ArtReview sat down with the curator of Ghosts of Empires II to discuss diasporic communities, art economics and unexpected connections

Ghosts of Empires II, currently on show at Ben Brown Fine Arts in London (through 22 October) gathers work by 14 artists from or with diasporic connections to countries that have experienced various forms of colonialism. It seeks to explore what they share and to highlight the ways in which they have thrived and survived imperialism. ArtReview caught up with the exhibition’s curator Larry Ossei-Mensah to discuss some of the show’s themes.

ArtReview Ghosts of Empires II takes its title and inspiration from a 2010 book by the current Chancellor of The Exchequer, Kwasi Kwarteng; the exhibition features, in the main, diasporic artists – what was the motivation behind that decision?

Larry Ossei-Mensah Looking at the book and then talking to artists from Guam (a US territory and contemporary colonial asset), I began thinking about the process of building an empire – from observation, a nonscientific, non-ethnographic perspective. To do that you need to have assets, you need different people that you can draw on for labour, assuming that the production of some sort of asset is a motivation for empire.

To do this necessitates disengagement with these ‘other’ places [from which the labour is drawn], not just in economic terms, but in terms of the psychological components of empire and then the residue of it. Yesterday, for example, I was at an event launching a new spirits company based around Ogogoro, which is palm wine from Nigeria. But they’re distilling it in Scotland. And at the launch they were talking about what the British did to demonise indigenous spirits in order to get people to drink British gin.

For me, these different moves and tactics, and the byproducts of these moves and tactics, still live with us. Their residue can be quite amazing. Take the Notting Hill Carnival: the act of carnival is traditionally an act of resistance. Now, in Notting Hill, it’s a celebration of the Caribbean culture, but also a British tourist attraction. How do you navigate the balance of celebrating an ’other’ culture, and working on an event that’s now part of the UK calendar – that’s been coopted into British culture?

AR On the flip side to that, it’s often the case that diasporic communities hold on to an image of the place from which they or their ancestors migrated that bears no relation to the contemporary realities of that place. Anuk Arudpragasam writes rather eloquently about that in relation to Sri Lanka in his novel A Passage North. Particularly about how when, say, diasporic overseas Sri Lankans who have become, in many instances, wealthier than people living there, put together funds to ‘save’ things that are no longer a part of contemporary reality.

L O-M My hope is that these types of projects begin a conversation that might really get to the root of issues regarding where support is needed. It’s not necessarily about saving things. I think if you live there you’ve figured out survival mechanisms.

How do you create a more thoughtful approach? I think sometimes if you are from the place, there’s a danger of thinking you’re above reproach, but then there’s also the effect of living in another place, where you’ve assumed that place’s ideology, maybe to a degree, its behavior, it’s moment for exposure. How do you heighten that awareness?

AR How do you think arts or artists do that in ways that are, maybe not better, but different from literature?

L O-M I think, firstly, it’s more tangible, the possibility of seeing something and connecting to a memory. It could be triggering; it could also be a reminder of something that you’ve forgotten. I think it’s the sharing of perspectives and imagination that’s less hampered by political guidelines – and it’s something you wouldn’t necessarily be able to have in an academic sphere where it’s usually academics talking to other academics. Whether it’s a project in the gallery, something in the street, something in the community, there are so many more possibilities of touching the people who need these reminders or outlets. And that leads to the second point: that art allows the possibility of exerting some agency around your own narrative.

AR Maybe one of the risks of placing these narratives and conversations within the sphere of art, is that in some ways it’s outside the reality of those narratives.

L O-M I think sometimes you need that step out of reality to imagine another possibility. Sometimes within a particular reality and depending on how people think, you may not know what is possible, that your situation can change. For me, that has always been the power of art: I love it when I have this very rigid way of thinking about something; then I go see a show or I talk to an artist, or participate in some type of social practice initiative, and everything I was thinking just goes out the window.

AR If we focus on an artist in the show, Theaster Gates, to some degree, for him, the economics around arts and the commerce around art has always been as important as the art itself as a tool for changing things.

L O-M I think about what he’s been able to do with Rebuild, in terms of taking a section of the south side of Chicago, that basically, if it were left in the hands of the city, would just be derelict. He uses his urban planning background, but then also his organizing and artistic background, to essentially reinvest resources into the community and create jobs.

AR Some of which relies on leveraging his position within the art market.

L O-M Yes. 10 years ago, we might have frowned upon that. At the end of the day, they have resources, they have skills, they have human capital that’ll help these artists to then go back into their community and give them the tools to add value, whatever that may look like. I think it’s only for an artist to really think: OK, we’re going to take this super capitalist structure and figure out how can we turn it on his head and make it of use to other people. I think if that was, say, a social worker – unless they’re super radical – then there are rules or a protocol that they’ve got to abide by. I think it’s the freedom and that behavior, imagination and execution – depending on the initiative – that will always give artists space to operate differently.

AR How did you select the artists in the show?

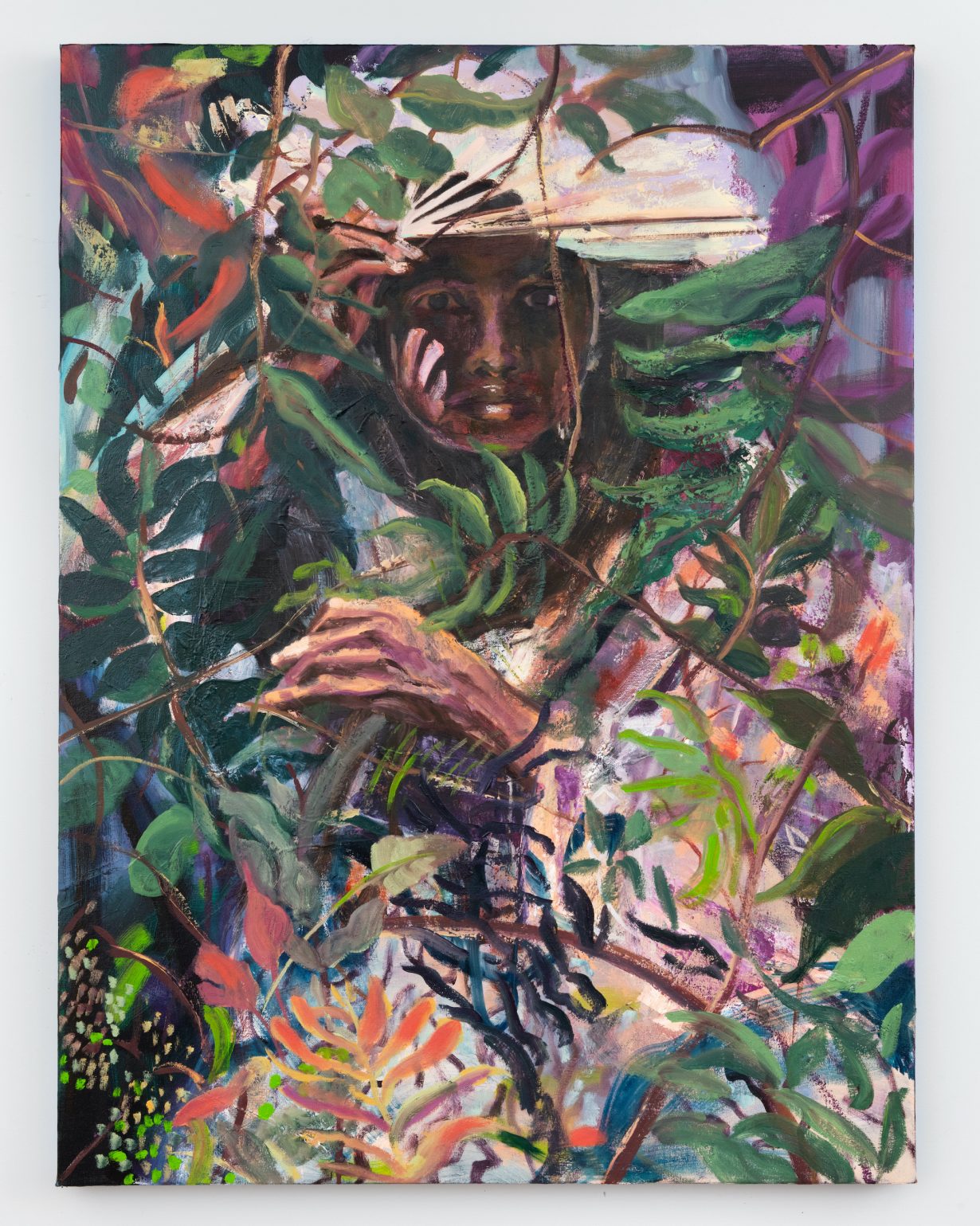

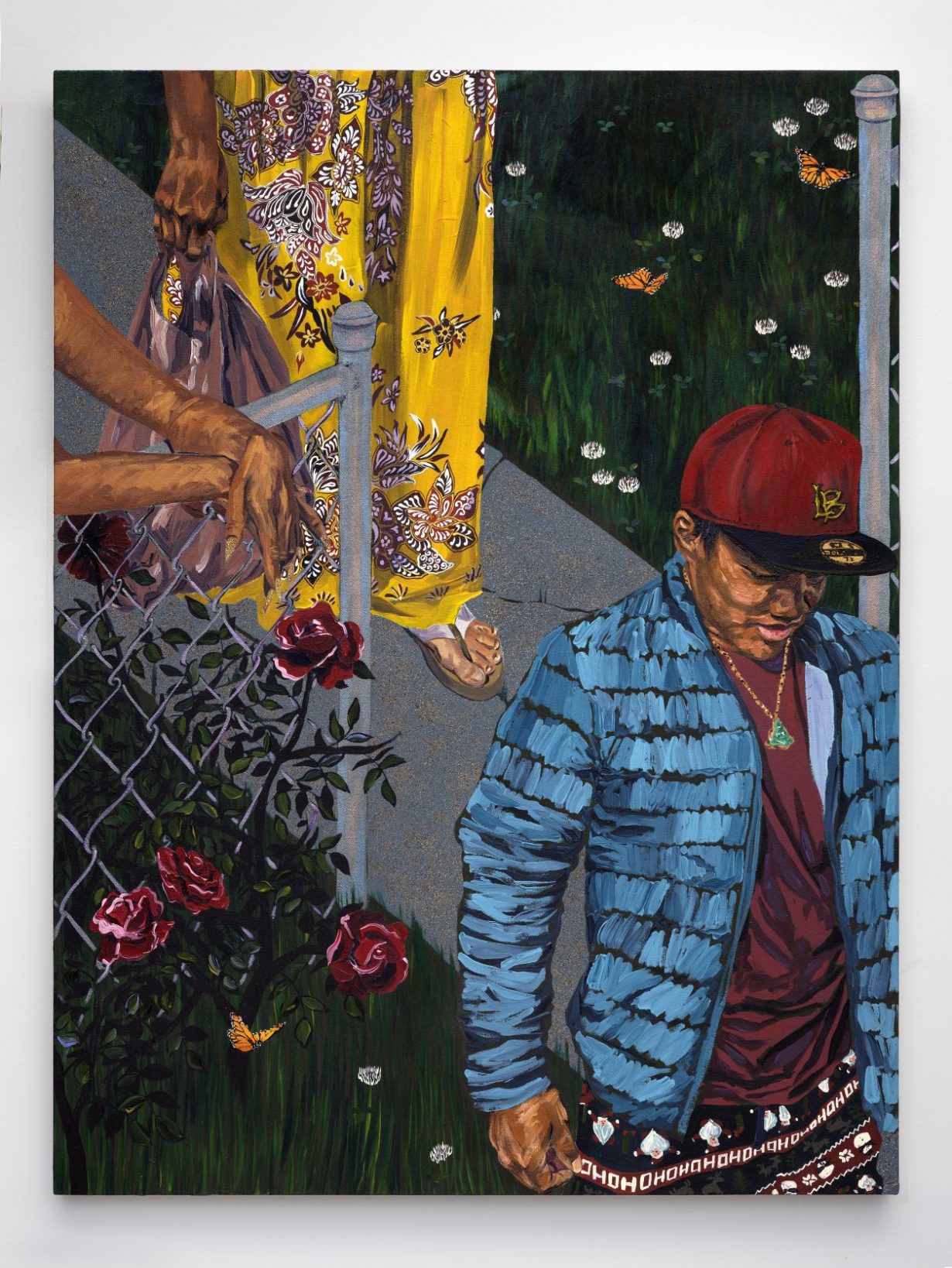

Larry O-M It was a mix of my own research and talking to people about the idea. A lot of the recommendations came from other artists. Tammy Nguyen recommended Adam De Boer. Didier William was another artist that I talked to – he’s Haitian but based in Philadelphia. He was instrumental in expanding the purview. Initially it was going to focus on the African diaspora. He said, that’s a cool idea [for a show] but what value does that really add given what was happening in the United States – and still is happening with a lot of the assaults against AAPI citizens. So the project evolved into a question of how to help center those communities in this conversation. We’re all dealing with very similar challenges, to different degrees, but what happens when we start thinking about each other in solidarity.

AR Is that also a reaction to the fact that art discourse is generally dominated by the US and Europe? Another Empire of sorts?

L O-M Of course. And how do I use that as a device to open up a broader dialogue, which wouldn’t always have happened, I guess, in a more mainstream context. If we’re putting it plain, the art world loves black artists. Or artists from the African diaspora. Great. I was just discovering all these incredible artists from the Asian diaspora who had something to say. Take Tidawhitney Lek, who’s Cambodian-American and grew up in Long Beach. I’d be in the studio with her and she would just speak up these stories about her family, and I’d be thinking, ‘That sounds like my family’. Without sounding hokey, how do you get people to see the humanity in these other cultures?

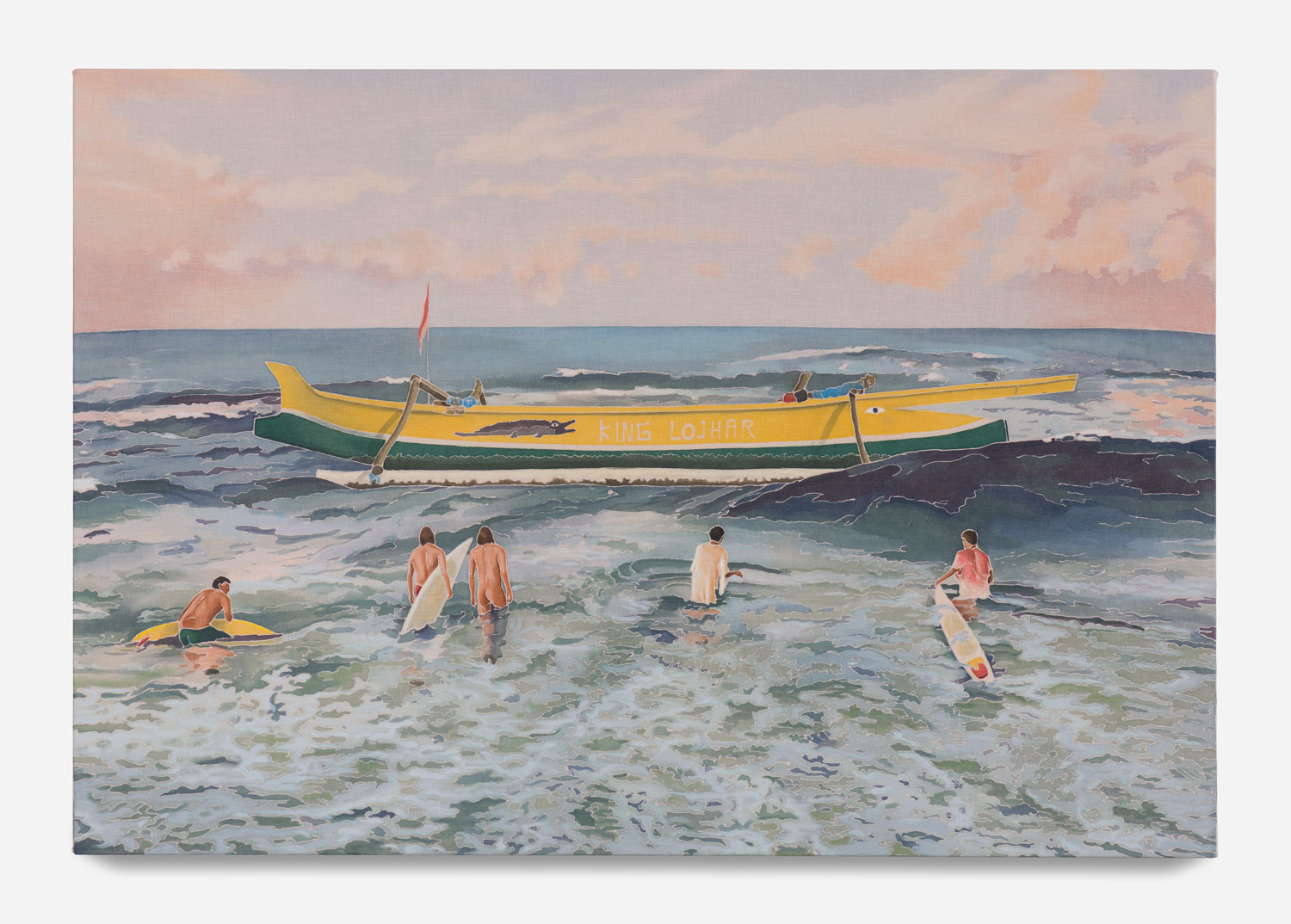

AR At the same time there are specifics. You have two Filipino/Filipina-American artists in the show – Jeanne F. Jalandoni and Maia Cruz Palileo. The relationship of the Philippines to America is quite specific: over history claimed by America, bombed by America, ‘saved’ by America and had a revolution against America.

L O-M I think that’s the interesting thing. (And let’s not forget the Spanish interest here.) It becomes a way – for me, when you’re thinking about it from an American lens – to implicate our participation, because a lot of times Americans are like, ‘Oh, the English did this, the French did this, the Dutch did this, the Italians did this’. I’m like, ‘The Americans are doing this. Have been doing this, not only on our soil’.

AR Do you have any concerns about tackling these subjects in a commercial gallery space?

L O-M My track record has always been about trying to use the platform to introduce new voices. Obviously, we have established voices, so how do we use them as a carrot to attract people to see the show? Then hopefully there’s a discovery, and then hopefully there are these connections. For me, the other thing that is always exciting about a show is a connection that I don’t see that you may see. Just by proximity of one object next to each other, or by getting more insight and background about an artist and you being from a place and saying, ‘Oh my grandfather also used to make boats’, or something like that. I know that learning is not always necessarily part of commercial shows, but there are those moments that, for me, are very gratifying.

Ghosts of Empires II at Ben Brown Fine Arts, London, through 22 October