It is only now, at eighty-six, that this pioneering artist is receiving her first retrospective

In September 1981 Lorraine O’Grady crashed the opening of Persona, a group exhibition at the New Museum featuring only white artists. Dressed as her alter ego, beauty pageant-winner Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (MBN, ‘Miss Black Middle-Class’), she wore an elaborate gown and cape fashioned from white gloves, a sash and crown, and carried ‘the whip-that-made-plantations-move’. Equally critical of Black artists and white art institutions, MBN gave out flowers and whipped herself before delivering a challenge to the crowd: “Now is the time for an invasion!” Four decades on, MBN’s rebuke continues to resonate, but it is only now, at eighty-six, that this pioneering artist is receiving her first retrospective.

Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, curated by the Brooklyn Museum’s Catherine Morris and critic Aruna D’Souza, brings together 12 major works spanning O’Grady’s career and introduces us to her latest avatar (featuring a suit of mediaeval armour topped by ‘headdresses emblematic of the Global South’) in Announcement of a New Persona (Performances to Come!) (2020). The exhibition title gestures towards the artist’s investment in destabilising binaries and her commitment to the diptych as her weapon of choice. Moreover, in challenging binary thinking, she simultaneously explodes the finality of her own work: as the titling and dating of many of the works implies, O’Grady is never completely satisfied with her own answers but instead frequently returns to her pieces to revise, reinterpret or make new critical interventions.

Throughout the exhibition, O’Grady’s treatment of the relationship between text and image, content and form, questions false dichotomies and hierarchies to produce a ‘visual literature’. The poems she ‘wrote’ in Cutting Out the New York Times (1977), formed of clippings from the paper’s Sunday edition, use text as image in diptych collages that are performed throughout the museum. Mounted at different angles, the cuttings move across the panels with humour, a series of juxtapositions that seek coherence, in contrast to the Surrealists’ chaos, but without succumbing to a need for closure. O’Grady returned to these collages in 2017, editing the 221 original panels down to 25 diptych haiku.

41 cm. Edition of 8 + 1 AP. © the artist/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York

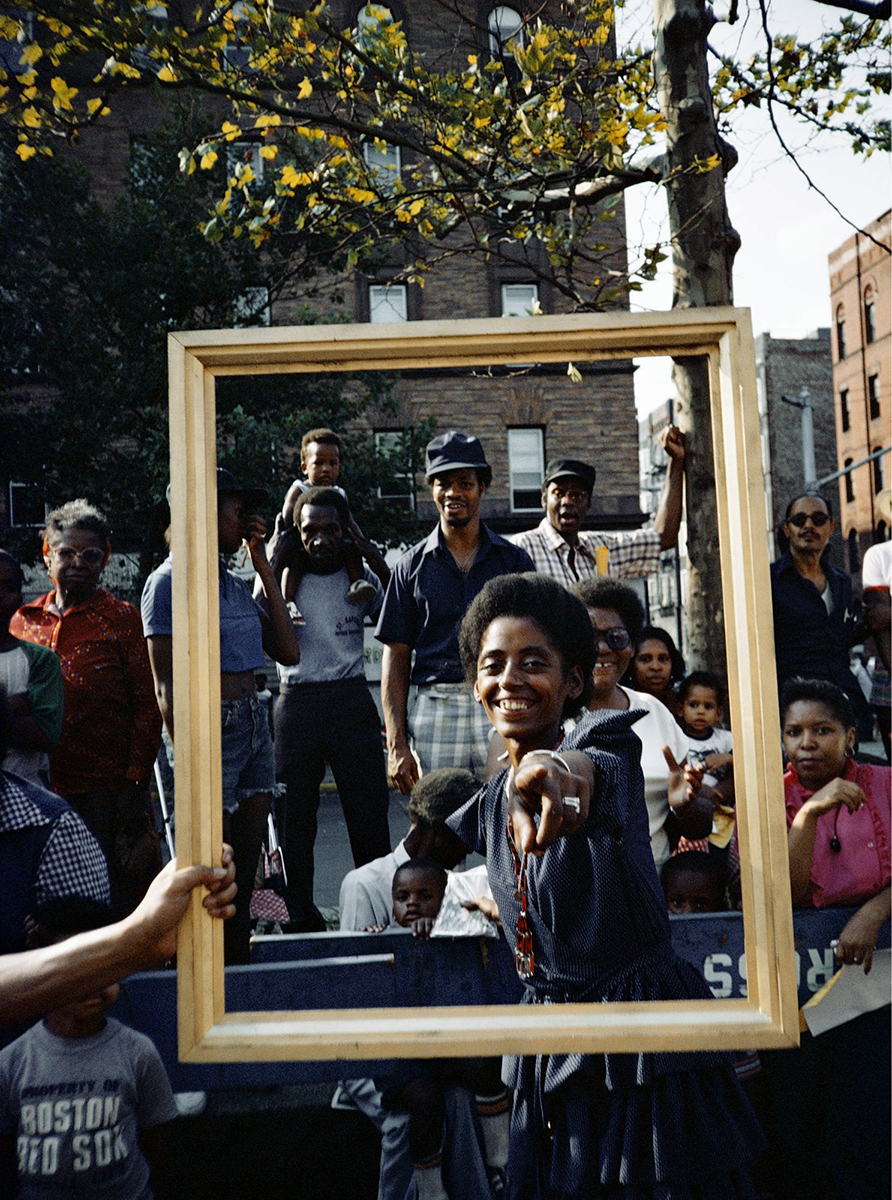

Another of O’Grady’s critiques of the artworld during the early 1980s was Rivers, First Draft, or The Woman in Red (1982/2015). Photographic documentation, framed with provocative captions, recreates the Central Park performance, a ‘collage in space’ in which the artist chronicles her personal, political and artistic journey. Characters identified only through their vibrant, colour-coded costumes chart O’Grady’s passage from Little Girl (in white dress with a pink sash) to the Teenager (in a magenta jumpsuit), to the mature and self-assured Woman in Red. The mythical/ dreamlike quality of the narrative is further dramatised through the obstacles the artist encounters and ultimately overcomes: the ‘Art Snobs’, the ‘Debauchees’, the ‘Black Male Artists’. Aloof but ever-present is the Woman in White, the maternal figure whose expectations O’Grady also rejects through her rebellious spraypainting of a white stove red.

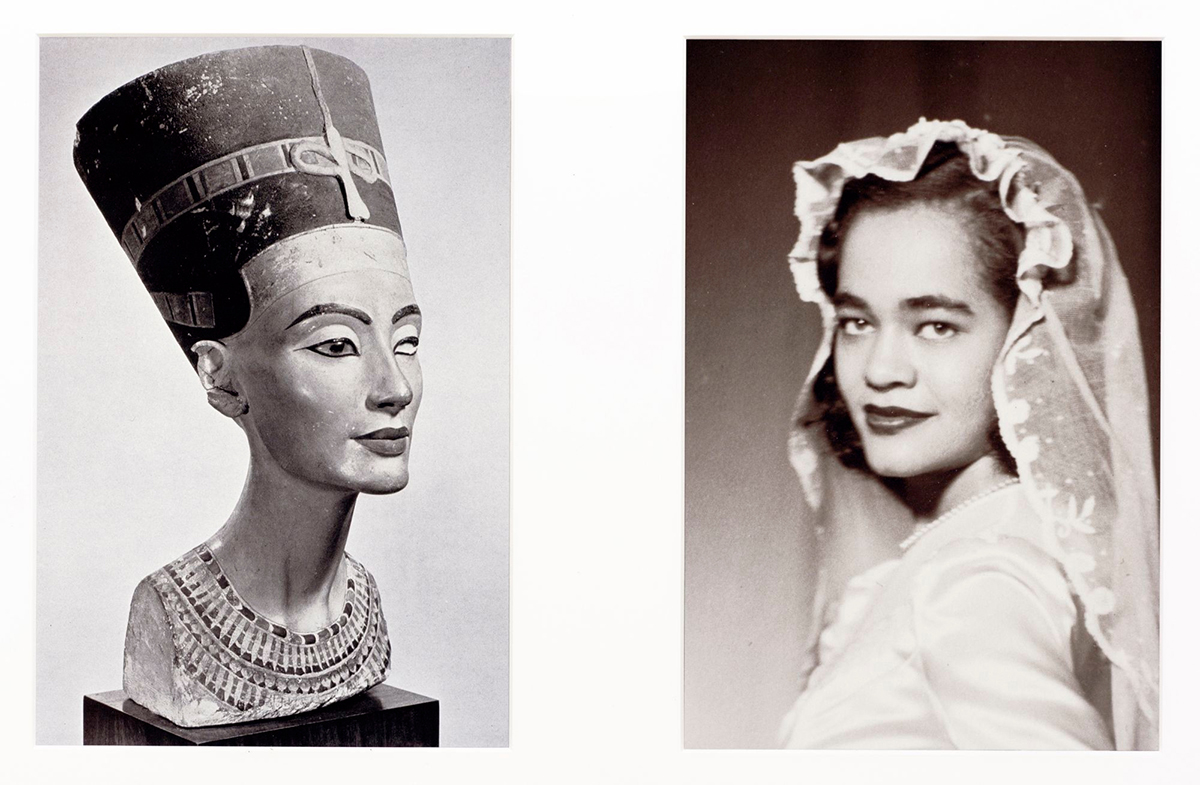

Both/And mostly occupies the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art but also spills out into the museum’s other floors, a curatorial gesture that echoes the inability to contain O’Grady within the confines of traditional ‘segregated’ spaces and the way in which her work is instinctively conversant with other parts of the art-historical narrative. While conceptually provoking, this strategy risks compromising the integrity of the exhibition through its dispersion. The interspersal of Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994) throughout the Ancient Egyptian collection is perhaps the most effective articulation of this strategy. The 16 photo-diptychs combine photographs of the artist’s late older sister, Devonia Evangeline, and her family alongside images of sculptures of Nefertiti and her ancestors. The series, which predates both academic and popular interest in the African origins of Pharaonic Egypt, creates a dialogue between O’Grady’s personal history and the narrative of Ancient Egypt produced through Western museological practices that have de-Africanised this heritage and rendered it European. While the diptychs contrast an intimate family album with stone sculptures intended to memorialise dead royalty, what is most striking about these works are the similarities that extend across centuries and continents.

Both/And presents an artist whose oeuvre remains both vibrant and timely. The energy and expanse of the work are undergirded

by a wealth of archival material. A testament to the artist’s diligent recordkeeping, this archive reflects O’Grady’s explicit awareness of the need, as a Black woman in the face of limited and limiting art institutions, to maintain a command over the (re)presentation of her work.

Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at Brooklyn Museum, New York, through 18 July

From the May 2021 issue of ArtReview