In the optical silence of lockdown, the filmmaker found a new freedom

Most of human history has been a lockdown. Across the millennia, the majority of people lived in a kind of bell jar. With the exception of the transcontinental explorers and colonizers, human lives were visually centripetal, directed inwards to villages, families, small communities or early cities. People didn’t see afar.

My own youth in Belfast in the 1970s was a version of this. In the Troubles we didn’t travel much, other people were a potential threat, few visited Northern Ireland and shops closed early. The Troubles were a lockdown. We stayed at home and thought outwards, centrifugally, seeing New York on TV and in films, and imagining being there.

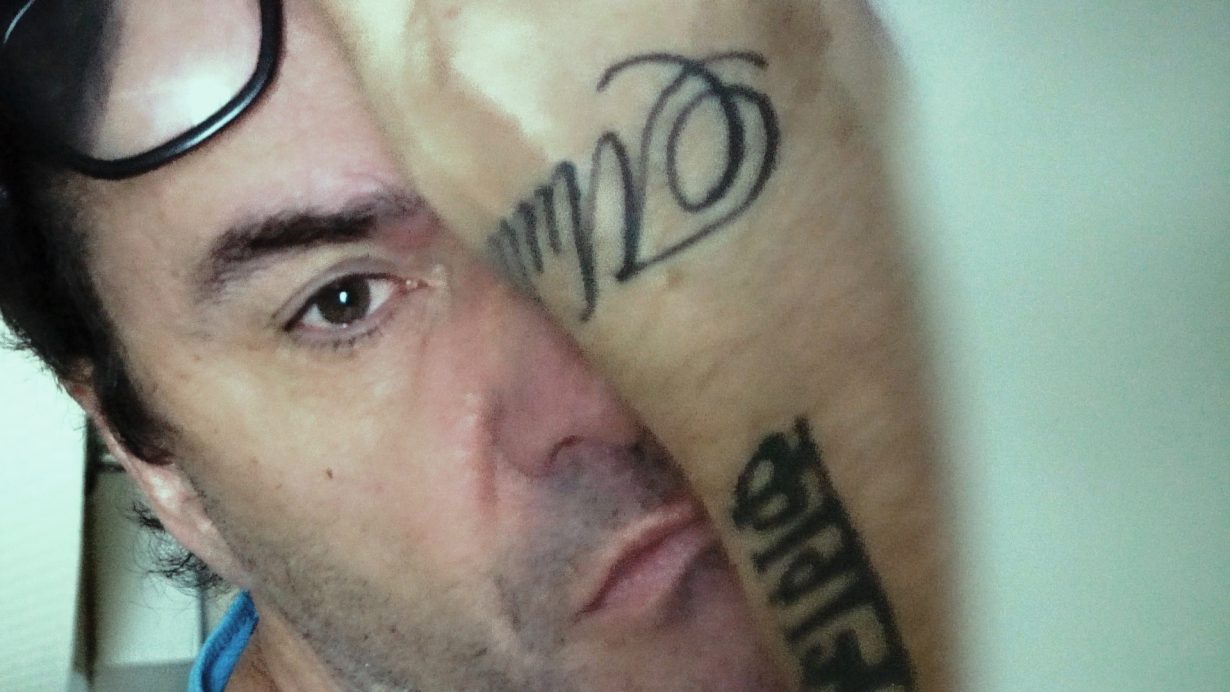

Maybe this is why I’ve made a film in a bell jar. I’ve adapted my book The Story of Looking (2017), which is a tour of the visual world, into a movie, but instead of jumping on planes to film the temples of India, the bazaars of Tehran, dawn in the north of Sweden or autumn at Frank Lloyd’s Wright’s Falling Water, I…stayed in bed. I didn’t even open the blinds in my bedroom. I love the films of Robert Bresson, whose central metaphor was imprisonment, but that’s not why I stayed put. And nor did COVID-19 force me to make a film about looking outwards by staying in. I decided to go nowhere before the pandemic imposed its bell jar from which we peeped, hibernating. Instead, my hunch was that, by doing the opposite of what is expected, I might trick myself into showing something more original.

As I filmed in my dark room, my bell jar, I felt as if I’d turned off the visual radio. There was an optical silence and, in that silence, I…projected. In Baghdad way back in the ninth century, scientist and polyglot medic Hunayn ibn Ishaq suggested that when we see, a kind of spirit travels forward from our brains, out through our eyes into the world, bounces off and is reshaped by an object, the new shape travelling back into the eye and, beyond, to our brain. This isn’t true, yet neuroscience now shows that when we look there’s more electrical activity from the back of our brain travelling forward than from the front, backwards. Looking isn’t gathering or absorbing from out to in as much as it is anticipating, searching through the previously seen.

The previously seen. In modern life, forced into the pandemic’s bell jar, we fed on the previously seen like a squirrel feeds on nuts that it has hidden away. As I lay in my bed I was aware of how much I’ve seen, and the feeling of recall. That feeling was consoling. I remembered looking out my window one dawn, months earlier, and seeing a guy standing on a distant rooftop, just looking at the cityscape. I remembered filming an old coal power station as its chimneys were blown up.

And in my self-imposed confinement, there was a further reduction of looking. I had recently got a diagnosis of a bad cataract and so went to an eye hospital to get it removed. Sedated, one eye covered, my eye was sliced into. Under the surgeon’s knife, I thought of a great Indian Bengali film, Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), in which the main character is mostly confined to a room and sees a chandelier reflected in his whisky glass. From this my inner eye jumped to kaleidoscopic Busby Berkeley dance routines and from that to electron microscope shots. I could not see – the lens in my left eye was removed – yet I projected so much.

What was the nature of this projection? The connection between the images I saw certainly wasn’t rational or inductive. Instead, my brain seemed to be linking together, as if in a chain, things with optical similarity – the microcosm of the glass, dance and microscope shot. Freed from the need to make sense, it played and soared like a swift in summer.

I wish it would do so more often. Russian theorist Viktor Shklovsky often wrote of what he called ostranenie, the de-familiarization of perception. He felt that we project too much, that when we see something we bring to it too many pre-seeings, that we are confined by what we have seen before. I love his idea of ostranenie. It aims for emancipation. Lying in my bed in the dark, and even in the pandemic’s bell jar, I admit that I felt a kind of emancipation. I haven’t been sick with COVID-19 (yet), so am very lucky. Instead, the bell jar was an incubator for me.

It gave me visual thinking time.

Mark Cousins, The Story of Looking, is released 17 September on Modern Films, in theatres and virtual cinema. ArtReview readers can watch the film here here.