© the artist. Courtesy the artist and MCA Australia, Sydney

The failure to belong to a culture is often framed as a personal shortcoming. But for Lindy Lee, the perspective of an outsider can lead to acts of artistic generation and open the door to truths you don’t yet know.

The Australian-Chinese artist grew up in Brisbane, Queensland, during the 1950s and 60s, before the end of the White Australia policy, the regime that restricted immigration from non-European countries for nearly seven decades. Although she once yearned to fit in, she now believes that embracing her otherness is a source of rich creative power. “You know how it is in the schoolyard, when one has a face that is different,” says Lee, now in her sixties, a note of wistfulness in her voice. “But if you have to grow up on the fringe of something, or if you are straddling things, you are forced to understand worldviews in different ways. It might be painful, but it is your gift.”

Moon in a Dew Drop, the largest survey of the artist’s 35-year career, is about to open at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. It comes during a moment in which Australian institutions are grappling with the questions of representation and power that are driving the wider artworld. A survey exhibition from an Australian woman of colour is still an all-too-rare occasion. The show, which features over 70 artworks from the 1980s to the present, is a study in the depth and intricacy of the artist’s vision. Lee, who is widely considered one of Australia’s most important contemporary artists, has been exhibiting nationally and internationally for the past three decades, showing everywhere from Japan and Malaysia to Canada and New Zealand. She arrived on the scene during the early 1980s, an era that saw Australia start to publicly question its national identity, galvanised by the 1988 bicentenary, the 200-year anniversary of the arrival of British colonisers in Sydney.

She was among the first Australian contemporary artists to grapple with European art history, going on to invent a visual imaginary that could articulate the complexities of diasporic experience. Lee, who taught at the Sydney College of the Arts for over 20 years, influenced a generation of younger artists (including Jason Phu and Phuong Ngo) who have been emboldened by her example in the process.

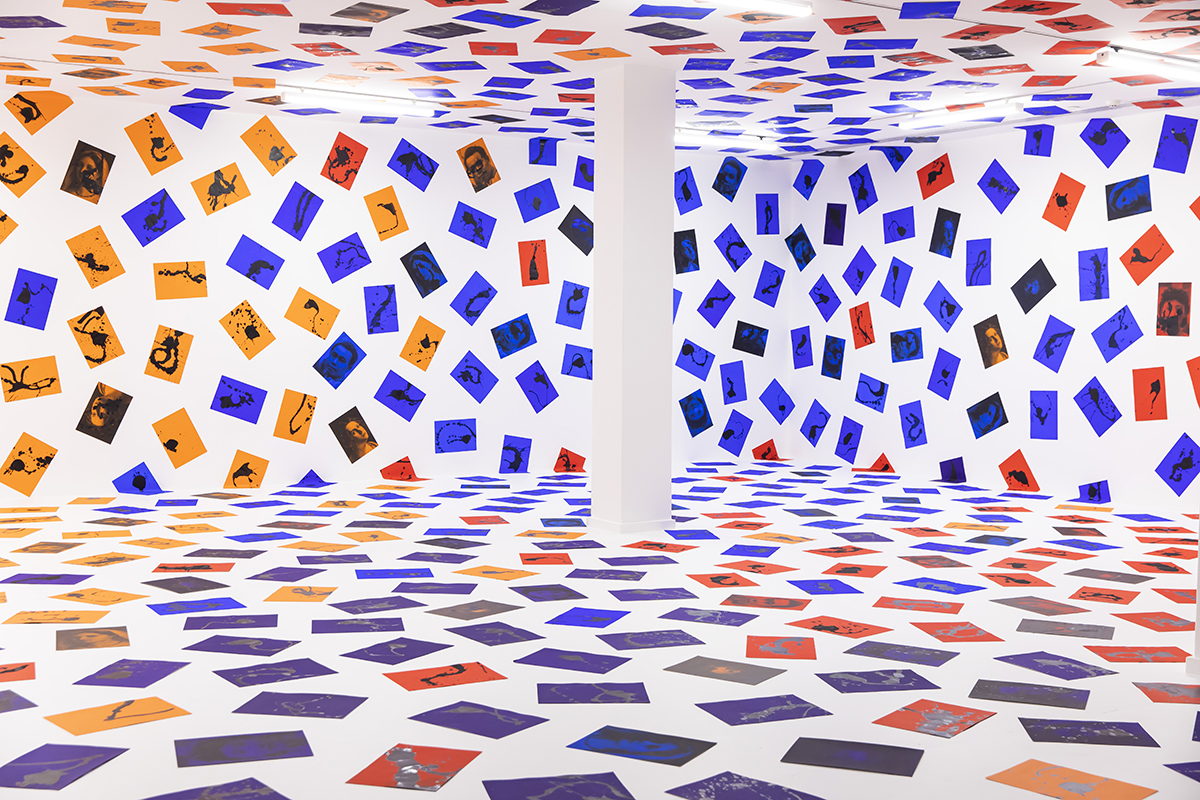

Lee, wearing hot-pink sneakers, her blunt fringe swept off her face, emanates excited energy. The artist is deep in work mode. Today, she tells me, flopping down on the floor to sit cross-legged, she’s installed No Up, No Down, I Am the Ten Thousand Things.

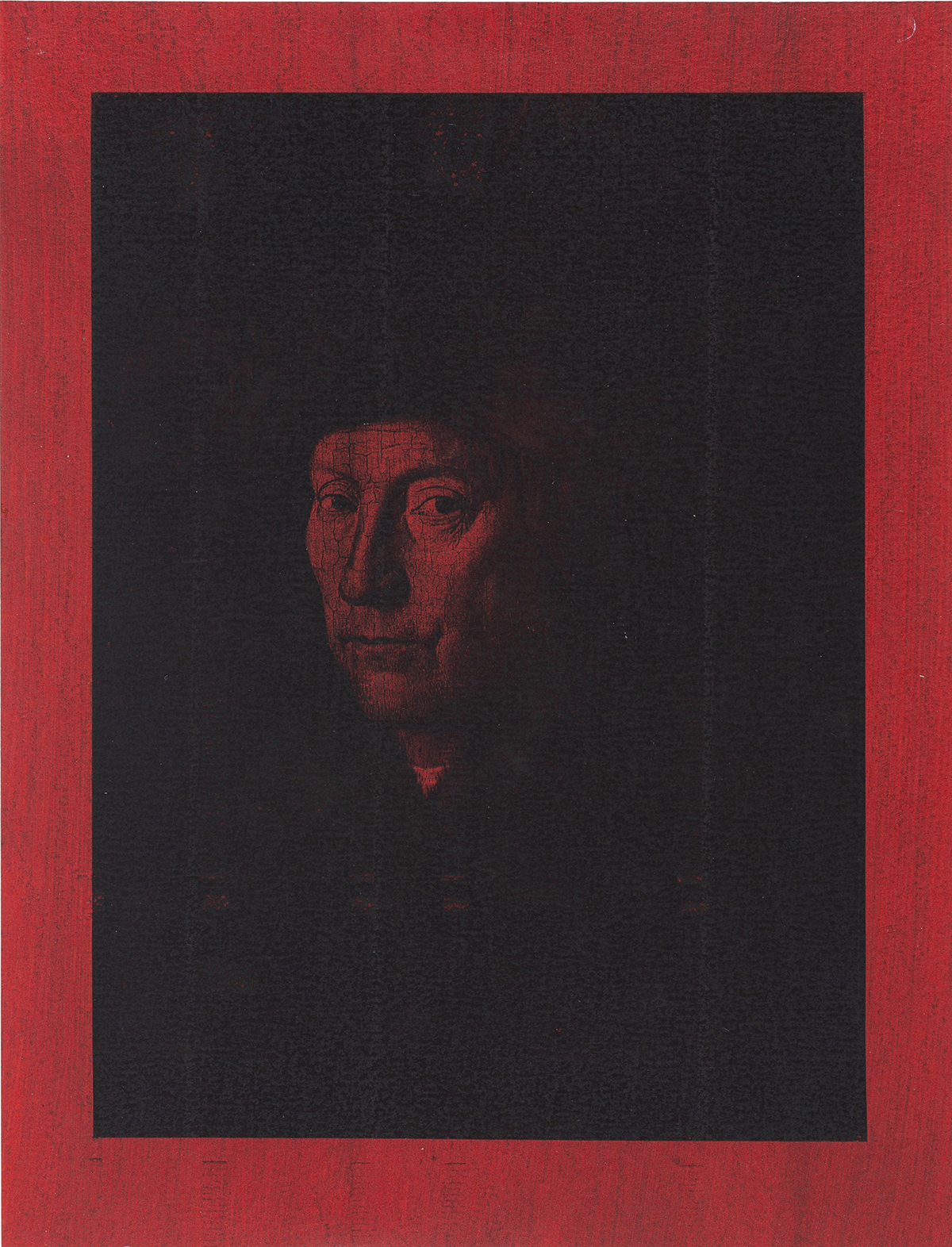

The installation was first shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1995. It marked a change in the artist’s line of inquiry, away from the photocopied works on paper that were the result of her early investigations into identity and towards the sprawling forms, often made from liquid bronze and steel, that speak to the shifting nature of the self, our connections with each other and the cosmos. Those early works focused around images sourced from art-history textbooks. The artist photocopied portraits by Rembrandt and van Eyck and Botticelli and then used carbon and paint to partially obscure the sitters’ faces. Untitled (After Jan van Eyck) (1985) and The Silence of Painters (1987) hint at this process of concealing and revealing, evoking both the artist’s cultural distance from the Western canon and the way the aura of the originals survives appropriation and repetition.

Courtesy the artist and Sullivan & Strumpf, Sydney & Singapore

At the time, these works were read as fashionably postmodern. But for Lee they were personal. “The copy is the story of me and so many others,” she says. “In the old days [of photocopying technology] carbon had to be fused onto the paper. I realised that the photocopies had their own kind of beauty. It was this recognition that I was such a bad copy of China. I was born in this country and just wanted to belong – but I could never.”

In No Up, No Down the walls of a white room are adorned with individual ‘flung ink’ paintings in shades of orange and indigo. In 1993 Lee travelled to Beijing on an Asialink fellowship, intending to study traditional Chinese calligraphy. She didn’t connect with it, instead making paintings by pouring and spilling ink. The technique, embraced by Ch’an Buddhists in China during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), saw monks meditate before throwing the liquid on paper. The marks they made, the consequence of chance rather than intention, were thought to reflect the true nature of the universe.

No Up, No Down channels the energy of an explosion. The work’s dramatic scale and deceptively simple presentation spark a sense of introspection and expansion in the viewer. Lee’s ability to distil opposing elements into a visual language is a hallmark of paintings like White Sacrament (1985), an appropriation of El Greco’s The Apostle St Andrew (1610–14). A white cross bisects an image of Saint Andrew, resembling a ghost trapped in canvas. The saint is rendered by the artist in encaustic, a combination of dark pigment and beeswax. The artist attempts to find herself in the grand narratives of Western religion but comes up lacking. The cross becoming a way to ‘cross out’, a sacred symbol turned visual disclaimer. Influenced by the ‘black paintings’ of Ad Reinhardt, a formative influence, it remains one of her more powerful early works.

In the Museum of Contemporary Art’s third-floor galleries a room is given over to a new commission, Moonlight Deities (2019–20), a series of paper panels suspended from the ceiling. Perforated with circles of different sizes, they resemble cratered surfaces. The work is still in progress, she explains. You walk through it, encountering the way the moon’s ghostly pallor can render an ordinary night ethereal. Lunar bodies have long symbolised the cycle of hours and days, and the work that references the Buddhist philosopher Dogen immerses the viewer in moving shadows. Here, the artist invokes temporality as fleeting and unknowable, even as it shapes our daily lives.

On a far wall hangs Under the Shadowless Tree (2020), a swathe of indigo blue striated with drippings of black beeswax, as radiant and inscrutable as the horizon. Wonder may not be fashionable. But it’s central to Lee’s project as an artist.

“The mind only knows what the mind knows, but if you [use] the entirety of who you are, the heart, the mind and the body together, there’s a totality you are thinking with,” she says. For Lee, trusting her intuition rather than relying exclusively on her intellect is about pushing beyond a version of selfhood rooted in binaries and categories. Her work owes its imaginative force to its willingness to move beyond the strictures of Enlightenment thinking, finding new visual modes to voice old ways of being. “It’s important that it’s beyond my reason,” she says.

Lee’s grandfather moved from China to Australia for work during the early 1900s. As he grew older, he gave up his place in the country to Phillip, Lee’s father. (During the White Australia policy, which was established in 1901, a nonwhite worker could bring a family member only if they gave up their own place and moved out of the country.) A sympathetic immigration officer allowed Phillip’s family to join him. His wife, Lily, who had been battling the rise of Communism in mainland China (where, to survive, she was trading gold on the black market), arrived with their two young sons in 1953.

Lee, born a year later, started drawing in childhood. “You are speaking with this accent and feel this yearning for recognition, for belonging, but it is just not there,” she says. “Drawing allowed me to figure out how I was connected to the world and how the world was connected to me.”

In 1975 she attended teachers’ college in Brisbane, before moving to London later in the decade to study at the Chelsea School of Art. “I was thrilled to be accepted [to the school], but I was struggling,” she says. “Australia was where I was born but it was also the place of my greatest discomfort, so I had to return to understand my psyche.”

On her return she worked on the photocopy works. But she found Zen Buddhism (which had been repressed in China during the Cultural Revolution) in 1993, after a period of study and meditation. Zen Buddhism gave the artist the gift of a new praxis, one that was less interested in the limited language of identity and more in the infinite mysteries of existence.

“In Zen, it isn’t ‘who are you’ but ‘what is it that exists in this moment,’” she explains. “This is such a different question.” Presented with this new way of thinking, Lee became interested in a vision of selfhood as unknowable as the universe, moving beyond her investigations into cultural identity. No Up, No Down spoke to this understanding of self as part of a constellation of cosmic forces. “[I’d] realised that the boundaries of self are not limited by the boundaries of your skin,” she says.

Then, during the early 2000s, the artist’s nephew was diagnosed with an incurable cancer. He died 18 months later. Lee made one of the most profound works of her career – an installation that featured 100 Chinese accordion books (a form that had originated during the Tang dynasty [618–907] in China, primarily for use in recording Buddhist scripture). In a way, the artist was also reconnecting with spiritual traditions that were threatened during the Cultural Revolution, to be reimagined and preserved beyond the country. The work, Birth and Death (2003), contains red-and-black portraits of her family reaching back five generations.

“I wanted to give Ben, posthumously, his place in the history of our family,” she says. “There are five images of each individual during different stages of their life, so [it shows] the passage of time.” It reflects universality and individuality, the interconnected nature of history, present and future.

Lee tells me that the gift of not belonging has helped her move towards artistic freedom. “I am never going to be Chinese and I’m never going to be white, am I?” says Lee, who is working towards a solo show at her Sydney gallery, Sullivan & Strumpf, in February. In May she will take part in a group exhibition at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art – she became a member of the space, which champions Asian-Australian artists, not long after it was founded in 1996. “But I have these affinities with strands of philosophy.”

Five years ago, Lee swapped her house in inner Sydney for the Byron Bay hinterland, home to starlit skies and subtropical rain- forest. Materiality has always mattered to Lee, but her recent work is elemental, an attempt to reach a point of transcendence. She makes works such as Seeds of a new moon (2019) by flinging molten bronze onto the floor of a foundry. The glimmering droplets symbolise pieces of the cosmos. They capture the paradox of sameness and difference, pointing to the patterns of the universe that we are part of despite our individual lives and identities. The Life of Stars (2018), which stands in the forecourt of the Art Gallery of South Australia, is a six-metre-tall sculpture that plays with the connection between interior and exterior realities. Its surface, pocked with holes that radiate pinpricks of light, recreates the galaxy in miniature.

“It invokes the breadth and depth of everything that has existed right now and exists in the future,” she says quietly. “None of us can exist except the other [also] exists. We are connected and that is the most important thing [to] understand.”

Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dew Drop is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, through 28 February Neha Kale is a writer and editor based in Sydney