The American sees her work as founded on a mix of art, architecture and the creation of memorials, all of which she uses to honour the past and reshape the future

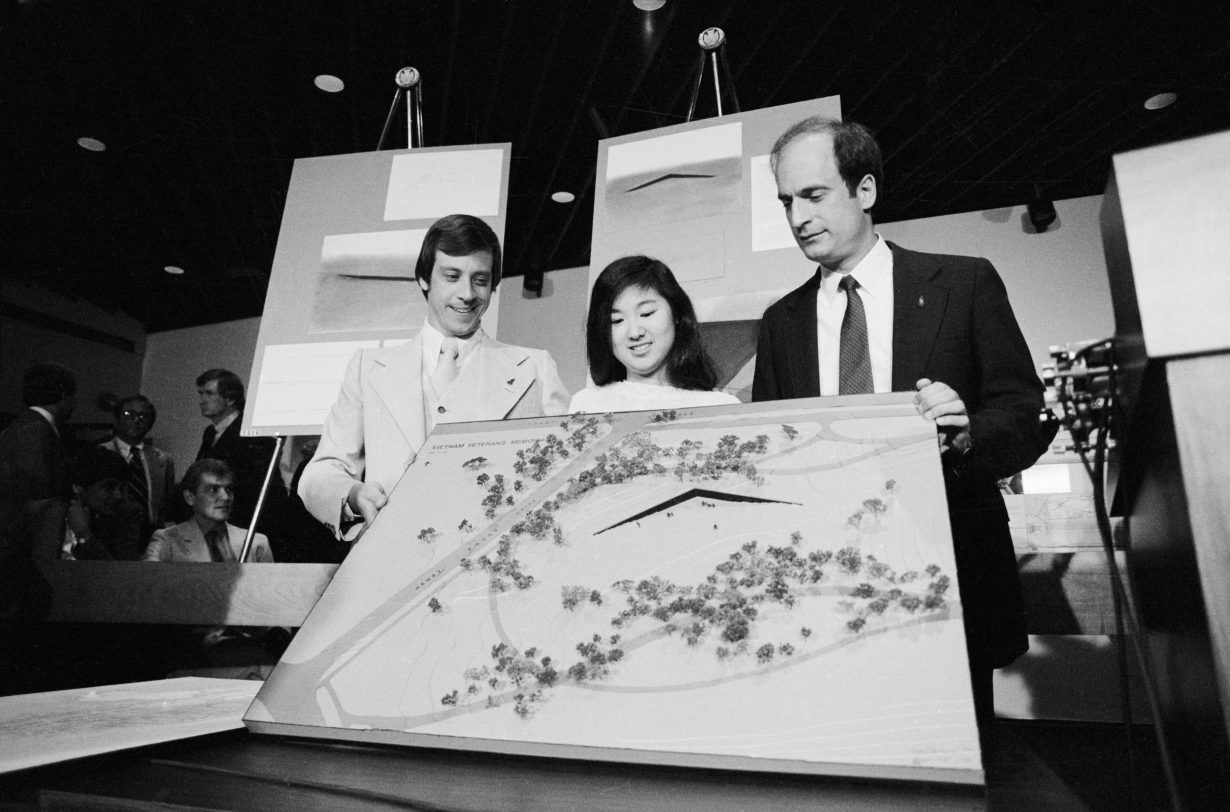

Could it happen today, in the political climate of 2023 America? As the famous story goes, in 1981, a twenty-one-year-old undergraduate submits a highly unconventional proposal for a Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, and in a blind competition against more than 1,400 other entries, she wins. Maya Lin, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, faces fervent opposition to her spare design – two long walls gliding into the land, bearing the names of the American dead – but in 1982 it is installed on the National Mall, and it makes her a star.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial has become one of the great sacred spaces in the United States. Walking down its path, people grow quiet. They use crayons and pencils to rub names onto paper. They leave flowers and other items. They linger. It is not universally adored, but it is beloved. When the American Institute of Architects published a survey of ‘America’s Favorite Architecture’ in 2007, it came in at number ten. It was the only entry in the top ten to have been built in the past half-century, and even more importantly, it was the only selection that could be classified as an example of minimalism, and an unusual strain of minimalism at that. This is an unspectacular monument – beneath the ground but exposed to light, mournful but not sepulchral. It invites collective grieving.

If the process were to be repeated now, it is hard to be confident that Lin would be able to see her commission through to construction. She faced racist attacks at the time, and had to defend her plan before Congress, but public discourse in the US has curdled a great deal since then. It is easy to picture Fox News host Tucker Carlson oozing condescension and indignation, and Republican officeholders rushing to line up behind him.

In the intervening 40 years, Lin has of course kept working. Now sixty-three and based in New York, she has carved out for herself something of a sui generis position in the US cultural landscape by moving between different but related roles, uniting different disciplines. She sees her work “as a tripod”, she said during a talk in February at Hongik University in Seoul, the three legs being art, architecture and memorials (or “memory works”, as she has also termed them).

What holds those legs together? Classic Lin pieces evince a quiet reverence for the natural world and an awareness of deep history. They tend to be restrained – her art often involves only a single material – and rooted in a functional logic, while exuding a beauty that is tinged by melancholy.

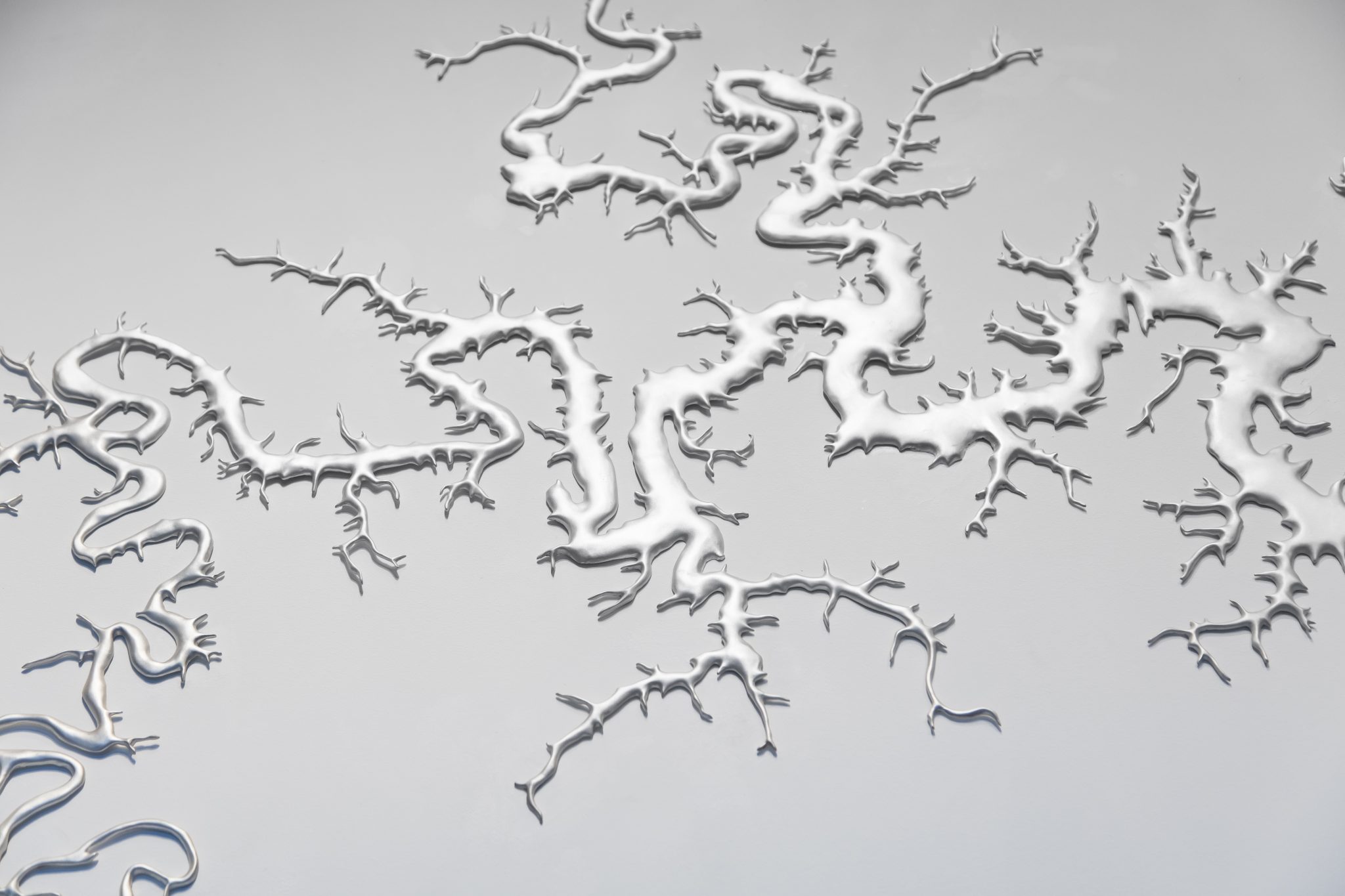

In a solo exhibition at Pace gallery in the South Korean capital that ran into March, Lin presented a few works that map rivers, a recurring practice for her. Thousands of tiny steel pins dotted a roughly 3-by-2m expanse of wall, meticulously charting Korea’s Imjin and Han rivers and their many tributaries (Pin Gang – Imjin and Han, 2022). It suggested a closeup of veins and capillaries, a frozen burst of lightning or even a faraway galaxy. On another wall, thin branches of recycled silver showed the flow of the Tigris and Euphrates, a similar spread of craggy lines (Silver Tigris & Euphrates Watershed, 2022).

Those waterways cross fraught political boundaries, which are absent in Lin’s works, and they have developed on a timescale beyond human memory. In her borderless models, Lin nudges viewers to step back and marvel at natural systems that operate across hundreds and hundreds of miles. There is a utopian tone to this exercise – the all-seeing cartographer’s belief that vast expanses can be mapped, and thus grasped in some way – but a certain fragility or even ephemerality defines much of her art. Pull those pins, and the map disappears.

Death haunted Lin’s Ghost Forest installation in Manhattan’s Madison Square Park in 2021. It involved installing 49 Atlantic white cedar trees that had been killed by climate change-induced saltwater inundation (in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey) upright in the green space. This ecological cemetery stood for six months, slowly wasting away as the season changed. It was not exactly a subtle endeavour, but it was certainly less heavy-handed than Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch (2014) project, which carted massive hunks of glacial ice into public spaces and let them melt.

Ghost Forest continues Lin’s enduring interest in making visible things that are kept out of sight, whether by geological forces or sociopolitical ones. Her Above and Below (2007), an undulating, skeletal web of epoxy-coated aluminium, is a three-dimensional map of the river system that sprawls beneath Indiana. (It hangs above a covered terrace at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which makes encounters with it all the more unreal: who knew that was buried below?) Her Civil Rights Memorial (1989) at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama, is a stone table that bears water (via a barely perceptible fountain) and text with a compact history of the movement. The Women’s Table (1993) at Yale University is another large flat stone and fountain, incised with spiralling numbers that count the women enrolled at the New Haven, Connecticut, school over its history. It begins with a long string of zeroes.

In recent years, Lin has been developing what she terms her ‘fifth and last memorial’, a multifaceted project that addresses the ongoing rapid loss of biodiversity, titled What Is Missing? (2009–ongoing). At its core is a website that maps the ecological history of the planet – discussing the living things and ecosystems that once thrived (cod as big as an adult human, just a century ago!) and what has been done to restore the environment. It also allows anyone to submit a memory about the environment. One anonymous contributor fondly recalls childhood visits to a Florida beach during the early 2000s, only to return recently and find ‘trash and debris that was littered along the sand, and floating in the water. It really broke my heart.’

As with so much of Lin’s work, her digital platform attempts to record and preserve the past with the ultimate aim of fomenting action, or at least a change in mindset. “How can we protect something if we don’t even know it’s missing?” as she put it in her Hongik talk.

That sensibility – attuned to the environment, eager to learn from the past – can be seen guiding Lin’s 2021 redesign of the library at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, with its emphasis on removing elements of previous renovations. Two cumbersome wings were replaced with smaller light-filled ones, with the intention of allowing its Frederick Law Olmsted-designed campus to breathe once more. Capacious windows were installed to facilitate birdwatching, and cramped spaces created by those prior construction jobs were opened up. Razor-focused on making an energy-efficient design, she picked materials long utilised for Smith buildings, like local stone, glass and timber.

Lin’s very way of working could be seen as embodying a distant era, before the rise of starchitects and supersized firms with offices around the world. She takes only one architectural project at a time, and her entire studio team never exceeds five people. (Architect William Bialosky collaborates with her on her building projects.) When tapped for a job, she will design “everything, including the doorknobs”, Lin said in her lecture.

A case against Lin’s approach to art and architecture could be that it is too literal, illustrating important issues or concepts rather than responding to them. Her land works have certainly felt one-note to me. Earth sculpted to resemble wave patterns or sinuous lines can seem impressive but a little dull, a technical designer’s idea of art. But much of her other work exudes an enlivening restraint, a rare concision that is born of careful research and a desire to make no unnecessary gestures. It is conservative, but only of a very specific sense.

Lin, I think, can be connected to what the American political scientist Robert J. Lacey has termed ‘pragmatic conservatism’, which he associates with mainstream liberalism (and the Democratic party) in the US – a Burkean-derived worldview that finds value in tradition but that embraces incremental reform, led by elites. President Barack Obama, who awarded Lin the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016, could be seen as an exemplar of that position. She wants Olmsted’s design to thrive, she wants history to be remembered with dignity and she will insert her work into the world only to the degree that it will have some kind of concrete benefit, whether practical or poetic.

So much of what gets built in the public sphere in the US now is awful and overblown: Michael Arad’s portentous 9/11 Memorial at Ground Zero, Friedrich St. Florian’s imperialistic World War II Memorial in Washington, or Vessel, Thomas Heatherwick’s baleful hypercapitalist fantasia (and, sadly, suicide device) at Hudson Yards in New York. Lin embodies a very different position. The subtlety that is the hallmark of her projects suggests, to me, a deep trust in an informed public. Her creations encourage moral and ethical thinking, but they do not hector, and they call no one to arms. Here are some rivers, they say, and here are some names, and here are some things that have taken place. How should we act now? What are we going to do next?