The artist on how her painting and worldview is rooted in the natural world

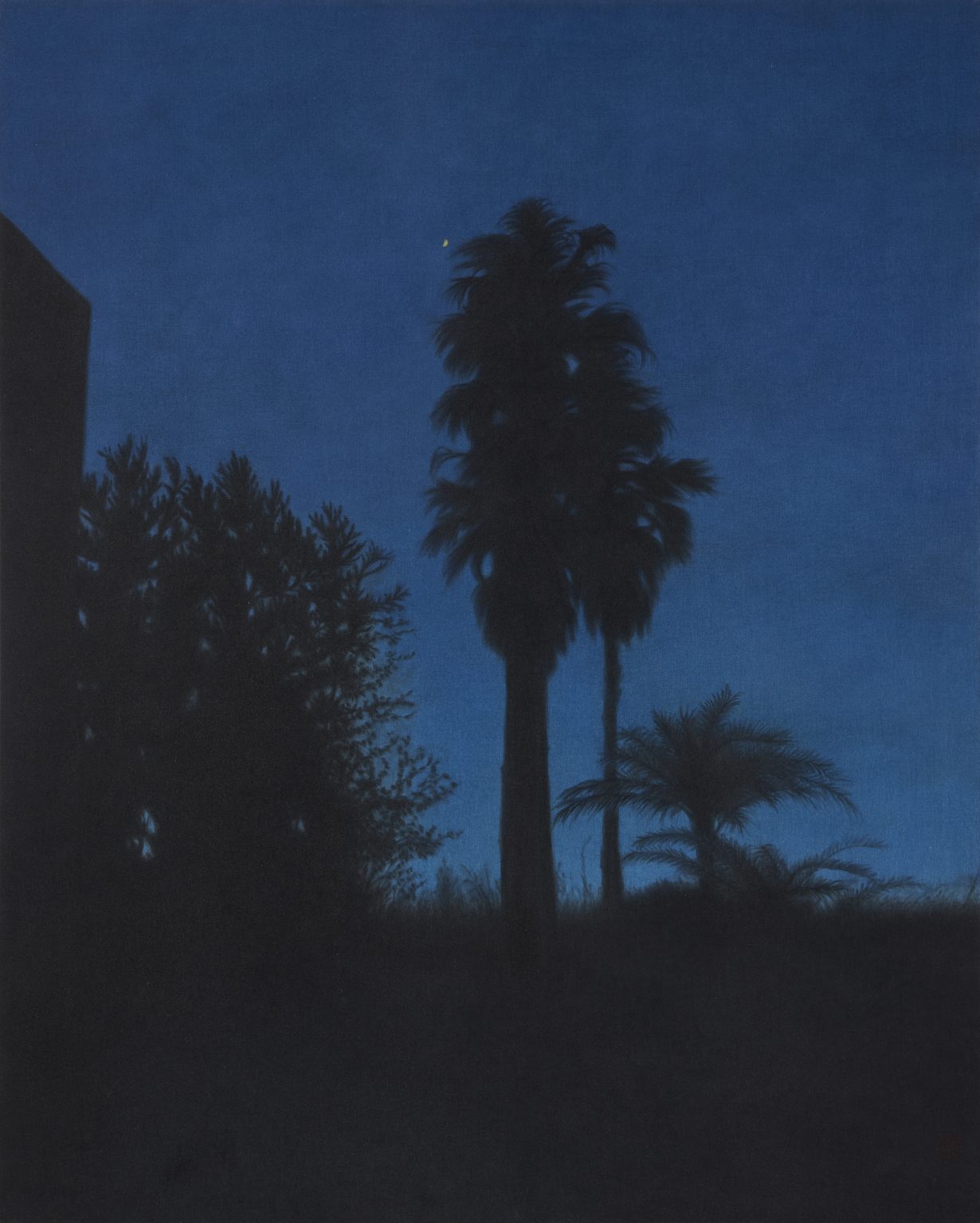

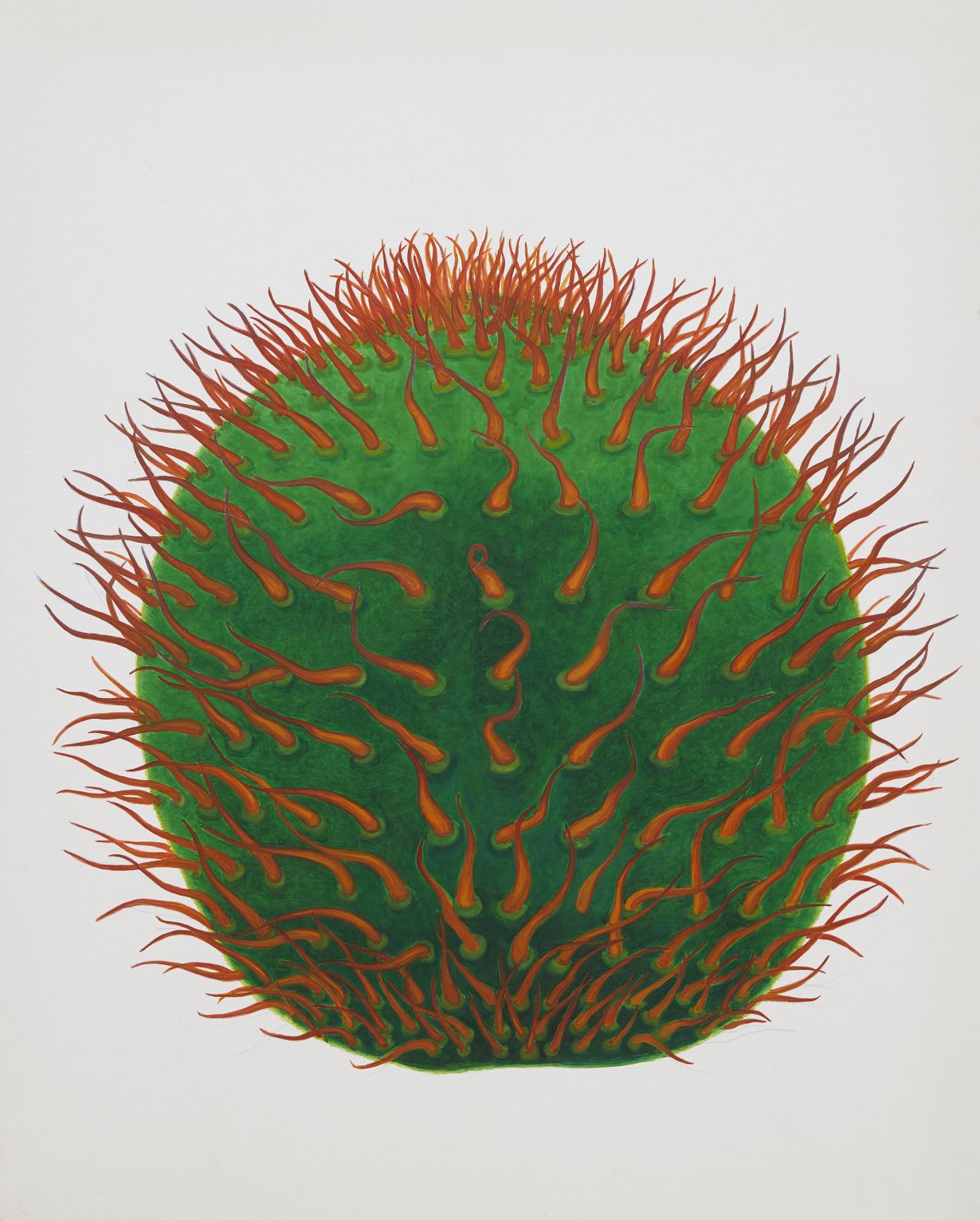

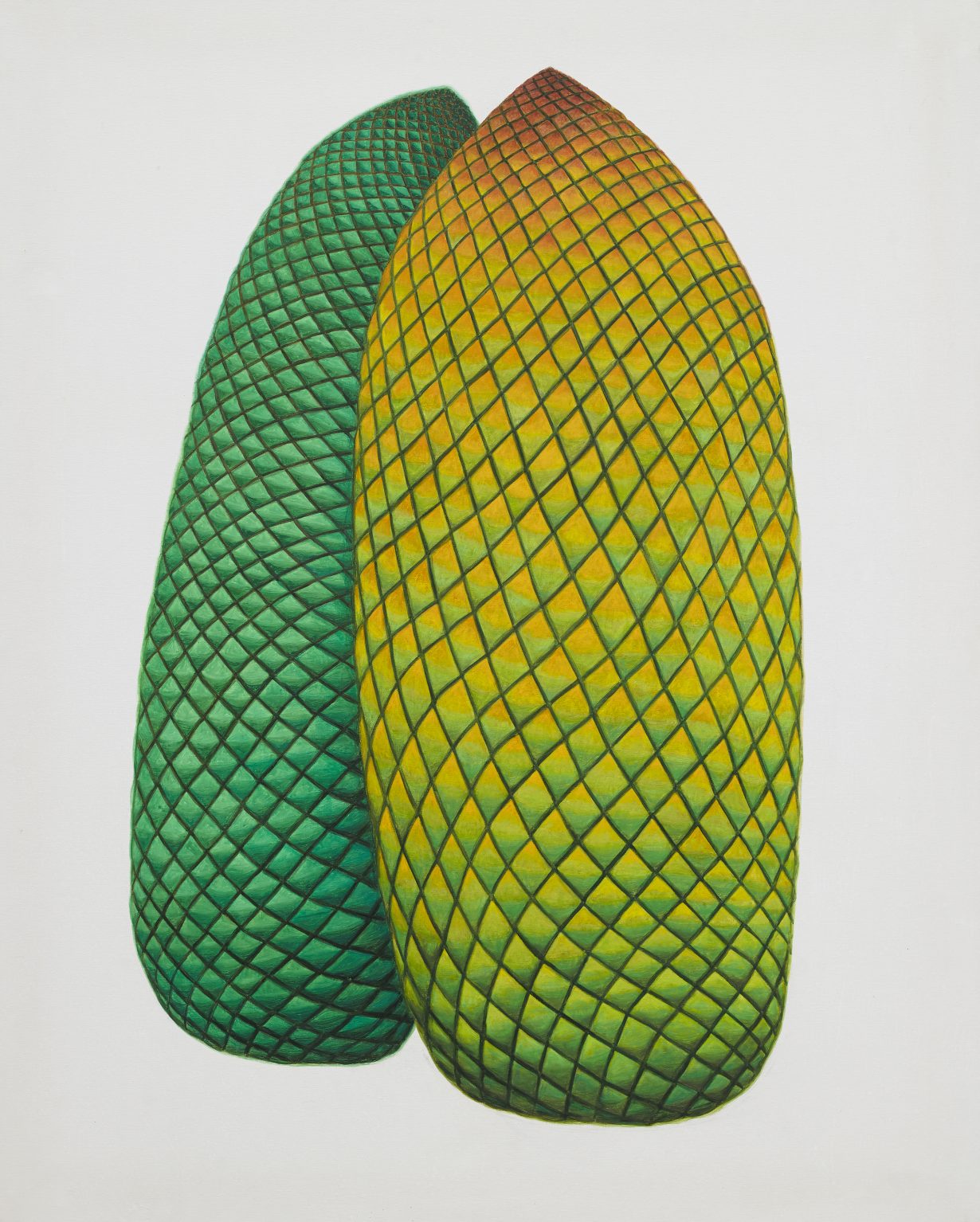

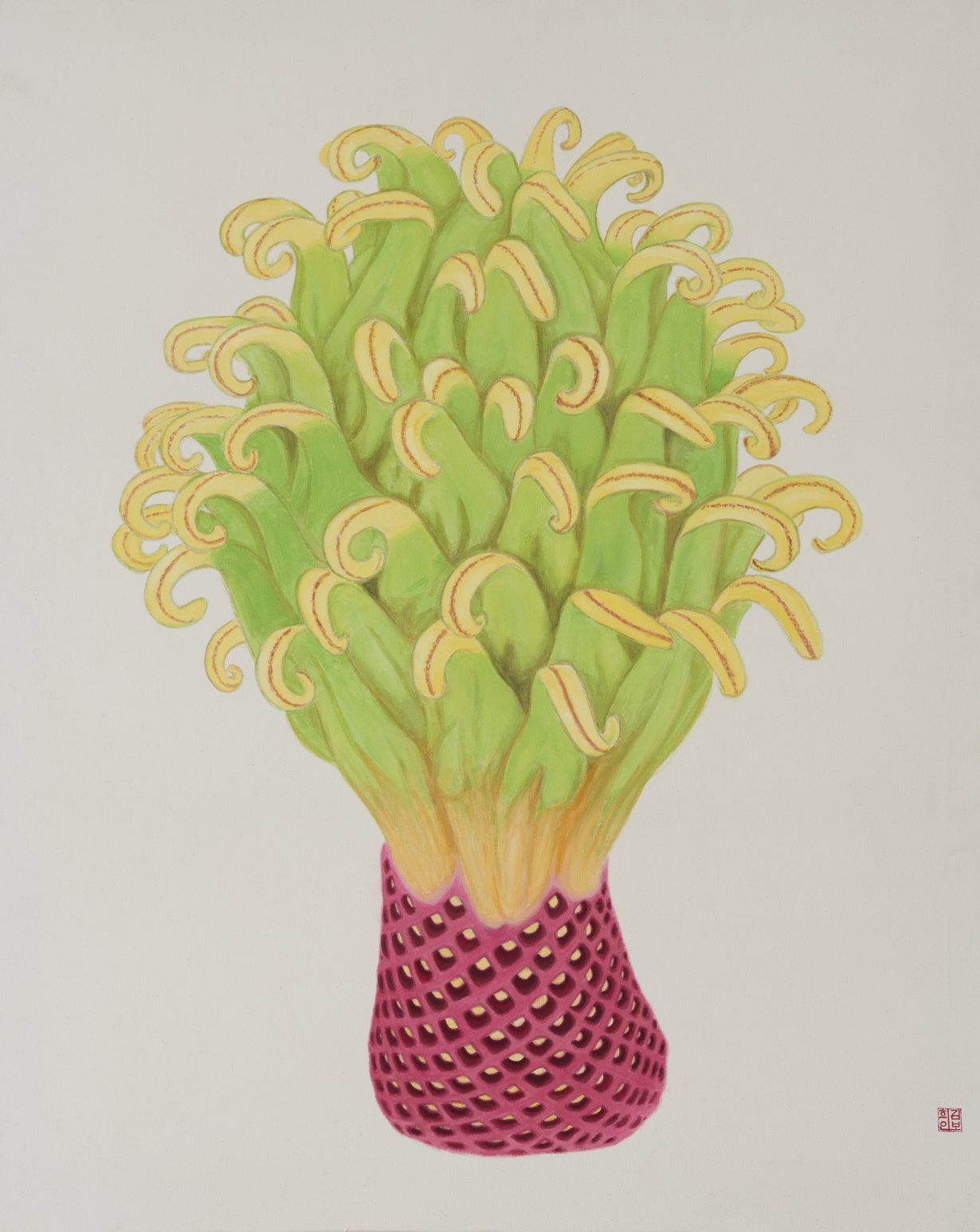

In some ways it’s true to say that Kim Bohie’s work, as it has evolved over the past four decades, emerges from a curious fusion of techniques derived from both Korean and Western traditions. Traditional Korean paper, canvas; inks, acrylics. Aspects of Buddhism and animism; aspects of Christianity. Her representations of plant life (often of the tropical variety) and seascape oscillate between flatness and three-dimensionality, between the blurred and the precise, between near monotones and fabulous displays of colour. Between the indexical – such as in the Jungmoon series, capturing particular street scenes at dusk – and the individual, as in the focus of her Towards series of plant studies from the late 2000s onwards. Throughout, she manages to focus on nature and landscape as both a real, existing thing and an imaginary, a thought or a feeling, without sacrificing the one on the altar of the other. Consistent in her work is an exploration of nature as both a whole and a series of parts: an interconnected structure dependent on light, colour, and a variety of beings. While the human being has appeared less and less in her work, the sense of seeking connection still remains. A series of untitled paintings executed on traditional Korean paper and dating from the early 2000s onwards are almost purely abstract colour studies, albeit with definite horizons, that reinforce a sense of looking, searching, or just paying attention to all that is around us. Such a theme extends that of early figurative works such as Graduation (1981) and Immersion (1984), in which solitary female figures sit with blank or bored expressions, as if they are trying to figure out what, exactly, is going on – something that most of us are trying to figure out these days. The message Kim’s work seems to suggest: look outside yourself.

ArtReview Your paintings tend to depict verdant landscapes and lush scenes of vegetation. What subjects attract you and why?

Kim Bohie I have always been interested in my surroundings, and I always am full of adoration for every scene of nature I find around me. I moved to Jeju Island over 20 years ago, and so the subject of my painting has become rooted in the natural landscapes of Jeju Island, its flowers and palm trees, the sea around my house and Leo, my beloved black Labrador Retriever. My garden, especially, has become an alternative version of my own world, planting Washingtonia palms, Canary Island date palms, agave, hydrangea, rosemary and cactus, and my daily life within them becomes my paintings. The daily scenery that might be unnoticeable to others, things that other people may just pass by rather than an idealised perfect beauty of nature, is more magnetic to me.

AR What is it about nature and landscape that attracts you? Do you find yourself favouring particular seasons?

KB Jeju is beautiful in all four seasons; each has its own beauty. It is hard to feel the change of the season in the city, but here you can feel the energy of the season to the fullest. The reason I moved to Jeju Island is that, unlike other regions in Korea, the fresh green energy still remains in winter due to the warm, sub-tropical weather. I do love all four seasons, but winter scenery appears rarely in my paintings. I adore the summer the most as it brings great bursts and vibrancy of leaves in full greens.

AR What motivated you to become an artist?

KB I liked drawing since I was very little, and my parents were very supportive and let me learn with good teachers. I studied Korean-style painting at Ewha Womans University in Korea, where I learned more about the spirit of artists, about the way artists think, along with how to hold a brush, draw a line, and draw an orchid in the style of Korean painting. At that time, the professors did not like colour painting and nude painting was not welcomed, but I didn’t mind and freely made those as I wanted. My work gradually developed as a combination of techniques. I worked with ink-wash paintings in the past, but this has very unique characteristics as a certain genre of painting. I think the medium has the advantage of allowing the viewer into an imaginary world more freely, because the inner world is expressed only with ink. Writing about my past works making use of ink wash painting, Korean art critic Oh Kwangsoo referred to it as a ‘landscape of meditation’.

Gradually, I began to use fabric instead of hanji (Korean mulberry paper) for my paintings, as I started to work on a larger scale. The pigment paint of Korean painting is not easily absorbed into fabric, so it has to be applied multiple times to become vivid; as a result, I began also using more Western painting materials, such as acrylic, in a limited way. I tend to work openly, making use of traditional materials and influenced by Korean aesthetics, while also drawing on my experience of a diverse array of international fine arts, crossing two boundaries depending on what I want to express and pursue.

AR Given this combination of techniques and influences, where do you draw creative inspiration from?

KB I tend to listen to lots of various music when I work: Johann Sebastian Bach, Korean gayageum instrumentalist Hwang Byung-ki, in a wide range from pop music to classical music. I have always been interested in the field of architecture because I wanted to be an architect when I was little; I still especially love Luis Barragán’s unique use of colour and formal beauty, and the sculptural architecture unique to Zaha Hadid. Aside from the influence of the modern environmental movement, Rachel Carson’s writing is a recurring inspiration, in the way she deeply feels the beauty of the earth and takes a careful look at the wonder of nature. Psalm 8 of the Bible could be said to be an inspiration to me as well.

AR Some of your work is more abstract, some more representational; how do feel these two aspects of your work come together?

KB There are some objects that need to be expressed in a more realistic aspect, and sometimes it is necessary to express a more abstract portrayal. Ultimately, what I’m talking about is the same. Among my works, the paintings of the sea can look like abstractions. I believe that nature does not only have figurative features; nature itself holds abstraction, and I only express it as it is. Rather than thinking dichotomously, I want to express both the abstract and realistic characteristics of nature.

AR Your early work included people; why are there by and large no people in your more recent landscapes? Why did you shift away from the human form?

KB In my early phases, I often drew portraits of people based on my thoughts that humans were the centre of the world. But as I get older, I believe we are just a very small part of nature, and that we have no choice but to coexist with nature. So I began to draw mainly nature and landscapes, where humans were not directly expressed in the work, more in a metaphorical way through the depiction of trees, animals and rocks.

AR How else has your work changed as you have matured?

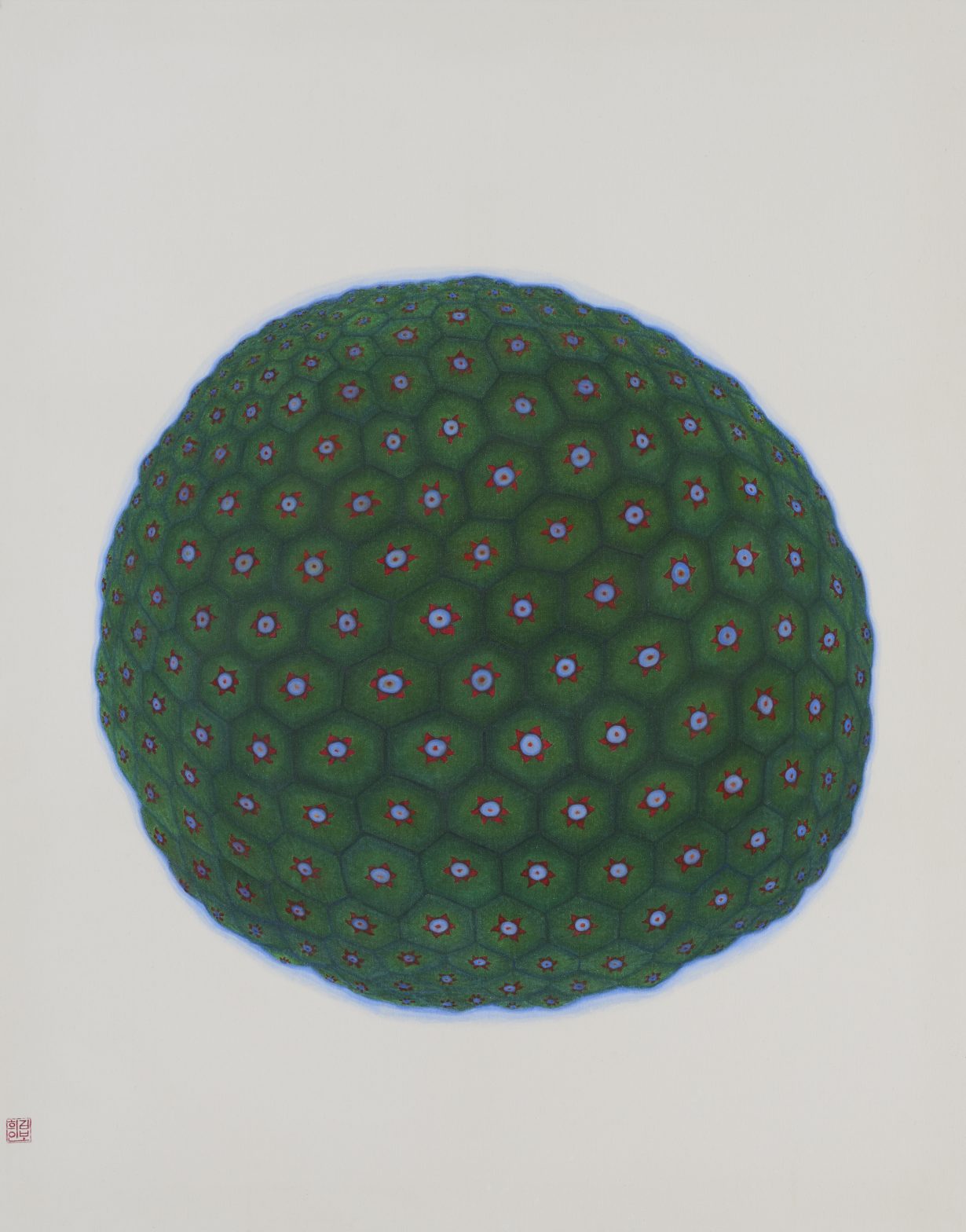

KB Looking at a sunset, I sometimes feel like this is my moment in life, its scenery sad and beautiful at the same time. There are things that I have realised over the years, and I think about relationships that are embedded in the landscape. The Jungmoon series, which I worked on from 2020, features road scenes at dusk. The road signs, such as speed bumps and ‘narrow lane’ signs commonly found in daily life, feel to me now like signals for wider moments in life: rest, pause and arrival. The recent series of paintings The Seeds (2020 –) aims to express the condensed potential energy inside seeds: the colours and various shapes aren’t based on reality, but are all from my imagination. Seeds contain both destruction and creation, and through their depiction I hope to capture some of the intense vibrancy and order of nature. Through embracing the wonders of nature and of time, I feel I have developed a sensitive and delicate approach to how we perceive our surroundings.

AR Given this relationship to the natural world, do you feel there is there a spiritual aspect to your work?

KB Just as all artists in the world dream of their own utopia, I am trying to express the wonders of nature, the joys of life that are allowed to me every day, and the gratitude for the creator in my painting. I believe that humans should ultimately get closer to nature. I hope through experiencing my work, viewers might feel the mystery and wonder of nature, the world around them, and gratitude for our presence in it.

AR Do you think the shifts and developments of your work reflect in any way the changes in Korea of the past 50 years?

KB It is impossible to say precisely, but implicitly, my work reflects changes in society and the environment. The artist is always influenced by the environment in which they work. Recently, the boundary of Korean painting has become more flexible, open to alternative materials. It is an active exchange, and just as Korean art is not limited to local meanings and impressions and can be appreciated as art and painting in and of itself, I also would like to create works that can be universally appreciated anywhere.