The architecture of a ‘Gulf house’ hardly ever adheres to a particular style or school of thought, but for those even vaguely familiar with the social history of the migrant Malayali, these houses are easy to tell apart from the rest of Kerala’s building styles.

According to the 2018 Kerala Migration Survey (KMS), conducted by the Centre for Development Studies, 2.1 million people from Kerala were working abroad that year, employed in a range of blue-collar and professional capacities. Of these, an overwhelming majority, 89 percent, or 1.89 million, lived in the Gulf peninsular region – the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The survey estimated that one in four Indians in the Gulf was from Kerala. This Malayalam-speaking population from India’s southernmost state are colloquially referred to as Gulf Malayalis. While the migrants are spread across religions, over 40 percent are Muslims, according to kKMS, including the Mappila community from Kerala’s northern Malabar region.

Houses built with Gulf money tend to be huge, bigger than most middle-class homes in India. They liberally borrow elements from art deco, Palladian and other identifiable architectural styles, as well as aesthetics picked up from social media, the houses of celebrities photographed for local magazines or the homes of arbabs – masters/bosses – in the Gulf.

A lot of these palatial bungalows are also vacant for up to ten months each year. According to the 2011 census figures, the latest numbers available, about 11 percent of houses in Kerala, roughly 1.19 million, lie empty. This is a lot higher than the national average of 7.45 percent.

What and who are these houses for if they are only lived in for two to three months a year? Does the house, inanimate as it is, feel a sense of abandonment? Why does one build a house that may never really become a home? These are among the questions Juneida Abdul Jabber, Shahnaz Hashim and Zahra Mansoor, an artist, an architect and a researcher respectively, based between Dubai and Kerala, have been seeking to answer via their research project Another Empty House (2020–). All three belong to the Mappila community, and the focus of their research has, so far, been on case studies and examples from within this section of the migrant population.

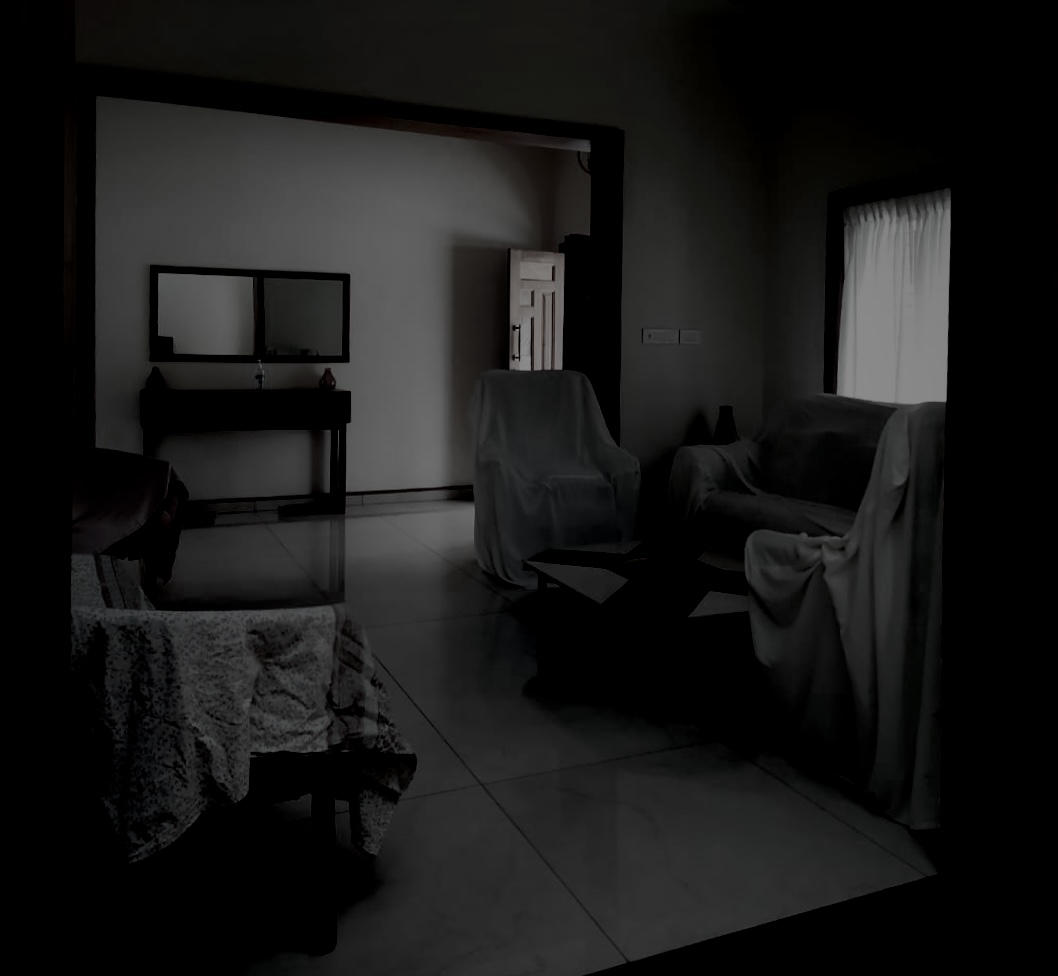

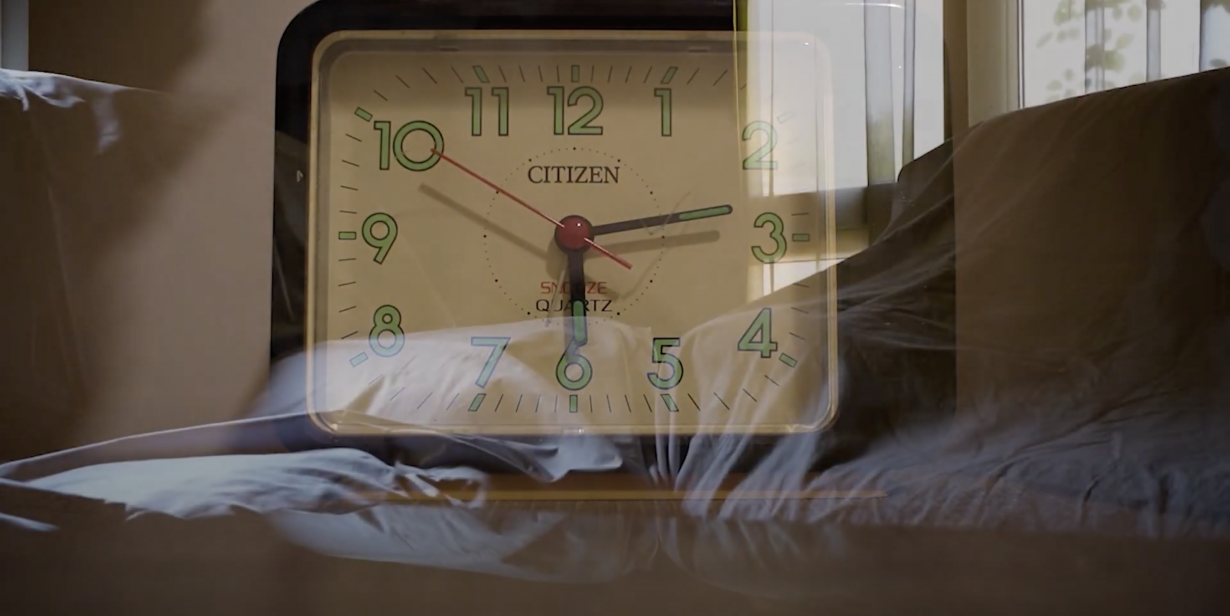

Their first production, an experimental video collage called Weight of Emptiness (2021), treats these empty houses as feeling entities that experience loneliness and neglect for the greater part of the year, except for the brief months in summer and winter when they are filled with people returning ‘home’ on vacation, for weddings or festivities. The three-minute video, recently screened as part of an online show for Rumman Collective – artists and researchers who promote dialogue and collaboration between early-career artists – represents a whole year, every 15 seconds standing for one month. Shots show a dead cockroach, a clock whose fading battery struggles to power the second hand, white sheets covering furniture, while rubbings made against crumbling walls are overlaid on the images.

As the summer months approach, the pace picks up, suitcases are wheeled in, the family returns. There is a wedding, the laundry basket is full, as is the wardrobe. There are several pairs of footwear by the front door. The kitchen is busy, as is the dining table, where people gather. Then sheets are returned to the sofa and chairs, carpets are rolled up and covered, and the pace slows again too. The house goes back to emptiness, dust and neglect; it’s a cycle we can presume repeats year upon year. Throughout the video, a contemporary Malayalam poem by Iqbal Shamz is layered onto the images, while a soundtrack of desolation plays in the background. The words in the poem do not evoke nostalgia for the homeland, but speak matter-of-factly about the necessity of migration, of the pressure to save money to build a house and marry off daughters lavishly – the two chief objectives that drive most people in the Mappila community to work abroad – and the social cost of making such choices.

The decades-old phenomenon of Malayalis in the Gulf – the peak was during the 1970s oil boom – is but a continuation of an economic relationship stretching back to the fourth century BCE, when first Arab, then later Roman and Greek traders used monsoon winds to sail to the Kerala coast for trade. The demand for spices, especially ‘black gold’, or pepper – so expensive that Europeans paid for it with gold – also brought Islam to Indian shores via the early Arab middlemen. Centuries later, Muslims, who form the bulk of the Gulf Malayalis, would find that the influence of these old historical, social and religious ties made it easier to migrate to Arabia instead of further west.

Today, the demographics of Malayali migrants are far more diverse, including women and professionals like doctors and engineers who can afford to take their families with them. For them, as too for those who are forced to leave families behind, the building of a house – not merely buying one, Jabber, Hashim and Mansoor point out – is the foremost measure of success.

Jabber, Hashim and Mansoor note that the idea is hardly to create a home: the size of the building directly reflects pride and aspiration, and functions as a status symbol and display of wealth when it comes to fixing arranged marriages for children. Every effort goes towards making the building as grand as decades of savings allow. Owning an apartment does not allow for the same bragging rights. Such is the frenzy that surrounds Gulf money and the economy it funds in Kerala, the three note in their research, that billboards advertising gold jewellery and construction materials – cement, iron rods – are abundant throughout the state.

Within the Mappila community that observes the purdah system, there is also a trend to build houses big enough to contain two kitchens, two living rooms and so on. Where one set of rooms are performative, male spaces, decorated elaborately to display the family’s wealth, the second set is simpler, restricted to women, perhaps more ‘homely’. Apart from requiring greater resources and space, these houses also drastically change the regions in which they are built by driving up real estate prices and living expenses. Those who never migrated are left to bear

the brunt of this inflation. Much is said about the influence Gulf Malayalis have on Kerala’s economy and politics. The Kerala Migration Survey estimated that remittances from this community in 2018 totalled about 850 million rupees, a large chunk of the state’s economy. Several migrants who have climbed up the social food-chain also enter politics, fund influential cultural events like the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and contribute to infrastructure projects in their villages. But not as much is said about the social impact on both those who leave and those who remain. The ‘Gulf return’, a ubiquitous term for those who come back to India because they have to – the Arab states don’t grant migrants citizenship, and their children cannot assume hyphenated identities – are barely able to hold on to their place within their families, let alone the community. They have been away so long that when they return, many don’t have relationships with children they have not seen grow up; conflict arises with wives and daughters resentful of giving up control over the household finances they managed for decades in the absence of men; there is little of the old community these migrants left behind.

Having built up over the last half century or so, tensions caused by migrant Malayalis working in the Gulf are complex and far-reaching in how they have shaped Kerala. Another Empty House, even if in its infancy, sheds a sobering light on metrics of luxury and success that says more about a particular social landscape than about any individual achievement.

From the Winter 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia