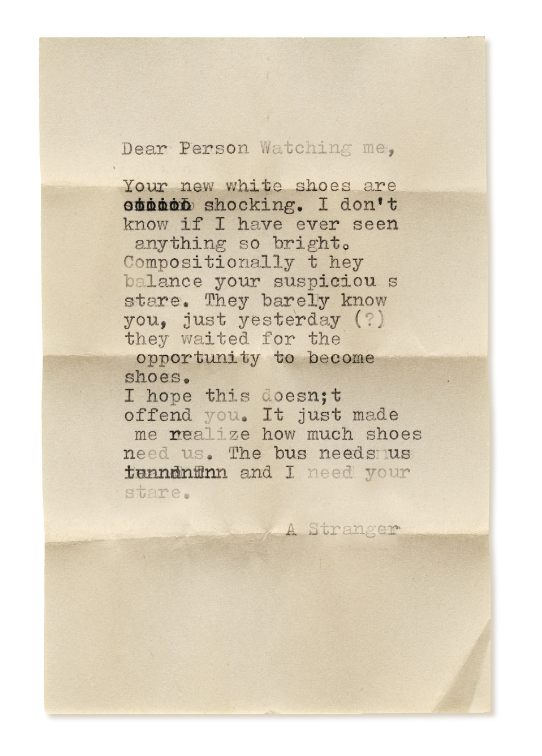

In 1990 Geoffrey Farmer started writing notes to strangers on public buses. In those days, in Vancouver, buses issued paper ‘transfers’, a time-limit punched into its thin newsprint, which enabled passengers to change buses and continue their journey. Farmer rode the bus with an old typewriter on his lap, rolled the transfers into its creaky frame and tried to write a tiny note-poem for a stranger before he or she alighted. One of them read, ‘I can see the dog you / are hiding in your bag. / I wish we were in Paris. / Thank You, / A Stranger’. The slumber of the daily commute was ruptured by a random act of empathetic weirdness.

Notes for Strangers, created while the artist was a student at Emily Carr College of Art & Design, heralded a set of ideas that Farmer has been working on for almost 30 years: ephemerality, chance encounters, connections across space and time, a desire to communicate. Yet, less than a year later, his worldview was changed completely: between 1990 and 1991 Farmer attended the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). The models he’d encountered at art school in Vancouver, where detached intellection was prized above all else, were exposed as a particular, limited way to be an artist, rather than the only way. When I talked to Farmer about his plans for the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, it was not the pavilion or even the work that first came to his mind, but a series of vivid recollections of that transformative year.

In San Francisco, he heard Kathy Acker read, in a manner that he’d never heard anyone read, Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914). He saw John Cage perform in January 1991, a performance that was mostly silence punctuated by guttural noises; while he initially thought the performance was ridiculous, when Cage discussed it afterwards, his eloquence and openness changed Farmer’s mind. He discovered William S. Burroughs’s ‘cut up’ method. Tony Oursler taught a class; Allan Kaprow and Carolee Schneemann showed up. Amidst the aids crisis, he became immersed in queer culture and history. He came out. He learned about the Venice Biennale, via a 1970 Artscanada magazine with a cover story on Michael Snow, Canada’s representative at the Biennale that year. He heard Allen Ginsberg read, and watched astonished as the poet shifted from calm, discursive lecturer to rhapsodic bard. What I understood listening to Farmer discuss his experiences was that he came to understand that while you could be an artist of considerable intellect, that didn’t mean you had to be dry. Intuition, language, emotion, performance, perhaps a hint of madness: that year in San Francisco gave him the permission to become himself – by becoming someone else.

He came to understand that while you could be an artist of considerable intellect, that didn’t mean you had to be dry.

Farmer took the title for his pavilion, A way out of the mirror, from the Ginsberg poem ‘Laughing Gas’ (written in 1958, published in Kaddish and Other Poems, 1961): ‘A way out of the mirror / was found by the image / that realized its existence / was only… / a stranger completely like myself ’. Why Ginsberg? In part because of his memory of hearing him read in San Francisco, but the reference to the poet – and the 1958 date – are part of a larger network of connections and coincidences enacted in April 2016, just as he started thinking about ideas for the pavilion.

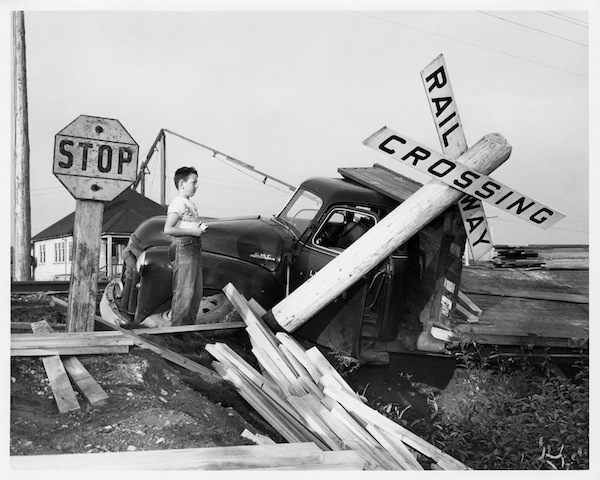

Farmer’s sister emailed him two black-and-white press photographs, dated 1955, that she had found in the basement of their father’s house. Both depict the aftermath of the same accident: a pickup truck slammed against a railway-crossing sign, pushed there by a train, its cargo of timber spilled out across a bank of earth like the buckling floes in Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice (1823–4). In one of the photos, a train zips by behind the crash, getting on with the business of transporting goods. In the other, from a slightly different angle, a dumbstruck kid – anonymous, placed there by the photographer – looks blankly at the scene, a half- eaten apple in his hand. There might have been no particular reason to pay much attention to the pictures – despite the voyeuristic melodrama of any accident, they are from bygone era, seemingly irrelevant. But it turns out that they had a profound personal connection to the artist: Farmer’s paternal grandfather was behind the wheel of the truck. And though he walked away from the wreckage, he died a couple of months later from a heart attack. Farmer had never heard the story before, only the faint susurrations of past family trauma from his emotionally clenched father, a man prone to violent outbursts. The potent images had been languishing for decades, their story all boxed up.

For an artist whose raw material is found imagery, these long-dormant photographs were a boon. The press photographs became for Farmer what he calls a ‘spring’: the point of departure from which flowed a range of inchoate thoughts and feelings, both personal and political. A nexus of coincidences started to bubble up the more he meditated on the images, and he wanted to incarnate all those immaterial leaps between events and ideas into a new physical structure. Ginsberg was the first of many connections Farmer started to make: when the email arrived from his sister, he happened to be reading Ginsberg’s Howl, which was written in 1955, the year of the accident. Turns out, in 1955, the students at SFAI had organised a reading of the poem. And this was also about the time that the Canadian Pavilion in the Giardini, a small hut of brick and angled glass, was being proposed (and eventually built in 1958, the year Ginsberg wrote ‘Laughing Gas’). One of the founding members of its architects, Milanese firm BBPR, had died in Mauthausen concentration camp, and one of the practice’s first postwar projects was a memorial – a gridded, geometric cube, with some similarities to the Canadian Pavilion – to the victims of German concentration camps. The Canadian Pavilion formed, moreover, part of the war reparations from Italy to Canada. The Giardini itself was born of war, with Napoleon razing a neighbourhood and rearranging the city at the end of the eighteenth century, the Canadian Pavilion atop a hill constructed from rubble, a residue of the Frenchman’s brute violence. In the process of developing all of these connections, Farmer read Kaja Silverman’s The Miracle of Analogy (2014); her ideas about found images, and the way in which photographs allow ‘us to see that each of us is a node in a vast constellation of analogies’, echoed many of his own thoughts about found photography and this project in particular. (Think of the immeasurable networks of found photographs the artist used in installations such as The Last Two Million Years, 2007, or The Surgeon and the Photographer, 2009–13.) Farmer had thus discovered the source of his ideas for the pavilion in a couple of old press photographs, at once anonymous and yet intimately connected to the very formation of his existence and identity.

Unknown Photographer (Collision), 1955, archival photographs. Courtesy the artist

Farmer decided he wanted to create a public space that incorporated references to Ginsberg, San Francisco, architecture, poetry, transparency, protest and the history of his family.

It was the question of how to give these ‘vast constellations’ concrete form that drove Farmer’s imagination. Farmer decided he wanted to create a public space that incorporated references to Ginsberg, San Francisco, architecture, poetry, transparency, protest and the history of his family. While he was at SFAI, he spent a lot of time at the fountain, a small octagonal structure with Moorish tiles. He thought of Ginsberg in Greenwich Village, and the fountain in Washington Square. He thought of his husband, who’s from NYC, and his memories of that fountain, and again of Ginsberg, who, like him, had to leave his hometown to forge his identity anew. The fountains became metaphors for origin myths, oases of communal learning, pleasure and healing. He decided to combine the external shape of the San Francisco fountain with the high-shooting water feature from Washington Square, creating a hybrid water feature that, conceptually at least, spanned a continent. With the history of the pavilion’s architects in mind, and their antifascist desire for openness and transparency, the artist will open up the pavilion to the Giardini, converting a cramped exhibition space into a public piazza. Thus the pavilion, and the hybrid fountain Farmer will create for the site, grew into a fusion of structures, a uniting of polarities, a memorial to a buried past and a spring of enlightenment.

But how could Farmer integrate the content of the photographs, the story of his family? Farmer knew that the planks of lumber that spilled from the truck were important. He decided to remake them, all 71, and incorporate them into the fountain. He cast facsimile planks in bronze, applied a print pattern and a patina to mimic wood, perforated them and devised a program to regulate the flow of water through the hollow bronze; he also punched holes in the ends of the planks so that water would spurt playfully from the ends of their hard, geometric edges. His recreation of these long-forgotten strips of timber echoes the nature of the whole project: Farmer starts with an accident, and transforms the residue into a playful, flowing dance. Another feature of the fountain will be a grandfather clock, an axe in its back, and from this structure the main jet of water will shoot 13 metres into the sky, matching the height of the Washington Square fountain. There is yet another element: a human-mantis figure, lifesize and cast in rough bronze, hunched like some sci-fi monster imagined by Giacometti, will sit in the centre of the fountain, a huge book on its lap, a pair of scissors jutting from its back.

Is it a figure of the artist? In the course of thinking about Farmer’s work, even before I’d heard anything about the pavilion, a line from William Blake’s ‘Proverbs of Hell’ (1790–93) kept coming to mind: ‘The cut worm forgives the plow’. I had an image of the artist as one of those farmers (no pun here – just another coincidence) who, one day in the field, hits a cluster of ancient artefacts with his plow, then spends a life-time interpreting the objects. The photo- graphs of the accident are just such objets trouvés: unearthed by accident, portentous and strange, sending the discoverer on a hermeneutic quest. For Farmer, the press photographs allowed him to talk to his father about his grandfather, unlocking an episode of his family’s history that was almost lost forever. His grandfather was a labourer, and both he and Farmer’s father endured the tribulations of midcentury life in the raw landscape and economy of Vancouver in its rough becoming. These stories of suffering allowed the artist to empathise with his father, come to some comprehension of his rage and gruff aggression. The past is a plow that leaves its mark unintentionally, just getting on with its daily tasks. A train is an almighty force. A violent father an inescapable presence. A life smashed, dug up, reformed; a pavilion cut open. A fountain placed at its core, a source of life, a site of synthesis and gratitude. The cut worm forgives the plow.

Geoffrey Farmer’s presentation for the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, A way out of the mirror, is on view through 26 November.

From the May 2017 issue of ArtReview