Karl Lagerfeld has a strong dislike of the analytical process: ‘Analysing kills creativity’, he likes to say. Yet the careful, masklike image that acts as some kind of shield in his endlessly scrutinised life makes him an irresistible subject. Costumed in sunglasses, ponytail and high white collar, Lagerfeld’s day-to-day resembles a grand performance, the fruit of meticulous self-creation and great control. His inscrutability somehow condemns him to face ceaseless questions on the same unchanging subjects: his cat, his diet, the theme of his collections, his hair, his clothes, his opinion of other celebrities, of other designers, the contents of his iPod, of his cat’s iPod and so on and so forth. To the fashion world, he is a reassuringly constant, and apparently endless, source of fascination.

Above the Chanel store in St Moritz, music is pounding and slender women are contemplating delicate rosettes of sashimi. Edward Ruscha, Jr, is on the decks, and the 12cm heels of the glossy, be-Chaneled guests belie the thick February snow of the high Swiss Alps. Two hours late for the vernissage of his own show, Karl Lagerfeld slides quietly into the gallery and is encountered by a bank of camera lenses. He shakes every proffered hand, smiles, poses, chats, poses some more and gives good quote during almost three hours of interviews in as many languages. He is surprisingly funny, engaged and patient.

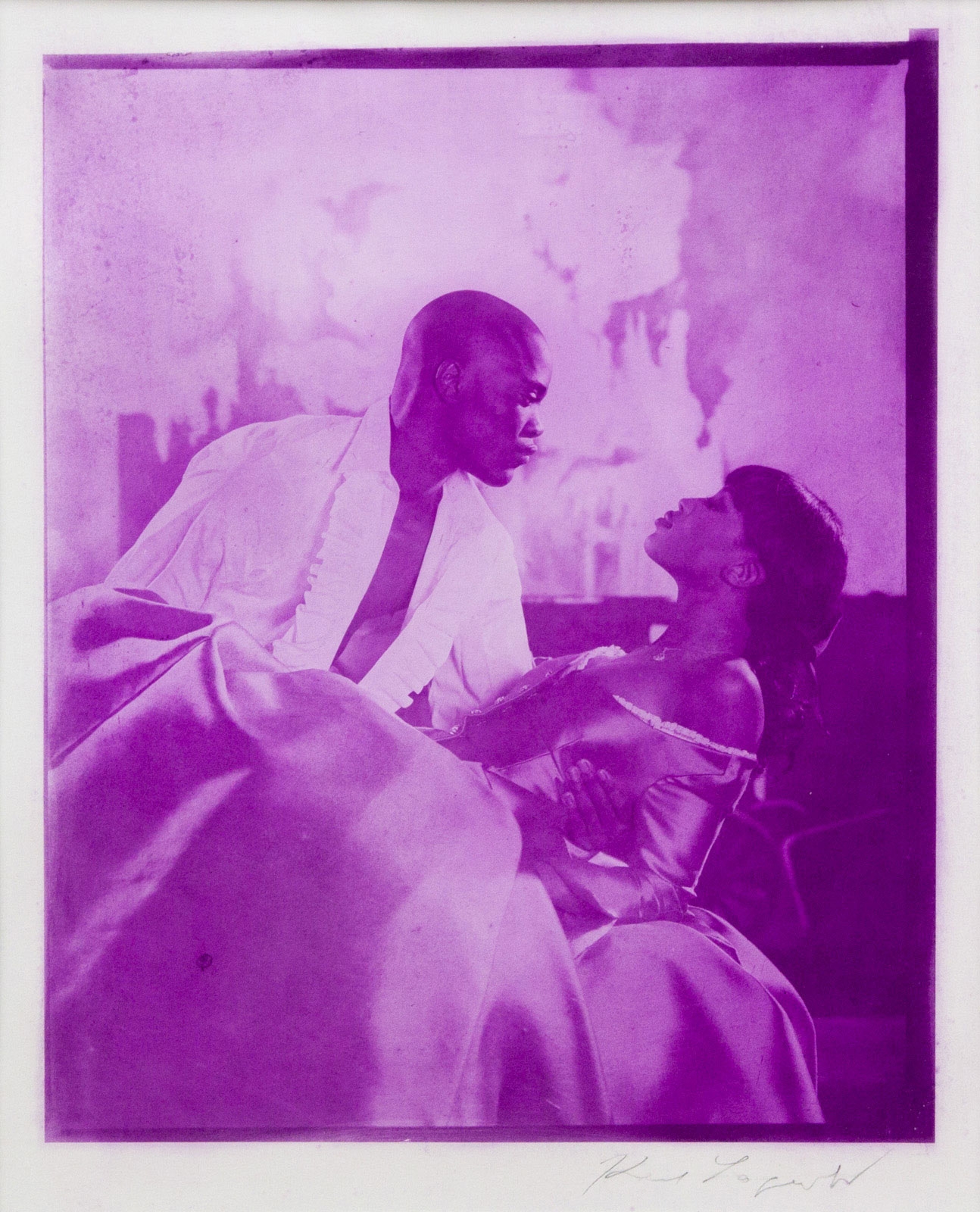

In the middle of all this, somewhat overlooked, are artworks – nine monumental sheets of glass into which ceramic pigments have been fused at a heat of 1,000°C. The images on the glass are based on three portraits that Lagerfeld took for his book The Little Black Jacket (2012). Presented here as triptychs, each image is fused into the glass in progressive degrees of rasterisation, becoming, by the third, fractured and abstract. While the process has noble associations (fire etching and fusion is used for church windows), this application is irreverent in the extreme: the subjects are models and a rap artist, the images have already been published and the colours are intentionally synthetic. Karl has gone Pop, albeit expensively so.

This is the St Moritz outpost of Galerie Gmurzynska, a Zurich-based establishment with a 50-year pedigree and an important grounding in European abstract art (earlier this year the gallery loaned Tate a number of key works by Kurt Schwitters). Gmurzynska has been showing works by Lagerfeld since 1996, not, they admit, without some criticism, particularly in the early years. Endearingly, he first contacted them as a fan: a visitor to their exhibitions and an avid collector of their catalogues. He is passionate about Kandinsky, and did a show with the gallery inspired by the work of Lyonel Feininger. Although he prefers Feininger’s earlier works, the Bauhaus appetite for a dialogue between multiple artforms, fine and applied, resonates with him “100 percent”, in particular the works of Oskar Schlemmer and Walter Gropius.

Lagerfeld’s exhibitions at Gmurzynska are reductively photographic, but that seems a mere excuse for him to experiment with recherché techniques: a rare form of printing using honey and rubber, adapted from a method used by Alphonse Poitevin; giant-format Polaroids; green platinum prints and now fire etching. He explains with some pride that these are the only fire etchings of this size in existence. Naturally, he is interested in the value the complex technique and concomitant rarity of the prints affords. “It’s a little like an haute couture dress,” Lagerfeld admits, though he by no means feels alone in his drive constantly to do things that have not been done before. “It is the dream of everybody in fashion and photography, I suppose.”

Lagerfeld’s encounters with art and other visual stimuli happen as part of the great omnivorous cultural whirlwind that travels around him – ever gorging, never satisfied, yet leaving him, at the centre, somehow touched but unchanged. At one point he compares himself to a building with a television antenna, receiving information that somehow passes through him. “I catch a lot and forget about it,” he says, with a hint of flippancy. Despite the fashion-world addiction to the new and the next thing, not all of his dealings with culture are as disposable as all that. Lagerfeld is surrounded everywhere by books, the result of a mania for print and paper that he says “started the day I could read, and got worse and worse”. He estimates his personal library to now number some 300,000 volumes, most of which are books on art and photography. “I think that it’s very important to be totally informed, to absorb literally everything that is interesting that is going on in the artworld of today and the past,” he says.

“It becomes a kind of treasure in your mind.” Lagerfeld’s late arrival in St Moritz comes as a stop-off after a demanding visit to the Fendi atelier, three days in advance of their show in Milan. His flight back to Paris will take him to Chanel a week before Paris Fashion Week. Somewhere in his peripatetic schedule as creative director of both fashion houses, he must fit in preparations for near-simultaneous product launches under his own label, and the unveiling of a collection he has created for the Brazilian shoe brand Melissa. Books, at this stage in his life, are his primary point of encounter with the artworld; they are fellow travellers for the man who never stops moving. He ingests visual material and art criticism like a kind of brain food, describing the “feeling of richness that art can give you in your mind”. Does it influence his work as a designer? “Certainly,” he says. “But you have to keep it on another level and still listen to your instincts. You don’t know how your instinct was influenced by it – you cannot and you should not ever analyse it, that’s very dangerous.” In the only instances where art has had an identifiable link to his design work – using, for example the colours of Marie Laurencin paintings for Chanel Haute Couture – it has been what he refers to as “mostly not too serious art”.

Discussing his work as a designer, he often cites the importance of instinct and emotional response. While he feeds his mind constantly with printed matter, the people around him, their physical forms and personalities, are of equal importance in his creative process. “Without ‘muses’ the process would be very abstract and lifeless,” he says. “They help with an emotional effect. They prevent cold synthesis. They help to give things expressions and form without knowing it. Our consciousness cannot only be aesthetic. I may prefer to see first through the medium of art – but a ‘muse’ brings it back to life… They enrich the purely aesthetic part of my work.”

A week after St Moritz, in Lagerfeld’s Paris photography studio, waiting again for him to arrive after a fitting (this time Chanel prêt-à-porter), I am tempted to squint and look at the structure of his aesthetic universe and see in it an echo of a master artist’s atelier from the seventeenth century. Books line the vast chamber, three storeys high, accessed by metal ladders. In the print room, the publisher Gerhard Steidl (with whom Lagerfeld has a close working relationship of many years’ standing) is checking vast sheets of handmade paper impressed with thickly textured ink, preparing them for exhibition in Milan in April. Delicious young creatures sit ready to be called upon to pose or strip for the lens. Technicians, riggers, legal advisers, makeup artists, security guards, assistants and assistants to the assistants wait in a full state of preparation for his arrival.

He is not averse to the atelier parallel, although explains that technical complexity ensures that his expansive setup is also part of the modern way of image-making. “I like the idea of the artist’s studio of the seventeenth century,” he agrees. “Van Dyck died at forty-two; he could never have done all he did without his studio, but it is all still ‘his’ work and nobody else’s. Rubens is the same. Both were great sketching artists: Rubens the best of all of them. Today for fashion and photography if you want to do it on a certain scale there has to be a ‘studio’.”

His mention of sketching is significant – before it ever occurred to him that one might make a living through fashion, he wanted to be an artist, specifically an illustrator or portrait artist. The sketch is still his main medium of communication, but also something that he does compulsively and with great joy, explaining that he never goes anywhere without a pencil and block of paper. The sketch is his purest point of connection to the finished items made in his name – he prides himself on the skill of his technical drawings. “In my professional sketches for fashion, I don’t want to be conceited, but I’m pretty good,” he says. “I see in three dimensions and I have a technique that I can put it on paper and the people that I work with can read the sketch as if they see the dress.”

For someone who prefers handwork to anything else (despite his image adorning iPhone cases, he favours writing letters over phone calls), it is extraordinary how heavily mediated is every thread of the output that appears under his name. Later on, during Paris Fashion Week, Twitter is awash with sketches of a shoe he designed for Melissa with a high heel shaped like an ice-cream cone. He is so prolific that his sketches now communicate not just the technicalities of the designs, but the proof that they are his.

In his head there is a clear distinction between his gallery work and fashion work, between his ‘trade’ publications and his art publications, but he can also see evident, felicitous crossover points in his output. His considerable business and design acumen notwithstanding, Lagerfeld admits that he is attracted to the artistic ideal of working without commercial considerations, but at the end of the day he is, at base, a designer: “One should not become too pretentious in that direction. I feel very free and very lucky.”