This collection of stories inspired by Old Dhaka depicts urban life informed by colonial histories and political instability

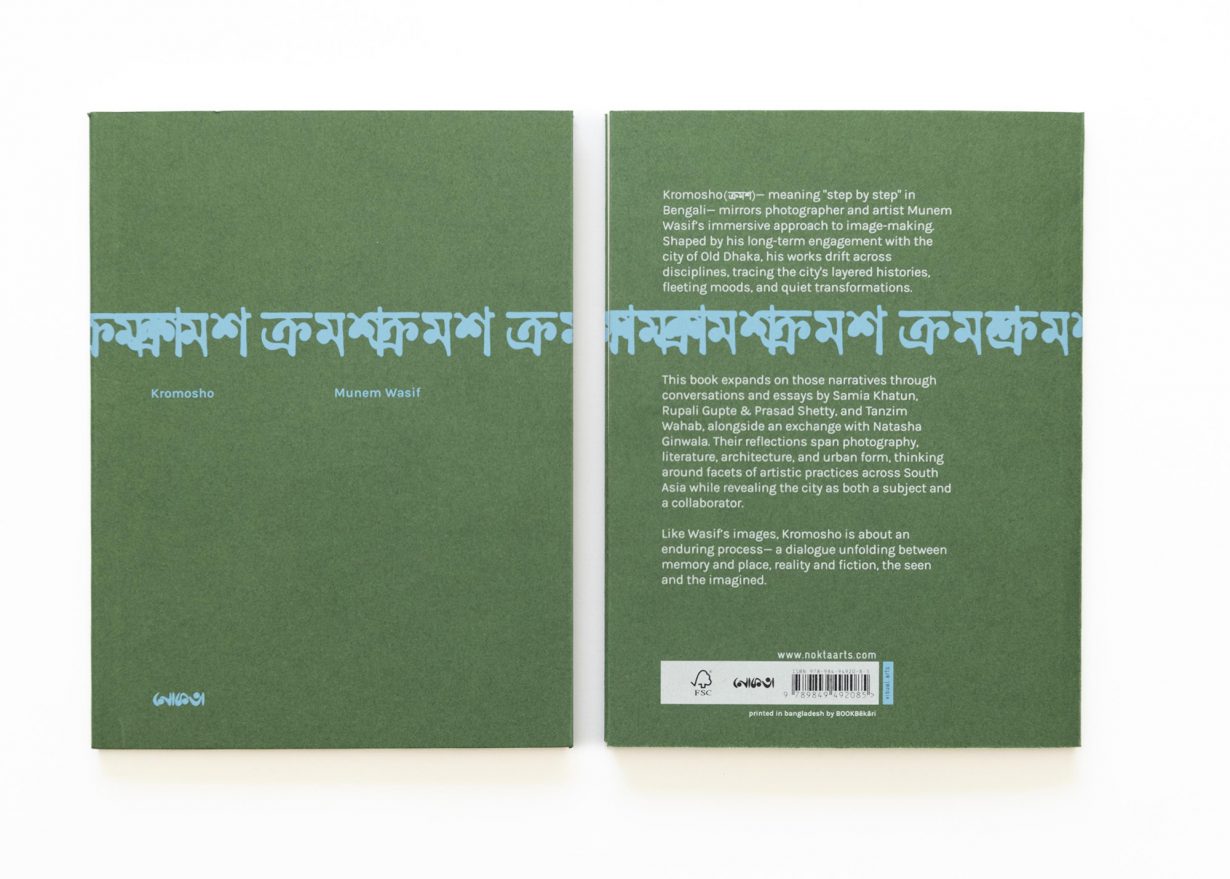

Munem Wasif has been documenting and engaging with the city of Old Dhaka in Bangladesh through photographs, moving image and installations for over two decades. Kromosho, which means ‘step-by-step’ in Bangla, is a collection of stories and thoughts about that urban environment, the livelihoods of those who engage with it and the community that those people form as a result. Wasif juxtaposes his imagery with texts by a range of collaborators: cultural historian Samia Khatun takes a diaristic approach; artists Rupali Gupte and Prasad Shetty offer a fictional intervention; art historian Tanzim Wahab provides an essay chronicling Wasif’s practice; while curator Natasha Ginwala engages in a conversation with the artist. More broadly, Wasif and his collaborators depict urban life in South Asia, and Bangladesh in particular, against the backdrop of the latter’s tragic history (being carved out of the British colonial partition of the Indian subcontinent) and recent citizen uprisings against Sheikh Hasina’s regime.

In the introduction, Wasif says, ‘while my gaze on the city evolves over time, the city in turn morphs with increasing complexity’. Stills from his film Kheyal (2015–18) accompany Khatun’s reflections on the subject matter written as she first watched it. However, as Khatun recalls her research on sites, people and specifics she sees in Kheyal, the text moves between various timelines and genres that range from mythical, epic, historical, to impossible. Reflecting, using her ‘archive’ of dreams and memories, on the presence of a white horse in the film, Khatun wonders if it could be Uchchaihshravas from the Ramayana, or Buraq, or Duldul, the mule on which the Prophet Muhammad entered the night sky.

Gupte and Shetty’s short story, ‘The Dermosonic Machine’, similarly traverses a blurry line between imagination and reality by unveiling a story of how the energetic self and the urban feed each other. Mumbai-based electronics repairman Pradeep is the quintessential middle-class South Asian citizen who works daily to achieve his own dreams and desires to reach greater heights. His innovative ‘dermosonic’ machine plays the sounds of different parts of the human body. When he realises that a British company has patented the similar name ‘Dermisonic’, he gives up, assuming that this will impact his invention. The story raises questions about the human obsession with stasis in a world that is constantly evolving. It mimics also Wasif’s references to the capacity of the urban form of Old Dhaka to, as Gupte and Shetty write, ‘allow flows of bodies, commodities, ideas, money and imaginations through it’.

Much like Pradeep from Mumbai, the people of Old Dhaka move in their psyches even though they may not move geographically. Wasif depicts these internal shifts in the series Stereo (2001–22), featuring original paper-negatives created with a box camera. Among these are my favourite markers of this urban paradox of movement and stasis. In one photograph a mother peruses her daughter’s hair, an age-old act of maternal bonding, while in another a smartphone balanced on a teacup plays a Bollywood music video. The first indicates slowness and stillness rooted in family relations, while the second emphasises technological evolution that follows fast-paced urban living. While Wasif primarily uses lens-based mediums associated with the documentary form, this publication is a means of animating his subject matter and Old Dhaka as a living city of people – full of breath, sweat, energy and movement. For Wasif, this subject matter is not merely visually but also psychologically rich, a facet of his work that his collaborators’ texts do much to bring out, in a way that the usual white-cube exhibition display would not. The result is a mobile, tactile survey of his practice that reminds us of the individual and collective psyches that form an urban environment.

Kromosho by Munem Wasif. Nokta. Rs. 1,557.00

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.