itself implying the terra nullius of British colonial logic) or Astroneer (2016). There’s something highly effective about characters who see themselves as cogs in the machines of progress that will guide a culture towards pseudo-religious enlightenment, being represented as doll-like figures who the camera leaves behind as you fly away from base, its focus fixed on the horizon, the teleological goal of a nebulous future.

However, scale is also Jett’s downfall. While in its early parts, the diorama-like world plays beautifully with the themes of humans being dissolved into both the project of history, and the vastness of space itself, as time goes on it also begins to become bogged down in this toy-like world. At first the ecosystems we are introduced to from our distant perspective, all brightly-coloured stems and blotches, seem like a deepening of the alien planet we have arrived at. But they are quickly revealed to be the locks and keys you can expect from any videogame, the toylike spheres you grab from alien plants becoming water balloons and bombs, ready to be ‘punted’ at clockwork insects and creatures. The diorama in front of us starts to suggest not the vastness of the universe, but instead the smallness of a toy box. Jett, in short, becomes a game in the most pejorative sense.

Of course the traditional tasks of videogames, coloured locks and coloured keys, mazes and obstacle courses, gauntlets and gates, bring with them their own expressiveness. In a game like the developer Playdead’s Inside (2016),where themes of control (societal, personal, psychological) are reinforced by a series of puzzles which play with those exact themes, (from controlling drone-like slaves, to imitating them in a factory-line inspection) these conventions of interaction can be leveraged as expressive tools in themselves. But in Jett we are disconnected, blocked, pushed-out by the conventions of interaction. For the first half of the game, for example, the horizon of the planet is dominated by a conical mountain, dreamt of by an ancient prophet. When we finally arrive in this place, the sense of history is palpable, and yet to gain entry we must bomb open a glass wall by carrying a ‘natural’ resin through a tedious obstacle course, where the game’s artifice eclipses any narrative or atmosphere.

In its worst moments Jett submits to being a toy then, a series of patterns to occupy the mind, but little else. Its alien odyssey shrinks in scale and meaning the longer we spend time in it, following the pathways laid out for us by its designers, the smaller it gets. This is not so much a failure as it is just a disappointment – in its strongest moments Jett’s flips of scale find their mark and seem to set us in our tiny place within history and the universe, its world growing impossibly large on the screen. To return to that first image, Jett seems to bring out both its ‘bigness’, its ability to instill in us the terror and wonder of scale, and its ‘smallness’, that miniaturized aesthetic and thematic space that both science fiction and games can so often find it difficult to escape.

Gareth Damian Martin is an award-winning writer, designer and artist. Their first game, In Other Waters was widely praised by critics for its ‘hypnotic art, otherworldly audio and captivating writing’ (Eurogamer). Their games criticism has been published in a wide variety of forms and they are the editor and creator of Heterotopias, an independent zine about games and architecture. Their second game, Citizen Sleeper, is coming in 2022. Find them on Twitter: @jumpovertheage.