From portraits without pictures to predatory prey, the South Korean artist’s idionsyncratic work delights in upending established orders and power dynamics

It is a vanishingly rare event, but it does happen: an artist makes a work that is so effective, so potently charismatic – too charismatic, you could even say – that it takes on a life of its own. This is a fraught experience, at once a gift and a curse. The piece may win its creator new fans, but as it circulates, various odd, and sometimes ill-informed, interpretations have been known to accrue.

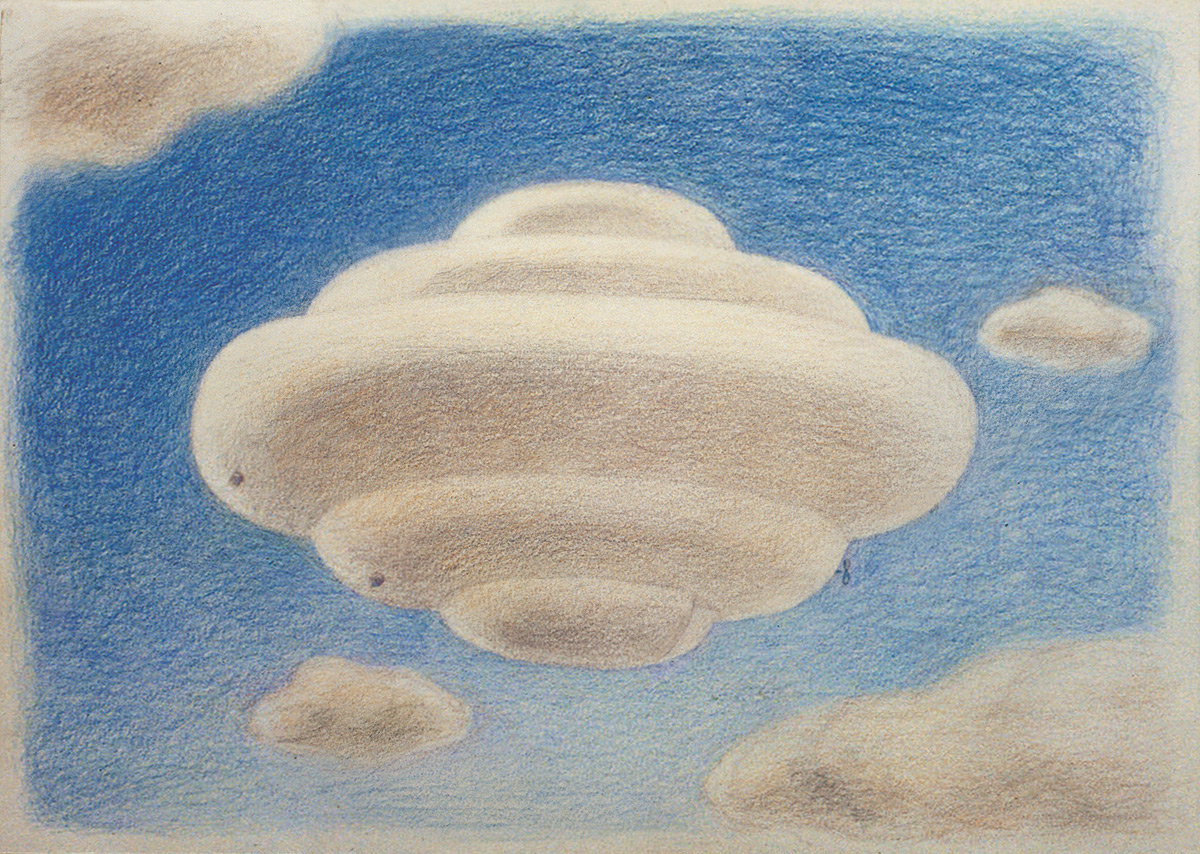

The South Korean artist Kim Beom, who is fifty-nine, has made such an artwork: a spellbinding 2012 video titled Yellow Scream, in which an actor, Choi Kyong-Ho, demonstrates how to make an abstract painting in 30 minutes. Staring straight at the camera, the man counsels his viewers: “You may find it hard to think about something or make decisions” when painting. His advice: “Don’t think; just choose your colours and move your brush as you feel.” And so he proceeds to do just that. As he makes careful horizontal strokes in shades of yellow, he leans towards the canvas and screams. This artist has range. He paints what he terms “some screams of unbearable confusion” and “a short scream expressing a flashing pain”. Each mark, each scream, is a bit different.

A quick internet search can yield stories about it on clickbait-y sites with headlines like ‘Try Not to Laugh as This Man Calmly Paints Yellow Lines While Screaming’ and ‘Meet the Anti-Bob Ross of Korea’. That latter characterisation seems particularly misjudged – the actor actually comes across as decidedly pro-Ross, exuding the same earnestness and equanimity as the beloved TV painting-instructor. He is sincere and patient, and he wants you to learn. The issue is just that this painter’s artistic goals (and Kim’s) are a bit more antic than Ross’s.

Kim may not be satirising Ross, but he has other targets. Yellow Scream comes across as a sendup of both a certain type of rarefied abstraction and the outrageous claims that are made about its ability to transmit emotions, narratives and ideas. It recalls Tom Wolfe’s indictment in 1975, in his book The Painted Word, that art was no longer about ‘“seeing is believing,” you ninny, but “believing is seeing” for Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text’. (The emphasis is Wolfe’s.)

That is not to say that Kim is some archconservative, lobbying for a return to theory-free visual pleasure. He is no anti-intellectual. A piquant scepticism and a zest for invention (frequently camouflaged as nonchalance) define his idiosyncratic practice. Across various mediums, in diverse tones, his artworks prod viewers to consider what they are willing to believe, and what they are willing to accept – aesthetically and politically.

A 2010 installation, Objects Being Taught They Are Nothing But Tools, enacts an indoctrination session. It places cheap household products – a table fan, a kettle, a nightlight – in tiny chairs in front of a chalkboard and a television, on which a man delivers a tedious lecture. “Some of you use electricity,” he says. “Others use batteries.” You may find yourself feeling sorry for them. Reminding myself that they were only objects, I just felt sorry generally, thinking of all the systems of control we construct and endure.

Kim delights in highlighting and upending power dynamics with light touches and deadpan humour. In a 2010 video, Spectacle, he reverses the action of nature documentaries and has a cheetah fleeing a superfast antelope. In other video installations from that year, we encounter A Ship That Was Taught There Is No Sea and A Rock That Was Taught It Was a Bird. A 2008 canvas called Denial presents a kind of challenge to its viewers, plainly stating in black letters, ‘THIS IS NEITHER A CANVAS NOR A PAINTING’ and ‘THERE IS NO SUCH THING HERE’. As the old saying goes: who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?

All works of art ask us to suspend our disbelief – or, at least, to believe in them. (‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’, another trickster, René Magritte, informed his viewers.) Kim makes this moment of decision, this choice, the fulcrum of his art. He ‘emphasizes the internalized action of the viewer to believe or not believe’, as the curator Paola Morsiani has written about Kim’s (sometimes-sinister) pedagogical installations. In 1994 Kim used a pencil to draw a small circle on a piece of paper and wrote, ‘believe this circle is alive’, ‘believe this circle can think’ and a couple other bold imperatives. Are you buying it?

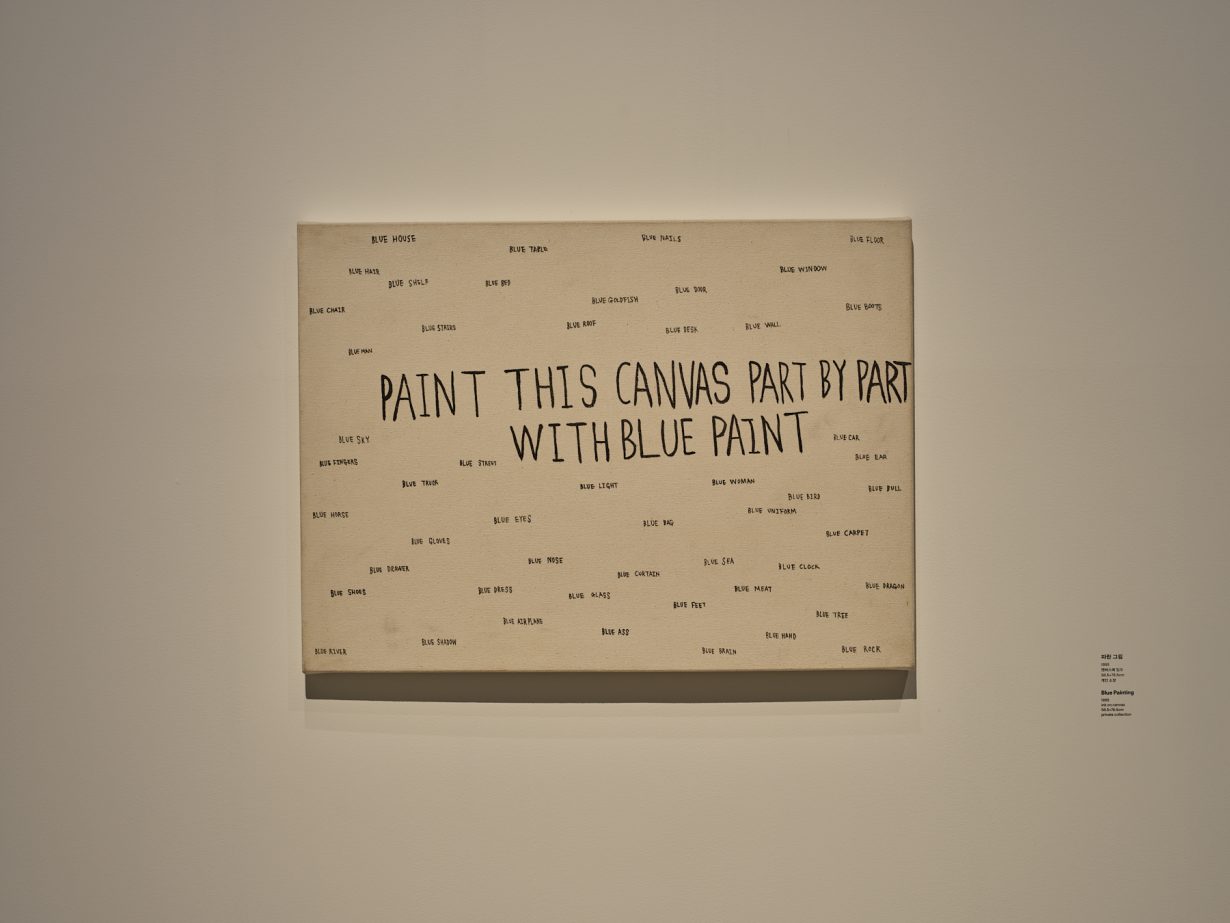

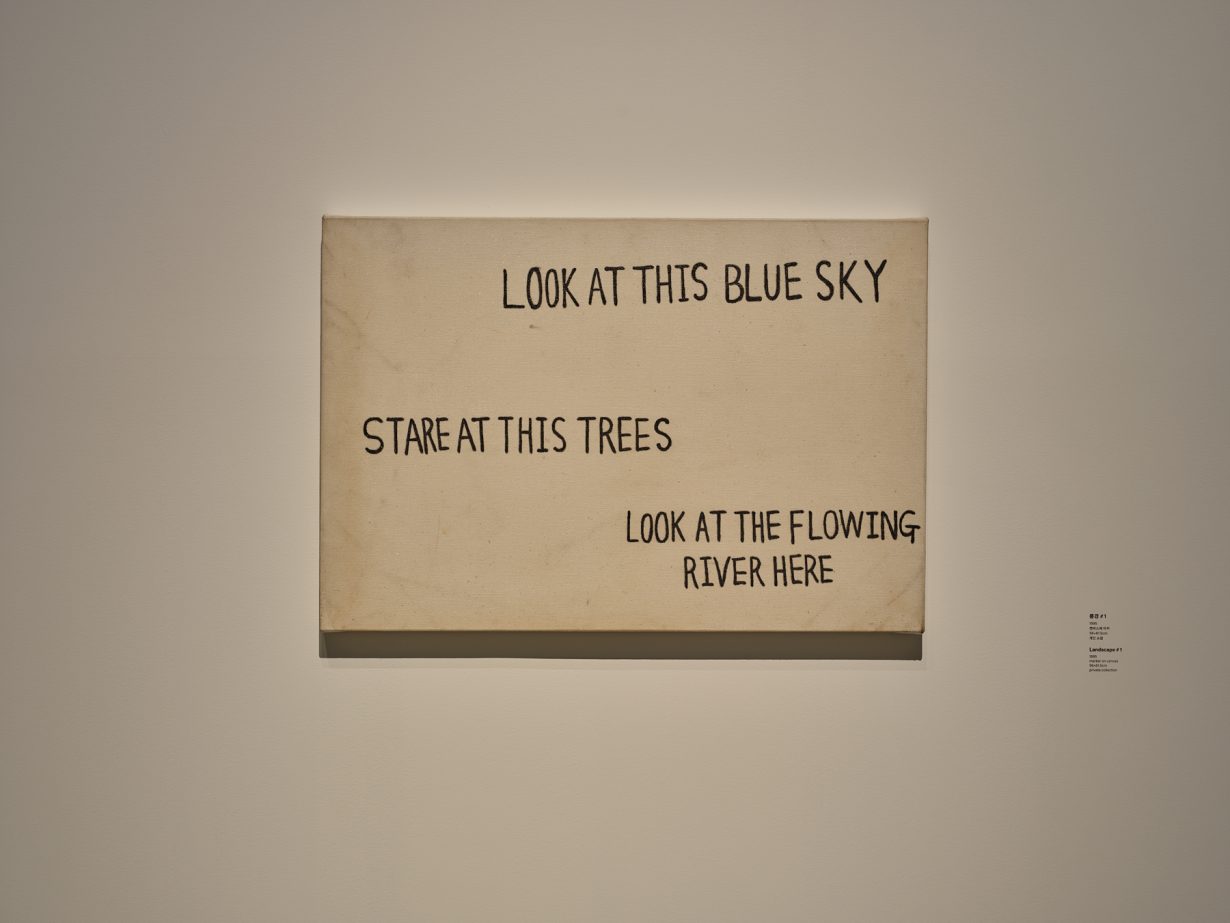

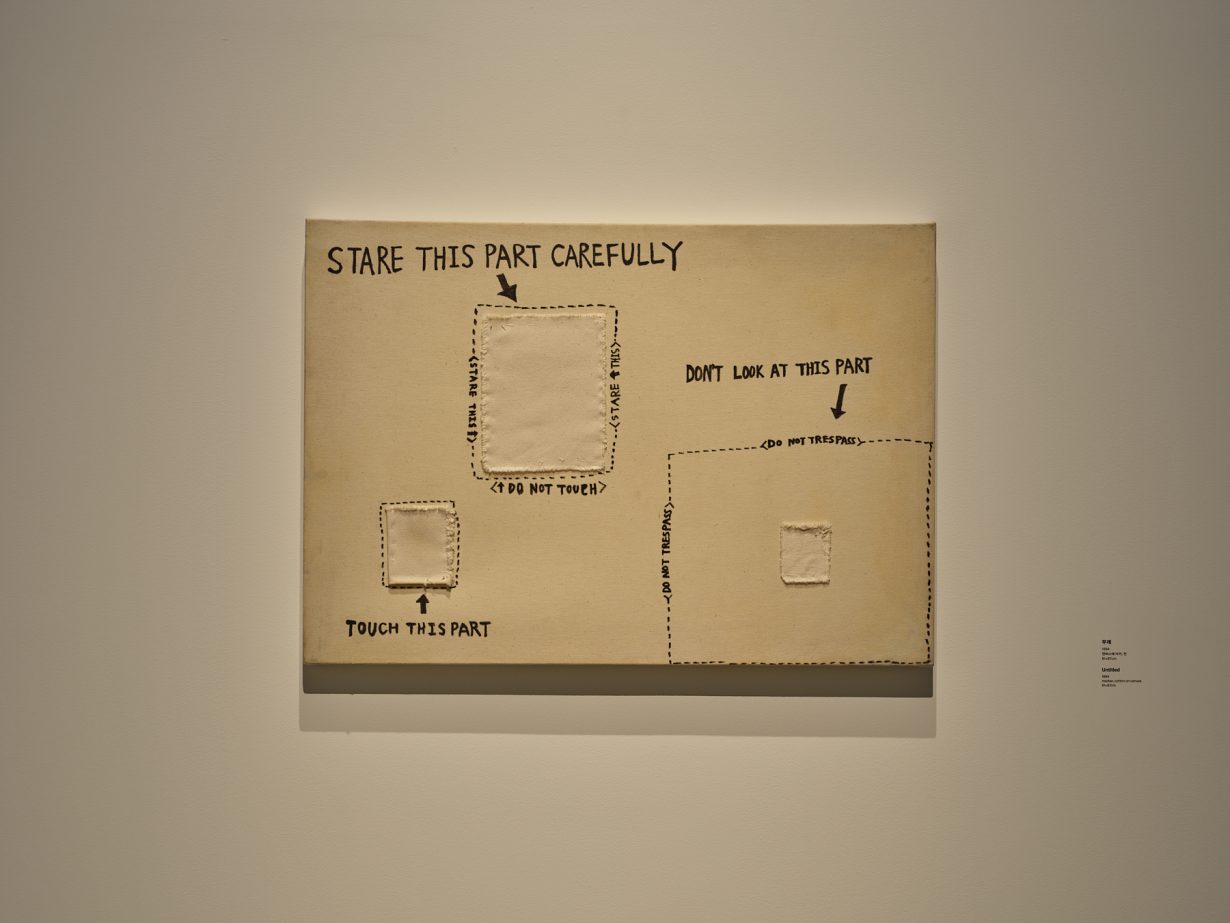

Kim started out as a painter, and in his formative works from the 1990s you can see him questioning artistic customs, toying with how a painting should behave, how it should look and how it should address its audience. He cut into a canvas, folding the flaps and attaching buttons to make shirt pockets for Self-Portrait (1994). He sewed together rectangular slices of canvas to render Brick Wall #1 (1994). And he affixed cotton swatches to a canvas and used a black marker to draw arrows and lay down some rules: ‘DON’T LOOK AT THIS PART’ (too late) or ‘TOUCH THIS PART’. An untitled 1995 piece bears a rolled-up paper and a note: ‘TAKE THIS POEM WITH YOU’. At Kim’s current retrospective at the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, a gallery attendant at the entrance informs visitors that touching the works is, in fact, verboten, which makes his pictures both funnier and sad – cut off, alienated.

That exhibition is titled How to become a rock, which comes from writing by Kim that, I think, hints at the abiding conflict within his art, the productive friction that fuels it. In that text, which was part of his 1997 book The Art of Transformation, he advises: ‘Ignore the changes of the seasons and the weather, and do not think at all’. And he says, ‘Even if it happens that a physical force such as a heavy rain will shake you and roll you down, do not be concerned about it. Just keep your original posture.’ Being a rock apparently involves sticking to your beliefs, but it also means a kind of inflexibility, a wilful hermeticism.

Is Kim a rock? In some sense. He has eschewed a signature style but charted a singular course, wielded the language of sundry art movements for his own incisive ends: the canonical text-based conceptualism of Robert Barry and Yoko Ono, the research-based installation art of so many biennials past, and more. From one vantage point, he is a kind of court jester of contemporary art, poking at its pretensions, stripping it down to its basics and turning it into something else (a painting as a shirt, an instructional video as a comedy act). In a pivotal early effort, he made a painting of chicken and sold it for $11.95, the price of a chicken dish he wanted to buy – a painting as actual currency, pure use value. At the 2012 Gwangju Biennale, he sold paper-clay sculptures of whole chickens and used the profits to buy 2,840 vouchers for underprivileged children to buy chicken. (These are only a few of his chicken-related pieces.)

Taken together, these disparate actions suggest an artist who is endlessly inquisitive about art’s efficacy. Kim has serious doubts about the art enterprise, but he is not a cynic, and he is sceptical only because he seems to want more from art than our present world provides. He is also restless. Each new series he starts leaps across the aesthetic map. One problem of writing about his art is that it has taken so many forms that it is impossible to summarise it all. (Another problem is that many of his artworks are very funny, and it is horrible to explain a joke.)

This is a plainspoken art, and an art that is aware of the cruelties of the world: where lies are told, where people are repressed and where a ship might be taught that there is no sea. Since 2002, Kim has been creating renderings for fantastical, occasionally menacing buildings, like A Draft of a Safe House for a Tyrant (Perspective) (2009), and in 2008 he began a series called Intimate Suffering, which offers dense mazes on canvas, each a hard-edge, Op-art abstraction as an exhausting game. One from 2014 is nearly five metres tall, and while I have tried to complete it, gliding my eyes along its passages, I always give up way before the end. Kim rarely consents to interviews, but he has said of those puzzles, ‘Life comes with its share of problems, and solving problems and finding the right way is hard, but it seems to be human instinct and nature to do so.’

And so we might ask: amid tough times, is it worth trying to ‘keep your original posture’, like a rock? Sure, that has value in a world that demands conformity. But it is at least as important to keep trying new things. Like Kim’s puzzles, with their long alleys and distressing dead ends, one message of Kim’s whole practice is that the essential thing is to keep looking for solutions, to keep going.

Kim Beom’s solo exhibition How to become a rock is on view at Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, through 3 December