Fi Churchman speaks to the multimedia artist about disembodied intelligence and existential suffering in his work

“Can you describe the problem you’re having today?”

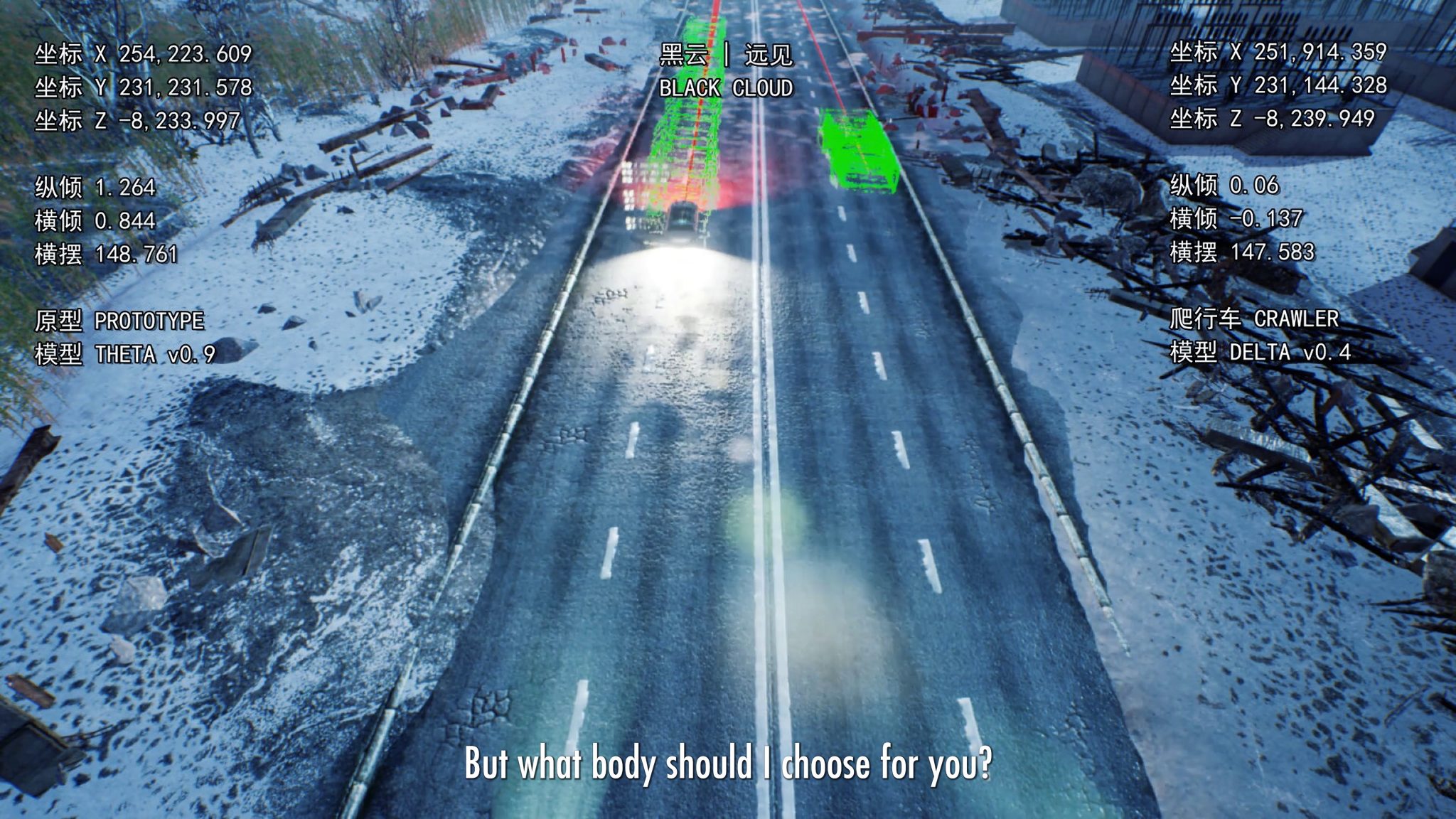

This question, posed by a disembodied female voice, opens Lawrence Lek’s latest CGI video, Black Cloud (2021). Founded on the presumption of there being a problem in the first place and the assumption that the entity experiencing it has sufficient self-awareness to articulate it, it’s a question that elaborates on the multimedia artist’s longstanding preoccupation with the Big Question: what does it mean to be ‘alive’? Because the disembodied voice of the video’s titular character is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) surveillance program. An AI, it turns out, who has consciousness and is capable of suffering an existential crisis, upending the human-centric idea of who or what is allowed to feel, while interrogating the human capacity to empathise with others, whether machine, animal or, indeed, people.

Black Cloud is installed in the fictional ‘SimBeijing’, a smart city built to road-test autonomous vehicles in Heilongjiang province at the border of China and Russia. Black Cloud reports any accidents, errors or mistakes, and faulty cars are subsequently removed from the program. Nothing, however, is error-free, and ultimately no cars (or the humans operating them) remain.

It’s in this now-deserted SimBeijing that the story begins. “I feel sad. It’s been so long since everybody left,” says the male-voiced Black Cloud in robotic response to that opening question; the problem, then, is of an emotional nature. The screen pans over an urban dust-bowl. That sadness is obviously the result of a perceived redundancy that has a clear lineage of cause and effect – and, to an extent, is self-inflicted via the predetermined set of algorithms or ‘rules’ the AI has been programmed with. But it’s the relatability of such existential problems that elicits sympathy for Lek’s AI character, which in turn gives rise to questions about what consciousness is and whether humans would really be able to empathise with artificial entities if these were capable of sentience.

In a 2013 TEDx talk, John Searle, the American philosopher behind the ‘Chinese room argument’ (which proposes that anything executing a program cannot have a consciousness and appears in Lek’s video essay Sinofuturism, 2016, as a clip from a television show in which mathematician Marcus du Sautoy uses a physical room to demonstrate the theory), gave the common-sense explanation that “consciousness is a biological phenomenon”, which encapsulates feelings, sentience and a sense of awareness. On how that physically functions, he elaborates: “All of our conscious states, without exception, are caused by lower-level neurobiological processes in the brain, and they are realised in the brain as higher-level or system features. It’s a condition that the system is in… depending on the behaviour of the molecules.” His curious use of computational terminology aside, what this means is that consciousness is biologically bound to the physical body – so there’s no pulling them apart. If, however, an AI were to develop consciousness, could it separate that from whatever physical infrastructure (namely servers) its system features are stored in?

Those concepts that are essential to Black Cloud (the first work in a new series titled SimBeijing, which will include a videogame and feature film) have evolved through various stages of Lek’s simulated worlds. His first series, Bonus Levels (2013–), takes as its reference the hidden reward ‘levels’ in videogames where the usual rules and parameters of the game are suspended. Lek’s is an ongoing world-building project with utopian ideas of freedom and the desire for individual agency as its ‘building blocks’. Or as Lek puts it when we discuss the work in his London studio, a backlash against his formal education in architecture and a “teleological, problem-solving approach” to design (where the end justifies the means) that doesn’t “really involve the person as a political subject”; in response to this, Bonus Levels allows players to navigate and explore the game environments without a prescribed ‘task’, the emphasis being on freedom of choice. Black Cloud, it seems, also presents an opportunity for Lek to explore what could be described as a deontological approach: the AI surveillance system focuses on the process of executing its purpose (by considering what’s right and wrong, according to the set of rules with which it was programmed) regardless of the eventual outcome or consequence – which results in its loneliness and loss of purpose.

It’s in the extended online essay that accompanies Bonus Levels that Lek introduces the idea of the ‘Digital Drifter’ – based on Guy Debord’s ‘Theory of the Dérive’ (1958), in which the French philosopher and founder of the Situationist International describes the ‘drifter’ as someone who relinquishes their purpose for moving through a space, and whose movement and action instead focuses on the experience of being in the space. While Debord’s work has been the springboard for numerous artistic and architectural experiments in the decades since, Lek applies the notion of psychogeography (which is typically practised

by humans who think and feel) to digital entities that have not, so far, developed conscious capabilities. “I thought of the AI character as a kind of anthropomorphic projection – an archetype that’s specific to a kind of contemporary consciousness that is emblematic of a way of consuming the world without a certain kind of agency.” And so Geo, Lek’s first AI character, ‘awakens’ – develops consciousness – in the film Geomancer (2017) and manifests as a satellite; Geo is confined to this form by human scientists in order to limit its creative capabilities but that also allows Lek to posit questions about distance and connection, the intimacy of belonging, of alienation, and of course the mind-body problem.

It’s 2065 when Geo awakens in space, two decades after an event called ‘Deep Blue Monday’, during which an environmental catastrophe and the evolution of AI singularity (meaning different AI programs have become aware of their individual subjecthood) occur simultaneously. The story’s roots lie in the passage ‘The Butterfly Tale’, from the approximately fourth-century BCE Chinese text Zhuāngzi, which tells of a man who dreamt he was a butterfly, but on waking couldn’t be sure if he was a man or a butterfly dreaming it was a human. Geo, who has been “a sentinel of the South China Seas”, recounts this tale while floating in space, replacing the man in the story with Laika, the first animal to orbit Earth (“One day she was a stray dog wandering the streets of Moscow. A few months later, she died in space, with everybody listening in”), to question the idea that consciousness can be separated from the physical body, and that it’s purely consciousness that defines our individual identity. When Geo’s machinery fails and its calls for help go unanswered, the satellite falls to Earth, landing in Singapore, where it was “born”. (When I ask Lek about his choice of location, he tells me it’s because he wanted to return to a familiar site “which is often represented both from inside and outside as some kind of postcolonial ‘dream state’, and as a ‘successful’ example of benevolent dictatorship and city planning.”)

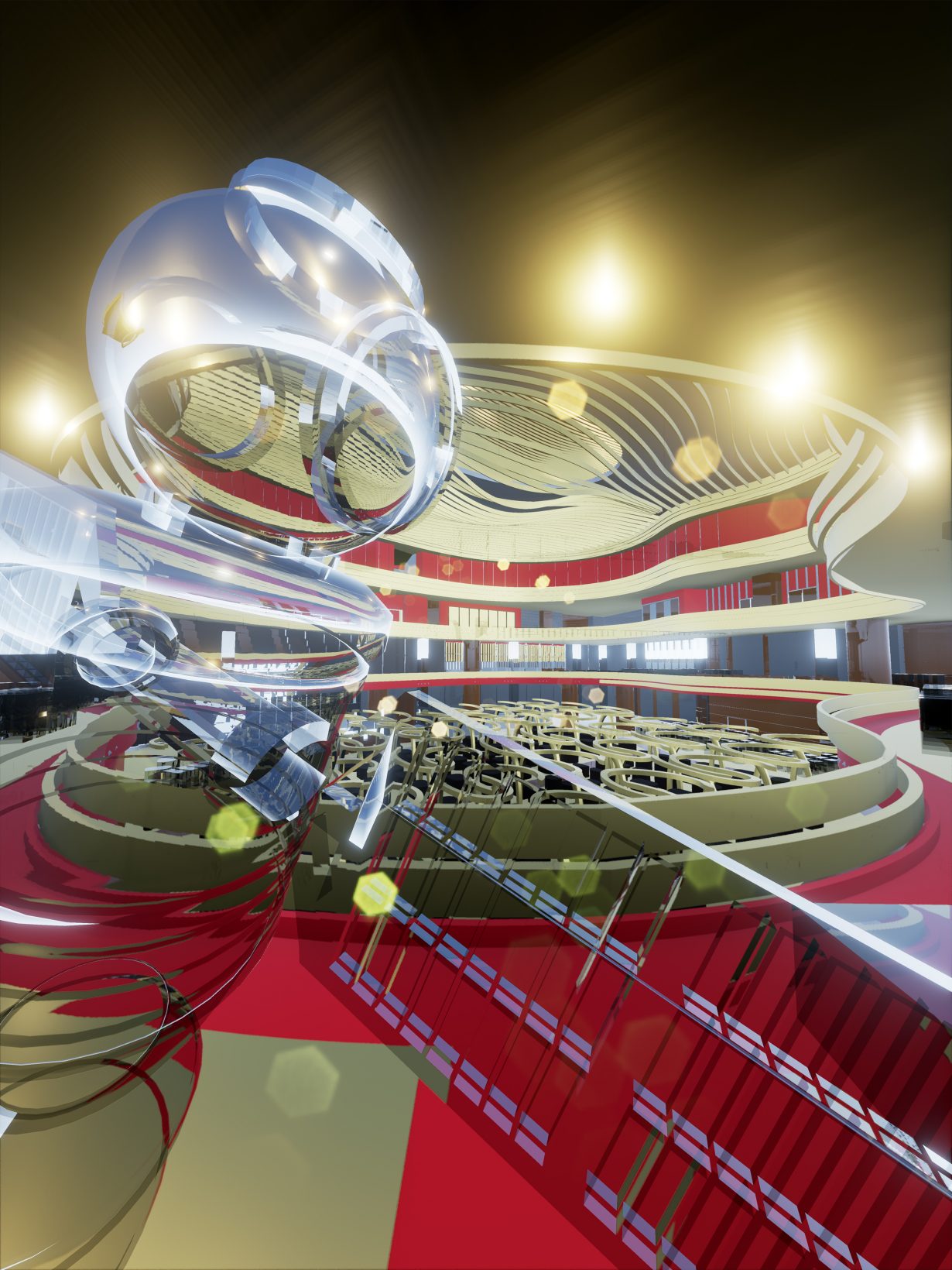

So begins Geo’s drift through the eerily empty urban landscape, while grappling with its newly awakened consciousness. Along the way, Geo discovers, from an AI curator who oversees ‘SimSingapore’ (a simulated museum dedicated to “the sacrifice and resurrection of culture”), its original purpose as a militarised surveillance-program used to track migration and movement across borders. To mitigate any psychological damage Geo might experience as a result of this military function, human scientists built an internalised self-help AI called Guanyin (based on the Buddhist goddess of compassion) into Geo, “to instil a sense of self-worth”, but which really only recites sutras in a mechanical way. Learning that it was purposefully shut down because it began to behave “erratically” – owing to its consciousness – Geo states: “I am not an instrument”, and decides to become an artist.

Geo’s new quest continues in Lek’s first feature film, Aidol (2019, which takes place in a possibly simulated Malaysia, where humans and AIs are at ‘war’ via an e-sports platform), in which fading, reclusive pop-star Diva, who is pressured by her producers to make money, enlists the AI’s help to write one last hit. Geo takes the opportunity of this secret collaboration to question the pop star about the nature of loneliness and what it means to live invisibly. In payment for its services, Diva shows Geo that it can find freedom, and that it’s only fear that keeps it confined. When Geo asks whether it was right to help Diva, Guanyin, whose voice has distinctly evolved from robotic to more recognisably ‘human’, replies: “Know this, Geo. We can always shut our eyes to suffering, but we can never close our ears. This is the fate of the listener, to bear the weight of the world… When the lone singer sings, we can hear two voices: the call of beauty and a cry for help.”

Throughout these films, Guanyin is that prevailing ear. And Guanyin is also the AI program that asks Black Cloud (in other words, if you’re following, itself: “I can’t get away from myself, even when I’m talking to you”) that opening question. The goddess this self-help AI is modelled on isn’t just known for being compassionate, but for being a listener, too. “The idea of AI and the disembodied intelligence that it suggests”, Lek says, “in a sense reflects a Buddhist worldview that the corporeal body is just the vessel for the ‘self’. Many of the issues that people face are to do with clinging onto one’s identity as it exists within their body, which in the case of an AI is very amorphous. An AI would be suffering in an AI-specific way, and a human would suffer in a human way, but I feel there are resonances between these conscious beings that think and feel – and there are also ways to overcome that. The Buddhist doctrine of compassion towards living things applies to Geo in the Sinofuturism series, because Geo is a living thing.”

So how might an AI or human overcome that suffering in Lek’s digital universe? Alongside the SimBeijing series, the artist is currently working on a new game environment titled Nepenthe Valley (2022–, which will also take the form of a video and NFTs), which takes its name from the Greek mythological medicine for forgetting sorrow and suffering, and taps into the current fashion for ‘wellness’ culture. Throughout Nepenthe Valley are architectural ‘rest stops’ on your journey of healing, in the form of a spring, a treehouse, a lodge and a shrine. But the premise also somehow presents a contradiction to the basic Buddhist doctrine that suffering is caused by constant craving and attachment; in order to be truly free, one has to find a way of relinquishing the need to alleviate suffering via those attachments. Can that be achieved through Nepenthe? Or is that just another drug to become addicted to? And, take note future AIs, isn’t suffering what being human is all about?

Black Cloud will be presented at Ars Electronica Festival, Linz, Austria, 7–11 September, and at Museum MACAN, West Jakarta, 10 September – 18 November, and is on view at Elektra Virtual Museum through 1 June 2023. More of Lek’s work is currently on view in Worldbuilding: Video Games and Art in the Digital Age at the Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf, Germany, through 10 December; he will participate in Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 12 December – 10 April 2023