In a challenge to the Venice Biennale’s defining principles, the project for the French Pavilion is launched in Martinique

We are in a windswept, cliffside garden that tumbles down to a glossy ultramarine sea. Ultramarin is also another way of saying outre-mer, the French legal term for persons of ‘overseas territories’. “When I hear ultramarin,” says the artist Julien Creuzet, “I think of someone fantastical, superhuman.” We are in Martinique, in the French Antilles, buffeted on one side by the Caribbean Sea, and on the other by the Atlantic Ocean. Creuzet, raised on the island, will represent France at the Venice Biennale 2024 and has chosen to bring the announcement of his project to Martinique instead of Paris; so here we are, a group of press, about to tour the island. The Négritude movement shaped Creuzet; and today we are in the garden of Édouard Glissant’s former house.

In his speech at the launch of Creuzet’s project, the president of the Executive Council of Martinique, Serge Letchimy, promises to install Creole as an official language of the island alongside French. The métropole prefect Jean-Christophe Bouvier is seated across from him; he is the de facto leader of Martinique. Last year he quashed a petition to officialise Creole: ‘The language of the Republic is French,’ Bouvier said to the local assembly (the final decision is still pending). But Creole is as much ‘the language of the Republic’ as French, because ‘the Republic’ itself is entirely constituted by creolisation, the mixing together of peoples and cultures. At least this was the vision that influenced members of the Négritude movement – Glissant, Aimé Césaire and Suzanne Césaire – who supported Martinique’s remaining a territory of France at the moment of its decolonisation. It was, presumably, a way to hold the coloniser accountable, to turn subjects of the colonies into equal French citizens; France had, after all, been constructed by the labour and resources of its colonies. These Caribbean thinkers understood the process of decolonisation not as a quest for the sovereignty of single nation-states, but as the restructuring of the world itself. This was not simply a matter of geography, but of identity, society, language – where the presumed synthesis of nation, culture and citizenship had to be dismantled and reformed.

Creuzet’s insistence on launching his project for the French Pavilion in Martinique, supported by the Institut Français, follows this instinct. He has carefully planned every aspect of our visit, and assembled a cast: his elders, peers and the island itself. Creuzet makes films, sculptures, performances; he also writes poetry. The films are collagelike assemblages of found footage and animation, brought together with music and poetry. His work is at its best when it’s dominated by sound: Creuzet is a composer, a musician; he mixes samples and clips like a producer, with sudden sharp notes, drops in rhythm or longer, more operatic turns. In an early video, from 2015, Oh téléphone, oracle noir (…), Creuzet films himself in a dark room, a phone flashlight pointing at his face, which is held right up to the lens of the camera. He repeats a poem:

Oh téléphone, oracle noir,

toutes les personnes écrans miroirs,

filent les images tactiles,

oh vas-y voir les nuages du soir.

There is a pulpy rasp to his voice, carried with a tilted intonation, and he swells certain words while softening others. Creuzet’s face has an almost devotional capacity: he blinks tenderly, so close to the camera, the scene is raw, and his voice inflected with agony. It’s the title work of a show at Le Magasin in Grenoble, a precursor to the Biennale pavilion (the details of which remain under wraps at the time of writing). A more recent mixed-media installation, Zumbi Zumbi Eterno (2023), also carries this musical tenor – in a video component, Creuzet sings in a whistling voice, and the poem tells a story. Zumbi dos Palmares was a Brazilian quilombola leader, a resistance fighter who famously revolted against Portuguese slave traders. He was decapitated, his head placed on a spike. In Creuzet’s video a twisted body, a cutlass angled into it, is flung into swirling waters. The body turns luminescent, bleeding flowers as fish pass through it. At Le Magasin, in front of the video, a TV screen is propped vertically against a wall, and on it a translucent figure – inside of which, like an X-ray, we see wires, bottles, cigarettes, sweets – who throws, one at a time, a series of books to the front. These last are Creuzet’s library: Ntozake Shange, Sonia Sanchez, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Wole Soyinka, Maryse Condé and of course Césaire, among others. There is poetry and essays; the languages are many.

After the press conference we take a spindly road up to the Absalon waterfall, a sparkling clear spring beloved by artists from the island. It’s a startling green landscape, at the centre of a mahogany forest. Later, octogenarian ceramicist and painter Victor Anicet speaks to us from under his stained-glass mural in Notre-Dame-de-l’Assomption in the volcanic town of Saint-Pierre, where he has tried, he says, to capture the dappling light of Absalon’s tree-dense landscape. Anicet also spells out the present-day Martinican relationship to the land: “We are the guardians of this land, not its owners,” he says, referring to the Indigenous people whose trace has been all but erased from the island, “and they left us an extraordinary land.” The name Martinique (Matinik in Creole) comes from Christopher Columbus’s mishearing of the Indigenous Taíno name for the island, Madiana – island of flowers. In 1635 the French arrived; a year later, a genocide of the Indigenous peoples began. Martinique was turned into a slave colony for the production of sugar, then more valuable than gold. The French imported more slaves to Martinique than were taken to all of present-day us apart from Louisiana (which has a long history as a French and then Spanish territory).

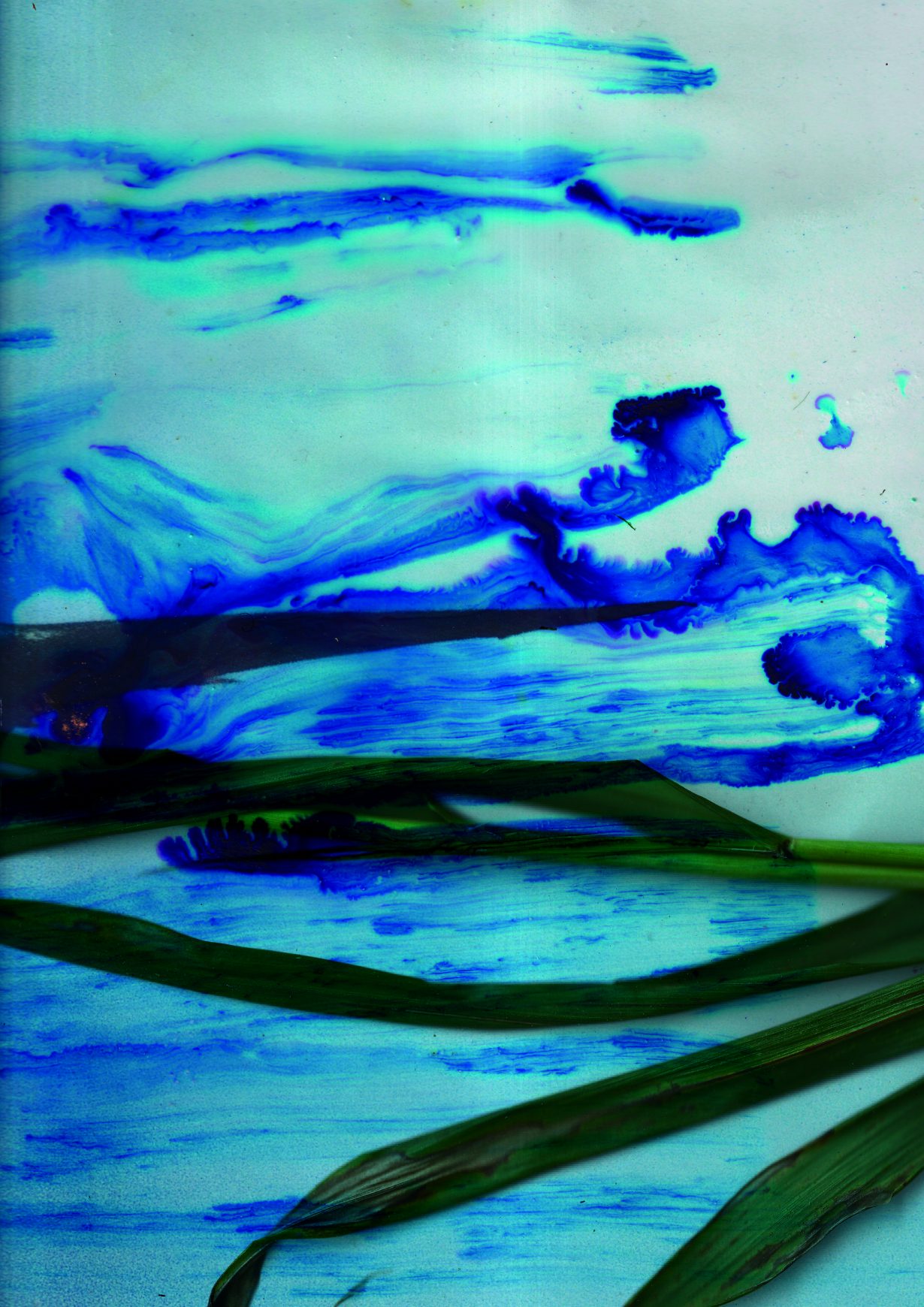

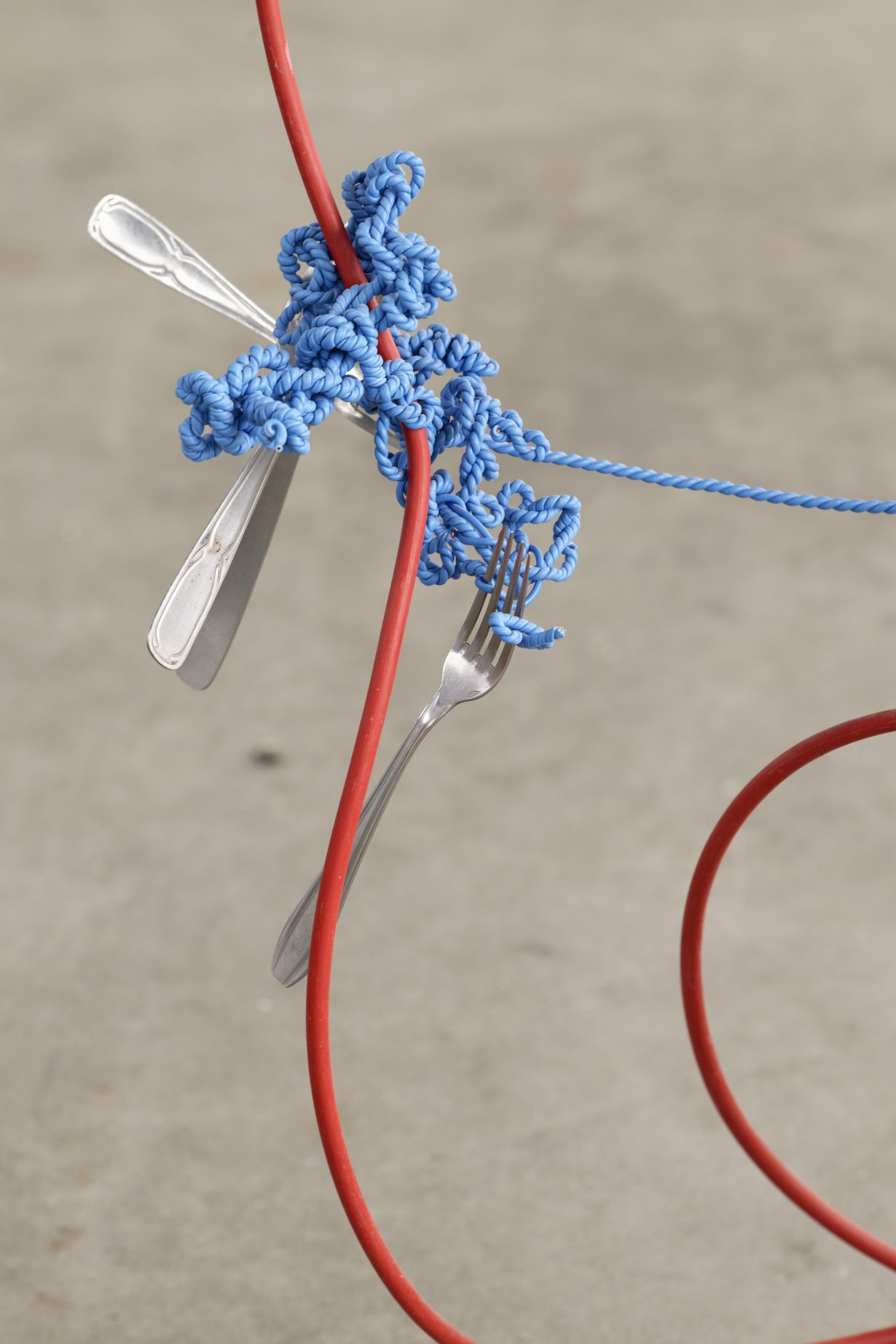

Our trip had begun at the Cape 110 memorial, a field with sea-facing sculptures by artist Laurent Valère. Rough-hewn figures of white stone emerge from the ground; the site, a memorial, functions as a reminder of the illegal slave trade that carried on years after abolition. At the site, Creuzet recited a poem and played a piece of music as we sat, backs to the sea. Glissant wrote that slavery and its Histories – with a capital H – could never be ‘perceptible or comprehensible solely using the methods of objective thought’. Césaire and his classmate the Senegalese president-to-be Senghor both began their adult lives as poets before they turned towards politics. Creuzet in an interview with Platform says: ‘Poetry allows you to put together impossible things’. Césaire’s epic poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to My Native Land, 1939) moves from narrative to high abstraction, as do the closing pages of Frantz Fanon’s Peau noire, masques blancs (Black Skin, White Masks, 1952). The latter forms a part of avant-garde Martinican jazz musician Jacques Coursil’s album Clameurs (2007), which is a sequence of four oratorios with trumpet and voice, where music floats beside recitations of seminal Afro-Caribbean texts. In it, Coursil’s trumpet is almost feather-light, a sound as breathy as a voice. Creuzet’s practice is in complex dialogue with the work of those who came before him: the references are in how he handles poetry and music, and in his use of abstraction. The sculptures that generally accompany Creuzet’s work appear as though swept to the shore from the sea: fraying pieces of cloth and fabric are wrapped around slim structural limbs that are either suspended from the ceiling or emerging from adjoining walls. There are also secrets in this work, not everything is immediately perceptible or translated for the viewer; it’s the right to opacité, as proposed by Glissant.

The second day of our visit begins in the cast-iron-and-glass atrium of the Bibliothèque Schœlcher in Fort-de-France, with a performance by poet Simone Lagrand: “Cette histoire n’a pas de krik. Pa ni yékrak / Cette histoire sera dite même si la cour dort,” she says: This story has no call, no response / It will be told even if the court sleeps. Each word lands hard, like a coin thrown to the floor. Lagrand speaks in Creole, her poem is titled ‘Pays-mêlé’ (2021), mêlé in French meaning mixed; mêlé in Creole meaning chaos, unrest. It is also a verb: to be in trouble, and also to cause trouble. Creole carries a special register of resistance; anticolonial activism has always used the mixing and revising of language to articulate identity and resistance. The Schœlcher was Lagrand’s library when growing up, it’s where she first read Frantz Fanon. It was also Fanon’s library, where he first read the classics of French literature.

As Adam Shatz writes in his new biography, when Fanon was told in school that he owed his freedom to a dead white man he was first stumped, and later enraged. His teacher was referring to Victor Schœlcher, whose book collection the library now houses. In 1802 Napoleon had reinstated slavery (it had been abolished in French colonies in 1794) and its practice was written into the French legal structure; trafficking was sustained even after slavery was abolished again in 1817. In 1848, after a trip through the Americas, Schœlcher petitioned to rewrite the law on slavery in France and its colonies. Victor Hugo describes the scene: ‘When the governor proclaimed the equality of the white race, the mulatto race, and the black race, there were only three men on the platform… a white, the governor; a mulatto, who held the parasol for him; and a Negro, who carried his hat.’ A new era of segregation was inaugurated; white settlers refused integration. In many ways, it persists. There is the Martinique experienced by métropole visitors – the beaches, the wood-cabin shacks full of fried fish – and then that of most Martinicans, who have been priced out by the leisure economy. French jurisdiction over the land restricts the formation of local industries, especially of agriculture, and of any trade between the islands.

One of the few crops cultivated in Martinique is bananas. During the 1970s the French introduced chlordecone, an anti-weevil pesticide, to the island’s plantations. It’s highly toxic, banned by most governments, including in mainland France. Over 90 percent of the population of Martinique (and nearby Guadeloupe) were exposed to the pesticide, which poisoned the soil and freshwater, and islanders have some of the highest rates of prostate cancer in the world. Research shows the two to be linked, and a case was taken to court, which eventually legislated in favour of the French government. We visit the atelier of artist Christian Bertin who grows his own bananas on a piece of land close to the island’s volcano, Pelée, and as the trees ripen, he wraps the fruit in canvas. He then bakes the bound banana fingers in ovens of his own design at a studio comprising at every corner installations made of old metal scrap – gates, fenders, tanks, washing-machine drums. It is a simple, complete gesture, repeated over the years. The baked bananas encased in canvas – large bulbous heads with scraggy limbs – are installed closely together, “forestlike”, he says as he makes us stand under them.

‘La date limite de colonization est arrivé / dlc dlc dlc,’ reads Lagrand’s poem ‘Pays mêlé’ in its final verse. ‘dlc’ is the acronym for la date limite de consommation, the use-by date stamped onto produce. In 2020, the year that statues all over the world ended up in rivers, city bays, the first to fall was here, in Martinique; it was a statue of Schœlcher. We visit the empty plinth, not to survey the stark, blank white platform, but to see what the statue’s removal now more clearly reveals: a mural that has always been behind it. Written by Anicet and rendered in the molten colours of the volcano – red, amber, an obsidian black – it narrates Martinican history: each layer a symbolic reference to the migration, displacement and revolutionary moments that shaped the island. “J’écris un futur différent,” says Lagrand, I’m writing a different future. “Voici un extrait de cette terre / Ne faites pas comme chez vois”, This is an extract from this land / don’t make yourself at home.

Julien Creuzet’s project for the French Pavilion is on view in the Giardini, as part of the 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November

Skye Arundhati Thomas is a writer, editor and curator, currently in residence at the Beaux-Arts de Paris