The two artists reflect on how their distinct political realities, in Asia and in Europe, have led them on a journey that has seen their paths converge in unexpected ways

In 1971 Korean artist Lee Ufan and French artist Claude Viallat met for the first time. They were born in the same year, had both recently played pivotal roles in the generation of artistic movements (Mono-ha and Supports/ Surfaces respectively) that would have a major impact on the direction of art in Asia and in Europe. Upon meeting, both were surprised by the similarities between their respective approaches to artmaking, encompassing a radical rejection of traditional techniques and a new approach to materiality.

This month the pair are artistically reunited in an exhibition titled Encounter at Pace Gallery London, curated by Alfred Pacquement. Marking the first time the pair have exhibited together, the exhibition offers an opportunity to consider the ways in which artists working in different contexts, societies, political realities and geographies might come up, independently, with parallel approaches to artmaking. ArtReview Asia spoke to the artists, via email, to consider whether or not the nature of the journey changes the destination.

Materiality

ArtReview Asia How did you first meet each other? Were the analogies between your two bodies of work evident from the outset?

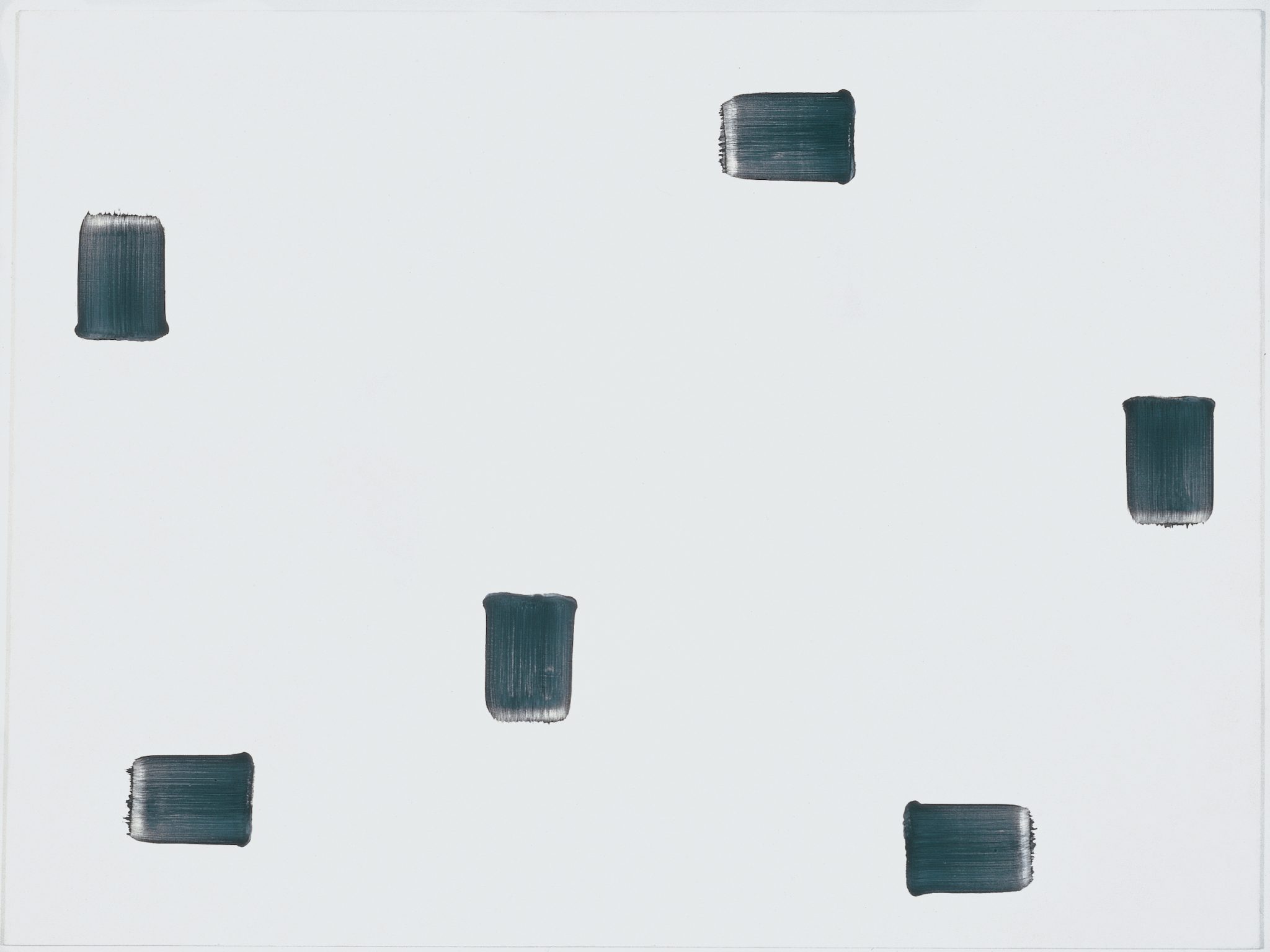

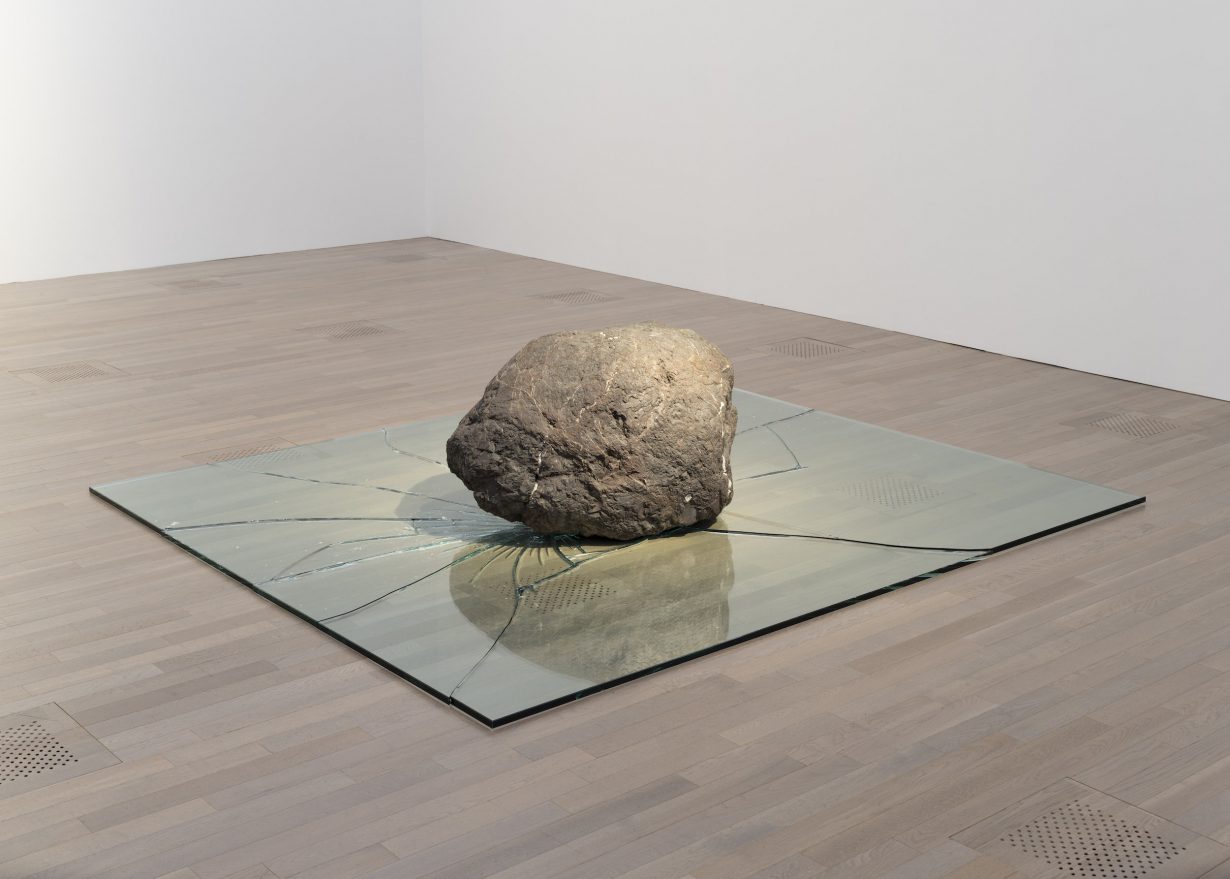

Claude Viallat The first time I came into contact with Lee Ufan’s work was at the Biennale de Paris. The group Mono-ha [of which Lee was a member] showed at the Parc Floral while, with Daniel Dezeuze and Patrick Saytour [both of whom, alongside Viallat and others, were members of the group Supports/Surfaces], my work was on show at the Musée Galliera. The first works I saw of Mono-ha immediately struck me as very significant. Among others, a repetitive painting on the wall and a glass sheet exploded by a rock placed on it intrigued me, and I was particularly interested by an artwork made from a net. The net was attached onto the walls on all sides, whereas its centre was left slack touching the floor, forming an inverted pyramidal shape.

Lee Ufan It’s important to note that both of our approaches to art are based on external materiality and physical acts. We also have in common the repetition of the same patterns in our paintings to represent infinity.

ARA What is it that attracts you to each other’s work?

CV I always like the feeling of being in a process. After we had met several times, being invited to Japan by a gallery, I visited Lee at his home in Kamakura. This must have been in 1973 or 74. On this occasion Lee showed me several works comprising rocks on steel sheets, together with some paintings bearing very marked, repeated brushstrokes. I noticed a real relationship between the materiality of our works.

ARA Lee Ufan once said of the relationship between your works: ‘It was undoubtedly the first time in the history of art that, concurrently, in different geographical locations, analogous tendencies were born.’

CV I absolutely agree with Lee’s statement; I also find this situation exceptional. We come from completely different cultures and still, in different locations, at the same moment, hit upon a system, a system that is an agreed, commonplace but very strong system. And each of us uses this system as an element of communication, incorporating all the demands and analytical potential it suggests and can support. And this tendency even goes beyond Supports/Surfaces and Mono-ha. I distinctly recall an anecdote I find interesting in this context, because it illustrates at the same time both Lee’s quote and the novelty of our artistic approach.

In 1971 I brought the first ropes with knots to my gallerist Jean Fournier. He was very surprised, as this was very unusual at the time. He emptied the bag onto a stool. He also took a rope and arranged it in a sort of staging on a low table. Leaning back, he visualised the arrangement on the table and the stool with the ropes, exclaiming, “How beautiful this stool is!” Immediately afterwards he corrected himself: “I have said something I shouldn’t have. I have made a flower bunch out of a rope rather than looking at it for what it is.” Some weeks later, just before leaving on holiday to the seaside resort La Rochelle with my family, I brought works made with nets to Fournier. Walking on the pier in La Rochelle, I chose one of the numerous postcards picturing a fishing net and sent it to Fournier with greetings.

The next time I went to the gallery, Jean Fournier’s assistant asked me whether I had seen the latest edition of Artforum they had sent me. To which Fournier answered, “Yes, of course Claude has, he sent the postcard”. I had indeed received the edition of Artforum before my holidays and noticed an article on Robert Rohm, an American painter working with nets. I was very intrigued to see an American artist working with nets at the same time as I was and also at the very moment that I discovered the net at the Mono-ha exhibition. It is also interesting that my postcard, which was sent without any wider intention on my part, became an indication for the gallerist that I had, on the one hand, accepted the fact that I was not the only one working with nets and, on the other, made a point in underlining, by choosing the picture of a fishing net, the fact that the net is a very ancient everyday element.

LU For my part, I think that during the late 1960s art moved away from its inner self and embraced the externality of materials and actions, which is a commonality in world history.

Neutrality

ARA What do you think were those ‘analogous tendencies’ and how, separately, did you arrive at them?

LU I would see this trend as the result of the end of the logos-centred era; and the search for new expressions, such as the presence of materials, the neutrality of actions or the repetition and multiplication of the same patterns.

CV Coming back to Lee’s and my own expression as part of these tendencies, I see the repetitiveness of Lee’s pictural work and the very strict way in which he plays with the form on the surface of the painting. But the tension he brings to his work through his way of applying colour is not at all similar to mine. I have a very detached, offhand way of painting, whereas I see the preparation, the concentration and the mastery of the relationship between the form and the format in Lee’s work. This seems extremely important to me. For me there is no relationship between form and format; rather, any relationship that happens on the surface is fine for me.

Also, my work with the knotted rope and the deconstruction of the painting relies on the knotted rope as the primal element of my confrontation with the fabric. The work with the knotted rope relates to the net, relates to weaving, to the sailor’s knot. The knot is an ancient and universal element. By enacting a kind of hypertrophy, the knotted thread is the knotted rope with all the symbolism it carries and all the usages it allows for. At the same time there is a very important analogy for me between the mesh of the net, the empty space created by the mesh or a crushed knot, and the form I use in painting. The cutting of the fibres, as well as the knot of the fibre in itself, is a universal system of repetition, and a primal memory.

ARA Do you think that the different ways of reaching the end result make the end results different, however analogous they might be?

LU Even with similar ideas, using different materials, methods or attitudes lead to different results.

CV A difference between us, as I see it, lies in the symbolism which is apparent in Lee’s work. I can see an intellectual approach in his work and his inner self expressed in his art that strikes me as very important. I, on the other hand, am impulsive in my work and, I would almost say, with me, the impulse is everything. Notwithstanding this marked difference in our approaches, I believe our intentions to be very similar.

I think that Lee’s quest integrates all the primal elements, the primal memory, and it is this quest for origins that allows an artist to go as far as possible. And one of the simplest and most symbolic acts is to throw a rock onto a glass sheet and completely shatter it. It is an act that cannot be undone, that can only be done once in this specific way, giving this specific result. This strong and material act allows for no reconstitution. It is certainly this elementary force, an elementary force charged with symbolism, that I am interested in. For me, this is essential in Ufan’s work. This and the transcription and the parallelism he creates with the brush soaked in colour and placed in a certain way on a limited surface, at the same time taking into account all the elements of marking by painting. I find this to be very close indeed to my own work.

Repetition

ARA Can you explain the role of repetition in each of your practices?

LU Repetition is never mechanical. Repetition becomes possible by making it better, newer and endlessly different. That’s why great repetition is always fresh. Likewise, our everyday life is not boring because of the subtle differences.

CV Repetition is the most ancient, most banal, most universal, most simple and direct system, even in our everyday gestures. Our whole being is marked by repetition, and for me there exists no system which is more universal and synthetic. What I am also interested in is that repetition, however done, comes out as it should. This without giving room to taste, fantasy or nicety. It is at the same time mechanical and evident.

ARA Do you think in some ways that both of your works have been about collapsing the boundaries between ‘the world’ and ‘the world of art’?

CV I think it would be pretentious to say so. I am rather in my world of painting than in the world of art. The business side of the world of art for instance is not my concern at all. I work because I want to work and my work is what I am interested in.

LU An artwork is something that is done on an extraordinary level, and it checks the ordinary. Sometimes it breaks some boundaries, but rather it makes us see this side and that side.

Absolutes & Ambiguities

ARA Philosophers such as Byung-Chul Han have suggested that the basis for Western philosophy and the thinking of the East is fundamentally different: an embrace of presence in the West and absence in the East. Is this something with which you both agree?

LU The comparison of the East and the West generates many versions. It is also an attitude to see the East and the West in terms of presence and absence. I believe that ontological metaphysics has been replaced by ego-centredness, and relational phenomenology has emerged as the un-being. In that sense, there are no absolutes but always ambiguity in the East.

CV Lee’s culture and his philosophy are certainly very different from mine. Having said that, and without commenting further on your philosophical reference and Lee’s position, I can say for myself that I am transported by the sensuality of things as well as the universal aspect and the expansion, the potential of the work. I deal with these aspects in my own way, relying on my knowledge and my experience. In that way, rather than a symbolic charge, I am looking for the potential, the openings provided by my art and the making of it.

My painting is not symbolic.

There is also the question of religion. I feel a religious dimension in Lee’s art which is not really the case for mine. Even if it is true that my Protestant origins play a role, it seems to me that it is rather an anarchic side of the Protestant faith which flows into my creative process. One could almost say that I do this in an extravagant way, maybe even in an inconsequential way. Unless this could itself be defined as consequential!

ARA Both of your bodies of work have been defined, at one time, as a battle against ‘convention’. Is this still the case now, when you have become a part of conventional art history? (Which, in itself, is something beyond your control.) Does that change the way you work in any way?

CV It is clear that the work, once in existence, becomes conventional. Going from there, all work plays with the notion of the conventional in order to become unconventional. My work as an artist consists of pushing the limits of what can be done, each time trying to reinvent or to go beyond our present moment. Of course, this defines my own attitude and I would not want to comment on others.

LU An artwork is a living thing, so it is in the process of time. I started as an artist in the late 1960s. It was when an era was collapsing and a new dimension was being explored. So I rebelled against conventional values and started anew. Today, a new era has not yet been established.

CV I think I am honest in saying that being recognised as an artist does not count for me. It simply doesn’t touch me.

ARA Given your long-term friendship, why has it taken so long for you to exhibit together?

CV We know each other but each of us lives in his own specific sphere. I, for one, live in Nîmes and only travel if necessary. It was only a year ago, in April 2022, when Lee and I met again at the opening of the Hôtel Vernon [home to a permanent display of Lee’s work] in Arles, that the concept of a common exhibition started to take shape.

LU Indeed, friendship and joint exhibitions are not related. We just wanted to do a joint exhibition because we are old.

Lee Ufan and Claude Viallat: Encounter is on show at Pace Gallery London through 29 July