The incendiary films of the late pioneer of African cinema do not merely critique power but discern the social, political and even metaphysical forces at work beneath the surface of the everyday

‘I am not going to justify myself in the eyes of American university scholars. But I would like for them [Westerners] to come to Mali so we can see together and discuss together, and so that they may touch reality with their own fingers,’ Souleymane Cissé once said to film scholar Nwachukwu Frank Ukadike in a 1997 interview. To see together, then touch reality anew, is what the best of education does – and that is who Cissé, in essence, was: a visual educator.

His death on Wednesday at a clinic in Bamako, Mali at the age of eighty-four was an unexpected tragedy. His teachings were not done: Cissé had been due to fly to Burkina Faso capital’s Ouagadougou the very next day to chair the jury at the 29th edition of FESPACO, the continent’s oldest film festival. Born in 1940 in Bamako under French colonial rule and raised a Muslim in a Bambara-speaking household, Cissé was a passionate cinephile from an early age, often going to the cinema unaccompanied (much to the dismay of his parents) after his brothers first took him to a movie theatre at the age of six. He attended secondary school in neighbouring Dakar, Senegal, and returned to Mali in 1960 after its independence.

Cissé’s interest in getting behind the camera was piqued by social and political injustice. After seeing a news film about the brutal assassination of Patrice Lumumba (the first president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) he knew he wanted to direct, but soon realised that, in his words, ‘making film in Africa belonged to the realm of a miracle.’ French colonialism had left behind a particular media landscape in Senegal, Mali, Mauritania and Côte d’Ivoire that that the Malian filmmaker and scholar Manthia Diawara called ‘technological paternalism’: Africans were welcome as ethnographic subjects and crew, but not as independent producers and directors. In 1963, the French Ministry of Cooperation created a Bureau du Cinéma that would provide funds to African filmmakers if they let the bureau have the final say over scripting and post-production. This was unrelated, however, to the pervasive film distribution system in Francophone West Africa (under the monopoly of private French companies) who would exclude African films from commercial screens, flooding the African market instead with B-grade French, Indian and American films.

Uninterested in ‘justifying himself’ to anyone but his own people from the off, Cissé opted for a free filmmaking education at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow (VGIK). The Soviet Union had cultural and training agreements signed from the late 1950s onwards with countries such as Guinea, Mali, Syria and Iraq, allowing hundreds of students to study there on grants. Cissé was taught there from 1963-9 by the celebrated Soviet filmmaker Mark Donskoi (as were his contemporaries, the ‘father of African cinema’ Ousmane Sembène, and Sarah Maldoror, one of the first Black women to shoot a film in Africa). Returning home in 1969 and doing a stint in directing newsreels and documentaries for the Malian Ministry of Information, he reimmersed himself in the issues facing Malians. When he finally set out in 1972 to make his first feature, he felt both admiration and frustration towards his training in socialist realism. The Soviet Union had taught him how to capture what he saw, but he believed it was Africa – with its oral and gestural storytelling forms, its spiritual wealth, its history, and its politically incendiary present – that should be teaching the world how to see.

Cissé’s feature-length narrative films, which he both directed and wrote, are unique in how they carry this responsibility without ever falling into didacticism. His films channel the anti-colonial thinker Frantz Fanon’s insistence in The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that the changing social, cultural and political currents within any given society should both ‘modify, and give precision’ to the work of a cultural creator from that society. At the same time, his films are each a world unto themselves, and unlike the work of any other African filmmaker.

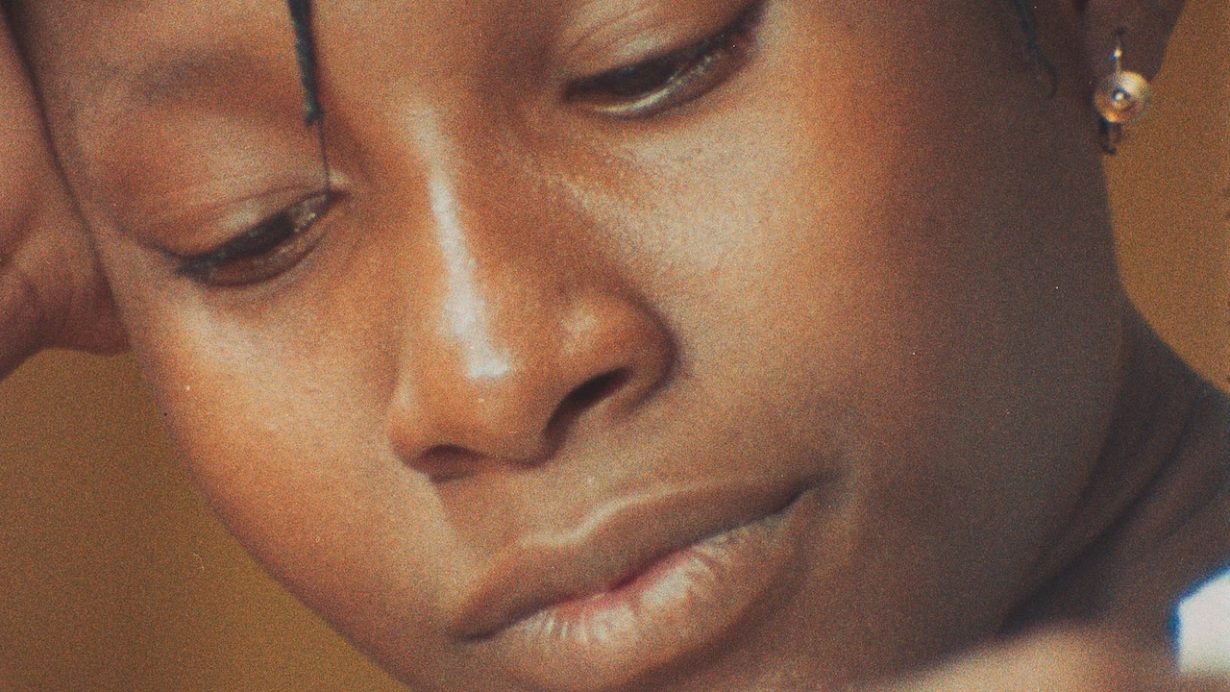

If Cissé’s films form a kind of visual pedagogy, Den Muso (1975) is his first narrative feature (or, as it were, textbook) on the intersecting oppressions of gender and class in postcolonial Mali. The title, which translates from the Bambara as ‘The Young Girl’, tells the story of a mute girl who is sexually assaulted and subsequently rejected by her family, becoming both a literal and symbolic embodiment of forced voicelessness. In the absence of spoken dialogue, Cissé composes meaning through the visual grammar of enclosure: framing his protagonist within tight interior spaces, shadowed corners and obstructed doorways that visually articulate her entrapment. The film’s banning by Malian authorities on the grounds that it was ‘socially destabilising’, and his subsequent stint in jail, marked Cissé from the off as a filmmaker whose camera would challenge silence.

His second feature Baara (1978) moves from the rural to the urban, widening his scope to interrogate the tensions between labour and capital in a rapidly stratifying postcolonial society. If Den Muso was about the unspeakability of trauma, Baara – Bambara for ‘Work’ – is about the cost of speech. Telling the story of a cotton factory manager who is killed by the factory owner for enabling a workers’ meeting, Cissé’s camera moves between two worlds: the dangerous machines where back-breaking, skilled work is done in collective rhythm, and the air-conditioned offices of the postcolonial elite who await their cuts as middle-men to French and American lenders. It is in these juxtapositions – between cotton and glass, movement and decay, collectivity and corruption – that Baara operates its critique. The film ends with a mass lay-off; Cissé does not offer heroic narratives of revolution. He invites the viewer to perceive the structural conditions that reveal Africa is now in a neocolonial bind; we are charged only to go forth with new eyes trained in drawing connections.

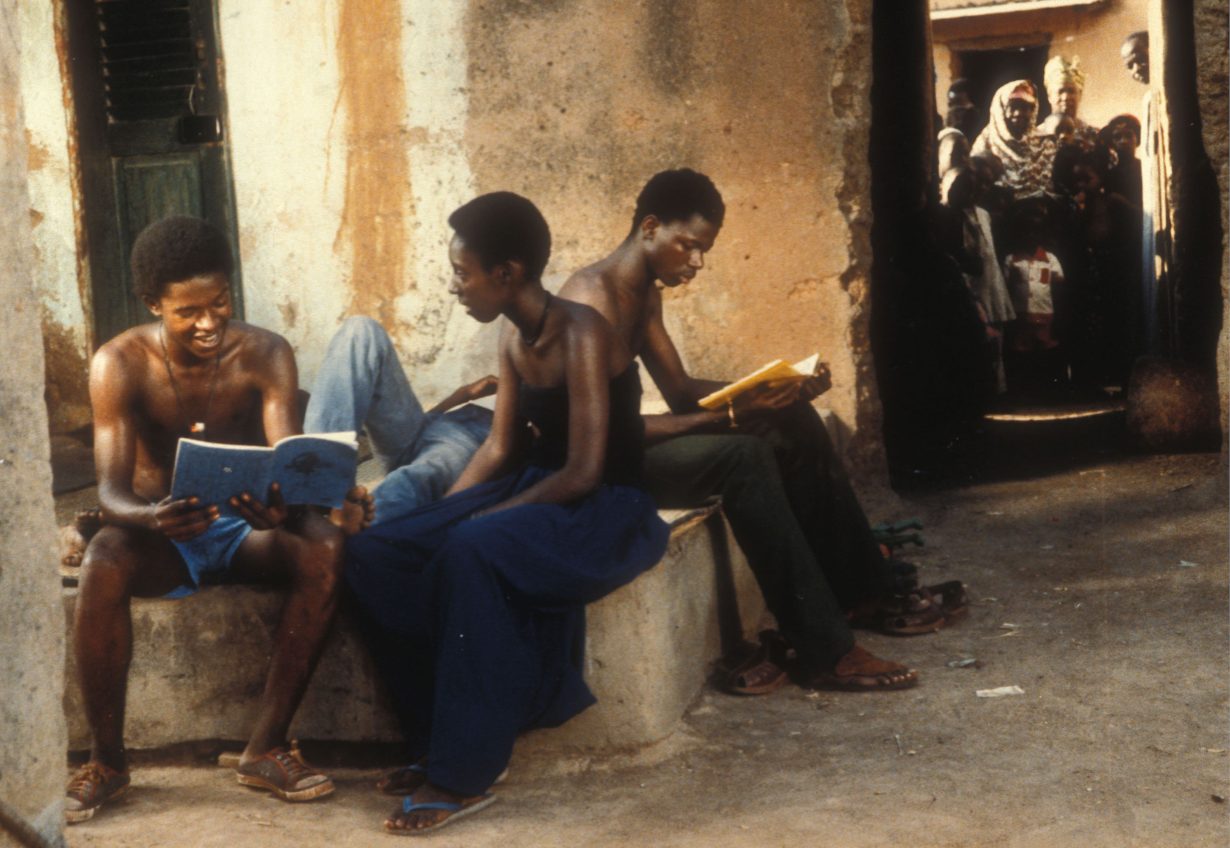

By Finye (1982) or ‘The Wind’, Cissés pedagogical concerns evolved from documenting the conditions of oppression to exploring the possibilities of resistance. Centred on two student lovers – Bah, the daughter of a Senegalese military governor, and Batrou, the grandson of a traditional Bambara chief – Finye weaves its metaphorical winds of resistance through the film’s visual and sonic textures. Resistance becomes encoded in unexpected places and forms, moving unpredictably: in one scene, just when we think this may be a generation-clash tale, the student activists find an unexpected ally in Bah’s grandfather, who calls upon ancestral powers to confront his grandson’s jailer. Moments of intimate defiance between students (shared glances, stolen moments of joy) become acts of quiet insurgency in prison. Finye helps us to see that knowledge, speech and political consciousness are not inert things granted by magnanimous institutions, but developed in situ by people struggling for them.

Yeelen (1987) moves further back to move forward: to the realm of West African myth and historical memory. Translating as ‘Brightness’ or ‘Light’, it is Cissé’s most philosophically layered film and is striking in its cinematography. Following the journey of Nianankoro, a young man who must confront his sorcerer father to claim his destiny, the film unfolds as an epic of initiation, where light (both literal and metaphorical) becomes the key to liberation. Cissé’s visual language here is more expansive than ever: vast Sahelian landscapes dominate life, while fire, water and earth serve as elemental motifs of transformation. But if Yeelen appears, at first, to be a break from Cissé’s explicitly political cinema, it is in fact an extension of this maxim – an exploration of how power is encoded not only in the institutions of the state but in cultural traditions, local epistemologies and the spiritual.

After the eighties, Cissé’s films continued to probe the entanglements of history, power and identity, though with novel dimensions. Waati (1995) or ‘Time’ expanded his vision beyond Mali, weaving a pan-African narrative that traversed South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire and Namibia to explore the lingering violence of colonialism and apartheid. After a long hiatus, Min Yé (2009) or ‘Tell Me Who You Are’ dissected the hypocrisies of Mali’s elite through a portrait of marital discord. These later works, while less overtly radical than Baara or Finye, remained unwavering in their commitment to cinema as a site of interrogation.

Cissé’s socially conscious cinema should be understood for its ability to enable sight. Even though his career has been award-studded – including the Carosse D’or, the lifetime achievement honour at Cannes – it is his work itself that honours him best. His films do not merely critique power; they train their audiences in discerning the social, political, economic and even metaphysical forces at work beneath the surface of the everyday. This, ultimately, is the pedagogical art of his cinema: not to tell, but to show – creatively, incisively and without compromise – and leave you with African tools of change.

Sarah Jilani is a lecturer in postcolonial literatures and world film at City, University of London