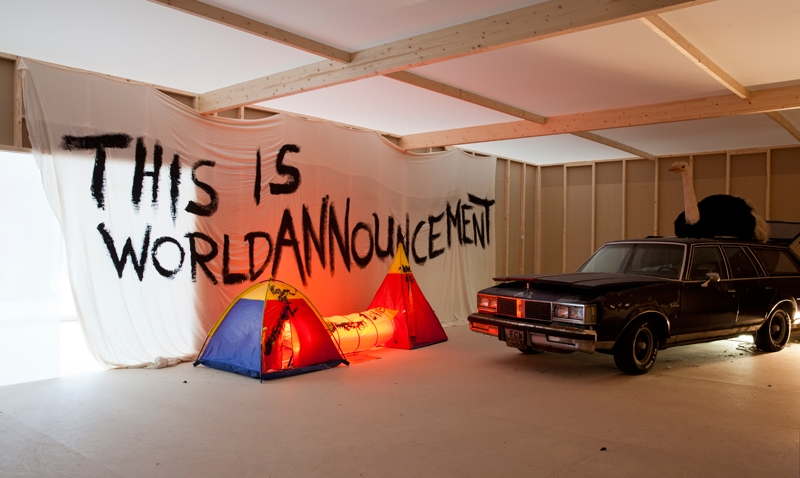

A dark wall made of raw wooden planks: the roughly sawn door has a peephole in it, as well as a hole for a dog; fish hang from drying racks; a cartoonish black-and-white wall drawing features a church, a warrior and an ostrich. The so-called Welcome Center in the late Christoph Schlingensief’s large-scale installation Animatograph – Icelandic Edition. Destroy Thingvellir (2005) gives a slightly menacing hint of what awaits inside the shedlike construction that houses the piece. On entering, one is instantly subjected to a sensory overdose. Projections, photographs, notes, objects and sounds fill the gloomy, labyrinthine corridors leading to the heart of the artwork, a revolving stage. Stepping up onto it, the viewer is suddenly a part of the show, doubling as both spectator and spectacle. Sitting on an old sofa, sharing the space with scattered props – a toilet, flags, signs, texts and drawings – you slowly move around the shifting scenarios, flooded by light from projected images and vibrating with loud announcements from wall-mounted loudspeakers.

Showing Schlingensief’s work in Malmö Konsthall – an airy, light-drenched icon of optimistic Nordic museum architecture from the 1970s – at this conflict-ridden moment in European history is undoubtedly a piece of good timing. Like Europe as a whole, Malmö, home to a relatively large immigrant population, is struggling with segregation, the rise of rightwing extremism and religious fundamentalism. Nevertheless, from my Stockholm institutional perspective, the local cultural institutions, such as the Moderna Museet Malmö and Malmö Konstmuseum, seem to have a growing consciousness of how culture has become a warzone and of the need to argue for culture in society at large. New Konsthall director Diana Baldon’s first exhibition here is clearly fuelled by this same ambition. In The Alien Within – A Living Laboratory of Western Society, the work of the main protagonist, Schlingensief, is accompanied by a programme of lectures and performances, including ones by urbanist Saskia Sassen and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha that seek to address culture’s role in times of social unrest.

The show is the first presentation of Schlingensief’s work in a Scandinavian art institution. Dense, thought-provoking and on the whole convincing, it struggles with the problem of how to exhibit the renowned and controversial director, filmmaker and activist’s oeuvre, which was originally made to be performed. The formula here is an archival approach, adding documentation from several performances and actions, such as the much-debated Ausländer raus – Bitte liebt Österreich (Foreigners Out – Please Love Austria) from 2000. The no-fuss documentary approach is effective; it also offers the added bonus of giving the Malmö audience an idea of Schlingensief’s method, and of actually seeing him at work, ironically incarnating the myth of the charismatic demon director, habitually with a megaphone in his hand, addressing the masses.

Animatograph, with its references to protocinematic visual technology as well as to the Wagnerian gesamtkunstwerk, was originally conceived as a portable device that would assume different shapes depending on the context. The version showed in Malmö, the only one of Schlingensief’s few installations to have remained intact, was commissioned by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna, for Reykjavík Arts Festival 2005. It takes us on a vertiginous and chaotic journey through the ancient sagas of the North, the songs of the Nibelungs, as well as Germany’s colonial past, and pays tribute to giants such as Joseph Beuys and Dieter Roth. As in all his works, Schlingensief brutally wrenches the elegant suit of European culture inside out, exposing its bloodstained lining, and linking it to the xenophobia, social injustice and exclusion of today. But perhaps even more vital in the context of the harsher climate for freedom of expression in our culture is Schlingensief’s uncompromising method of conflict and confrontation. This is an art that demands a space where it can act, without an obligation to be either instrumental or obedient.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.