Vivid canvases mask latent desires, writes Rodney LaTourelle

‘Restless’ is an adjective often used to characterise both Marsden Hartley and his work, due to his nomadic lifestyle and constant reinvention of his painting style in response to shifting influences and artistic ambitions. His complex succession of styles reflected his travels between America and Europe, uniquely combining the reductionism and subjective vision of Continental modernism with a mystic, constructive version of American regionalism. The ongoing sense of experimentation and discovery embedded in the American painter’s work is nevertheless anchored by a very distinct sensibility; a profound emotionality that set his work apart from his contemporaries. One of the largest retrospectives of Hartley ever mounted – over 110 paintings made between 1906 and 1943, the year he died, aged sixty-six – and the first in Europe since the early 1960s, the exhibition brings together the diverse range of Hartley’s canvases (plus drawing, writing and poetry). In a sequence of rooms corresponding to the artist’s travels and stylistic periods, the exhibition is divided chronologically into six ‘chapters’ that include research-style ‘pinup’ boards of related ephemera.

Hartley’s agitation might be accounted for by a loneliness and longing that engulfed his hardscrabble childhood, and as an adult he reportedly never lived for more than ten months in any one place; this restlessness is reflected in his artistic inquisitiveness but no doubt also relates to the difficulties of living as a gay man, in societies where homosexuality was illegal, even if accepted in the bohemian circles he moved in.

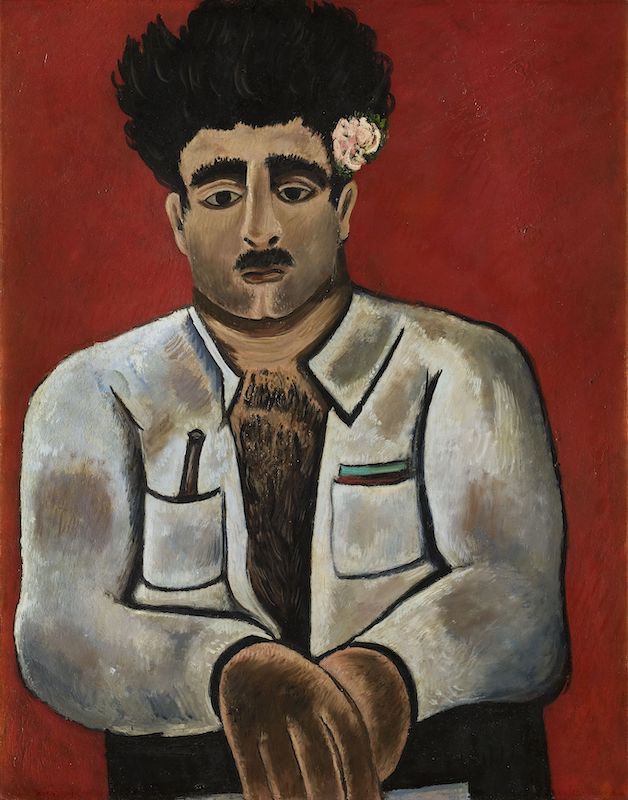

It’s through the coded subtexts of homosexual longing that the show proposes we understand the vision that informs Hartley’s heartbreaking paintings. The Louisiana retrospective repairs his neglect in Europe, while addressing Hartley’s latent homoeroticism (often misunderstood in his lifetime). In so doing it acknowledges the presence of gay desire obscured by the hetero-male modernist canon: the first work here is a Cézanne-style still life, Pears (1911), unmistakable phallic forms nestled together. The final gallery is filled with Hartley’s late-period, larger-than-life ‘hunky’ male figures (1935–43).

From the beginning, Hartley’s landscapes, abstracts and still lifes had a throbbing, vivid corporeality; he also often incorporated shapes reminiscent of body parts such as thighs, buttocks and especially phallic forms in his nonfigurative work. Yet soon after a tragic bereavement that marked a peaceful interlude in Nova Scotia, Hartley began to incorporate human figures. These are at once primitivist and sophisticated, often with a single figure against a monochrome background pressed urgently to the picture plane. His figures are surprisingly wooden, with strange proportions and geometric features that might be mistaken for outsider art for the virtuosic pathos Hartley achieves. His work shifts quotidian subjects into the symbolic dimension, yet here he approaches the mythic by evoking a ‘regressive’ sensibility in which visual liabilities are used as overtly emotional assets. Many works in this later style depict beefy, hirsute men, and were disingenuously described by Hartley as created for gymnasiums. Yet considering the homoerotic nature of this work – obvious from today’s perspective – Hartley is clearly, finally, ‘coming out’ here.

As curator Mathias Ussing Seeberg has noted: if Hartley painted the landscape like a figure for most of his career, in this final phase he paints the figure like a landscape. The bodies here are tenderly observed yet idealised, almost disembodied, epic and monumental. The resolute loneliness of the artist, perennially an unloved spectator and never a participant, assumes candid physical form. The result is a truly weird, beautiful, absolutely personal vision, establishing an unattainable longing that could be a metaphor for all the neglected dimensions eclipsed by modernism’s emphasis on heteronormative desire.

Marsden Hartley, The earth is all I know of wonder, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 19 September 2019 – 19 January 2020

From the April 2020 issue of ArtReview