Amid the annihilation, Nikita Kadan explores a paradoxical freedom in Kyiv

The opportunity for Ukrainian Nikita Kadan to show at Kyiv’s National Art Museum is one of the more obscure consequences of the 2022 fullscale invasion of his country. His exhibition, Siren Sickle Satellite, is installed across the galleries in which the institution’s permanent collection should be; the historic paintings and sculptures, meanwhile, are stowed in a secret location far from the capital and Russian bombs. While this might be of great sadness for those wanting to gain glimpses into Ukraine’s history, it’s the perfect foil for Kadan’s work on museums and memory, which ranges from soundworks to charcoal drawings, the latter invariably depicting historic artworks and artefacts.

Still, what with the upcoming show and the ongoing war, the last thing I thought we’d be talking about, as I sat with Kadan in a hipster café in central Kyiv, was the tiny Japanese island of Ōshima. Lying in the Seto Inland Sea, it has been home to Ōshima Seishōen Sanatorium, a leprosarium, since 1909; some 30 people remain at the facility today, though their forced incarceration ended two decades ago. The subject came up when I asked Kadan what his next projects might be. It’s the kind of softball question often posed to wrap up an interview. But in this case it spun it off in a different direction entirely.

“I’m making a memorial to the residents of Ōshima,” Kadan said. “I’m using objects from the museum they founded.” Startled, I told him I’d just finished writing a book on leprosy; that we must be two of the rare outsiders to have been granted permission to enter the sanatorium and meet remaining former patients and patient-activists, all now in their eighties and nineties.

We will get to Japan and its dark history of eugenics, nationalism and cultural erasure shortly, but Kadan’s work, a commission from the Setouchi Triennale, makes sense: for over a decade the artist has been concerned with the stories that we collectively attempt to preserve, and with those that are forgotten or hidden. It is precisely these themes that echo through the biopolitical history of leprosy in Japan and, of course, feel acute to the artist’s situation at home in the wake of the Russian invasion.

For now, however, Kadan and I are with our coffees, our phones laid out on the table, the volume bar of my air-raid app turned up to its loudest. For Kadan, Russian aggression has been a lived reality for some time, an omnipotent trauma; for me, visiting Ukraine briefly, it’s all new. “I’m interested in the notion of history and art history, and the idea of a museum,” he says. “But I live and work in a country where museums are closed or empty because of the ongoing war, and where a number of museums and cultural institutions have been destroyed or looted. So there is a contradiction between my interests and my reality that I want to explore.”

Kadan’s primary interest – the question of how we construct our identity, both collectively and individually – is a universal one, and for him museums are totemic examples of that construction process. The artist has been appropriating institutional artefacts for over a decade, casting museums not just as repositories or places of education, but as mythological entities capable of both embodying and offering alternatives to the psychic understanding of ourselves and society. The context of the show, Kadan says, “is an opportunity to see how much art history is influenced by the history of wars and forms of mass violence”.

“I cannot unsee it in any Western museum, any museum in the world even,” he continues. “Violence seems to always underpin these highest examples of human achievement, of human spirit. Every museum has its own history, which is the history of modern nation-states, the history of empires, nations and nationalisms.”

Where the National Art Museum has previously provided a chronological path through figuration and abstraction, classical busts and portraiture, Kadan will install Tryvoha (The Sirens and the Mast) (2023), a sound installation for which he commissioned an opera singer to imitate the wail of air raid sirens. Tryvoha is Ukrainian for ‘air raid alarm’ and ‘anxiety’. “By being sung, the air raid siren becomes the Siren of Greek myths,” Kadan says. “Combining opera and this alarm, I wanted to say something about highbrow culture and the reality of wartime survival.” It is an eerie work, the speaker installed in a semicircular white curtain, which feels both like a stage and a medical screen: the overriding tone is of the uncanny.

The bulk of the show foregrounds Kadan’s gothic, dour charcoal drawings. At the Place of an Absent (2025) includes a pair of floor-to-ceiling banners installed to flank the entrance to a gallery, each still partially rolled at the bottom (a reminder that there’s more to come in this story). On one, drawn way above eye height, is a depiction of a terracotta bust of the Demeter of Olbia, an object previously housed in the museum; on the other, a hand is shown holding a spear, a detail from the mosaics of St Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery in Kyiv. The original building was demolished by the Soviet authorities during the 1930s, but not before its mosaics were prised off the walls and spirited away to the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, among other places. Kadan’s rolls deepen into monochromes of pitch-black charcoal towards the middle and bottom, leaving a dark lacuna in the viewer’s line of sight, suggestive of absence or cultural erasure.

This blackness is carried over in a series of drawings, made in the last few months, of stone cherubs and funerary statuary (including Sirens of the mythological sort) that aren’t included in the museum show, but which the artist will send to New York for an art fair. In each, the composition is interrupted by pitch-black egg-shaped voids. When I ask him about these elements, Kadan chooses his words carefully, cocking his head occasionally to see how they land. He is proudly Ukrainian, he says, and has nothing but fury towards Russia, but says Ukraine needs to look inward, too, to tell this chapter of its violent history. “Societies which are at war develop things like self-censorship, there’s the constant violation of human rights, we live in a way that human life is not seen as valuable,” Kadan says, referring also to Ukraine’s forced-conscription polices. These works, titled The Siren of Kyiv (2025), contain “empty speech balloons, but the balloons are also egg-shaped, and I want them to suggest something about the future and what is to be born anew”.

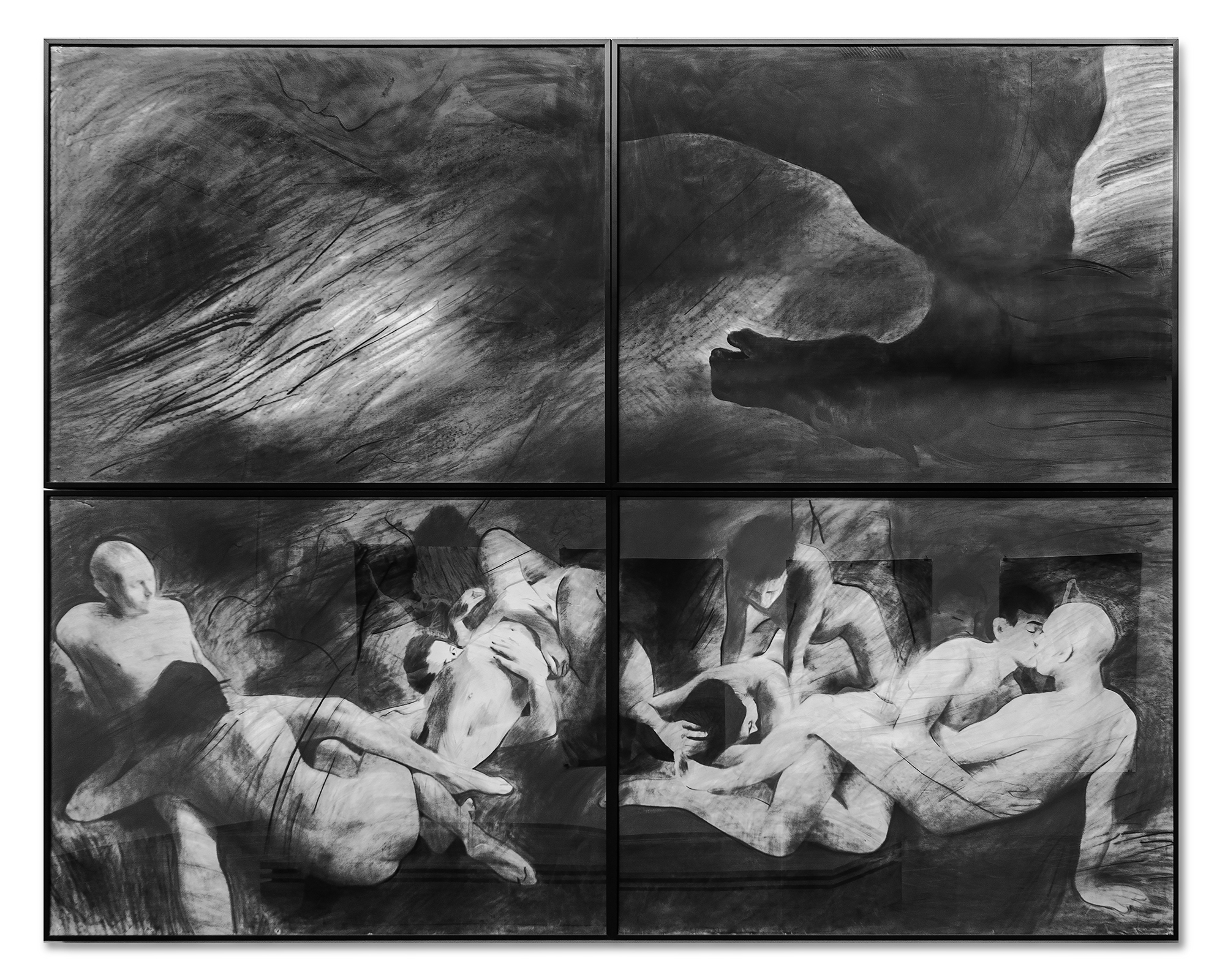

Kadan says, however, that war has also precipitated relative “moments of freedom”: despite the prevailing monochrome of Kadan’s work, nothing is black-and-white in Ukraine’s trauma. “I found that the museum was much more open and ready for risk and ready to show some works of mine which wouldn’t have been shown by a Ukrainian state-run institution before.” Works such as Schekavytsia Mountain (2025), which relates to a Ukrainian meme about an orgy to be organised at a beauty spot overlooking the city in the event of a Russian nuclear strike. The vast drawing, quartered into four frames, depicts an entanglement of naked bodies, while, just discernible, a black horse rears up in the black-clouded background. Kadan says he wanted it to have the energy of a patriotic romantic painting. “Something which is absent in Ukrainian art-history because we didn’t have a nation-state. Western nations had a period of romanticism, romantic nationalism. We didn’t have our Eugène Delacroix and Liberty Leading the People. [1830].” The empty museum was open to showing such an explicit scene, Kadan believes, because “This is an image of freedom among those who have nothing to lose. An extreme moment in a moment of big risk. You can get a lesson from such freedom, but it doesn’t last forever.”

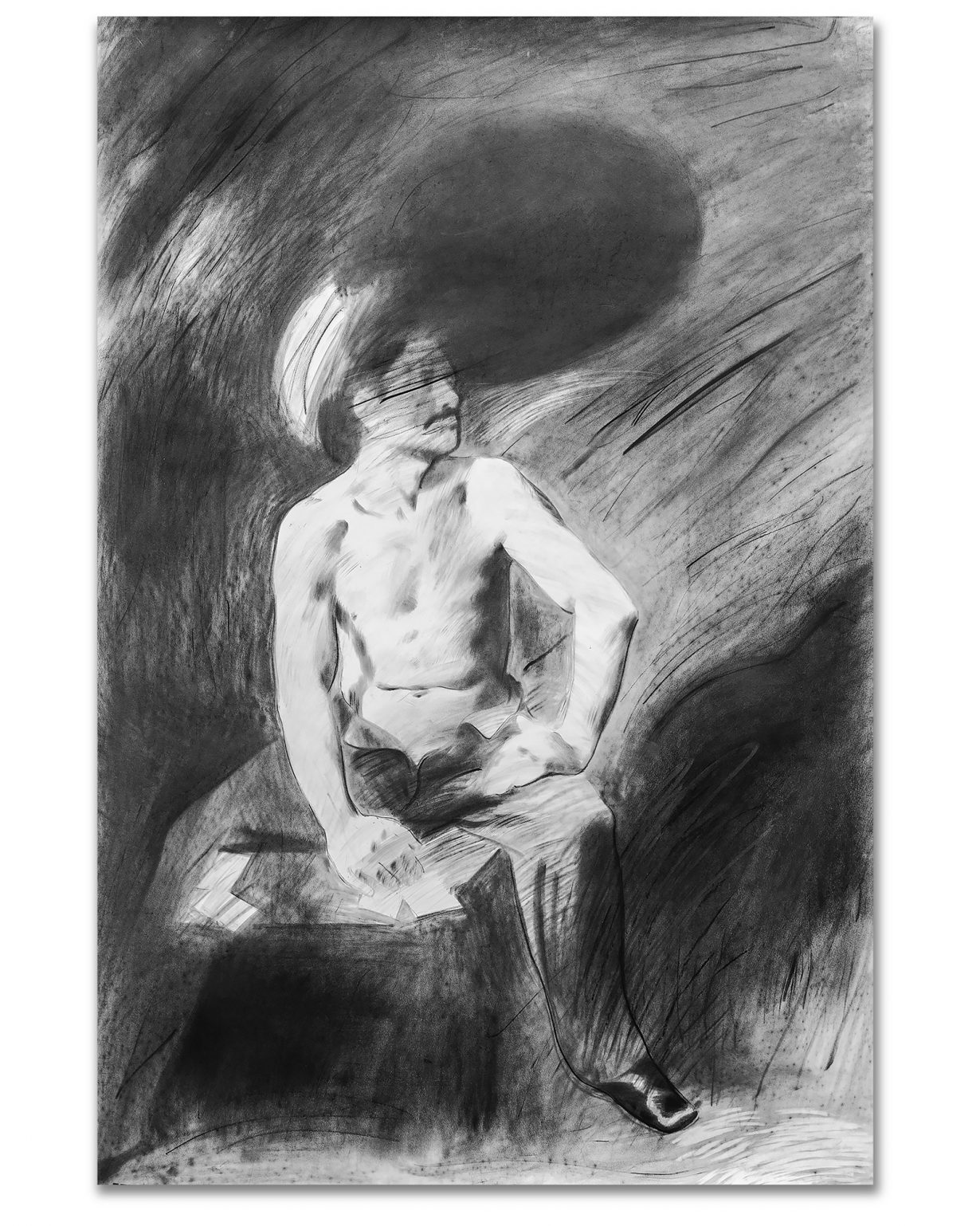

Equally erotic is Sinnerman (2025), a series based on Parable of Prodigal Son (1856–57), a set of drawings by Taras Shevchenko, the Ukrainian poet and artist (whose statue stands a walk away from the café, his head peeping out from the boards and sandbags that are currently protecting all the city’s public monuments). “Shevchenko is considered to be the father of the nation, but this image of a patriarchal figure overly simplifies his life and work,” Kadan says. The appropriated self-portrait is intensely homoerotic: Shevchenko is shown writing on sheets of paper, topless with the flies of his trousers suggestively undone. Kadan says the history of the original Shevchenko sketches have a bearing on Ukraine’s current reality. “These are the drawings he made after being drafted into the Russian army as a punishment for his poems and political activity. Taras Shevchenko: he is our Caravaggio, our Peter Hujar. He shouldn’t just be part of the history of Ukrainian national struggle, but of a queer history of Ukraine. For many years it was a blasphemy to speak of Shevchenko in this way.” Next to Sinnerman Kadan will hang A (2025), a portrait based on a selfie by his friend Artur Snitkus, an artist and musician who was forcibly drafted into the Ukrainian army and killed on the front line. “He was an artist, a queer person, he was a person with a great talent who challenged gender norms… For me the Sinnerman is Taras Shevchenko, but it is Artur Snitkus too.” This is the dilemma Kadan’s work seems to present: how to be a wartime artist? Kadan says he is happy for his work to be framed by his nationality, if it helps the war effort, but he also clearly sees the role of the artist to be something of a regulator, a guardian to those moments of freedom.

Ōshima Seishōen Sanatorium and Japan’s 12 other state sanatoriums opened at the beginning of the last century in order to make disappear the ‘national disgrace’ of 30,359 people with leprosy, most of whom, for reasons relating to their disability, had turned to vagrancy or begging. The government then zealously pursued what was dubbed the muraiken undō policy of strict segregation for the entire patient population. It was wrapped up in both a modernisation project and a nationalistic desire for a ‘strong’ and ‘able’ militarised society: the sick must be cleansed for the state to survive. Roughly translated as the ‘No Leprosy Patients in Our Prefecture Movement’, muraiken undō was a massive government-funded health campaign that instilled shame on the diseased and swept communities of any patients living among them, corralling anyone suspected of having leprosy and transporting them to remote hospitals from which they had no prospect of ever leaving. The patients were given forced sterilisations and abortions, illegal beyond the walls. Kadan recognised an overlap between present-day Ukraine, and Japan’s biopolitical past. “Even before the war I worked with zones of social vulnerability,” he says. “The history of Ōshima and the residents’ experience felt familiar. There is mass violence and its normalisation through law and through tradition.”

After the Japanese segregation law was repealed in 1996, a group of patients sued the government and won damages. With the money, patients from each of the country’s sanatoriums built small museums to preserve the memory of what happened to their communities. Ōshima’s museum and library is filled with archive photographs and objects showing the life they made there, despite everything: black-and-white pictures of a theatrical group active since 1910, objects from the shrine established and sports clubs founded. When Kadan visited in preparation for the Setouchi Triennale, he was immediately struck by the wooden prosthetic limbs on show, constructed by the patients themselves (untreated leprosy commonly causes a loss of sensitivity and secondary infection, leading to possible permanent damage to extremities). He cast one of the hands and one of the feet, each attached to tall thin armatures that will cross, creating something reminiscent of a Giacometti walking figure. These will be scaled up and cast in bronze and, with the title The Branch and the Stick (A Monument of Support) (2025), become a permanent addition to the site. “My proposal was related to the practices of mutual support. I was especially interested in the history of community here, of how people would support each other and form internal networks,” he says. “In this place, which was something between a sanatorium and a concentration camp, there were poetry clubs, sports clubs. Amid this annihilation they still made something like a human life. There is a place for joy and pleasure under missile strikes too: you’ve witnessed it, Kyiv looks like a normal city. People are going out, meeting friends, and then sometimes missiles hit the buildings and people die.”

During my own research, I had asked the residents of the various Japanese sanatoriums why they felt so keen to establish the onsite museums. They reminded me that they were denied the right to have children, that for many their past was also swept away, disowned by families that feared being persecuted by association. The former patients needed a place that would embody their memories: a battle against a second erasure. It made me recall a line Walter Benjamin wrote, one I kept turning back to while writing my book, Outcast: A History of Leprosy, Humanity and the Modern World (2025). ‘To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it “the way it really was”’, but an understanding of history is about seizing ‘hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger’. Professional curators and historians are beginning to replace the patient volunteers who founded the institutions. The curators told me they struggled with the partisan verve with which the exhibits were organised – to frame the government and medical authorities as an uncompromising enemy – anathema to their academic training. The patients’ mode of organisation, however, feels akin to Kadan’s own Benjaminian reading of historiography.

I ask Kadan what he thinks a Ukrainian national museum will look like after the war. “After the war? Who said the war will end? Ukraine will be at war for many, many years, and even after some formal peace agreement is signed, society will still be mentally at war… I can hardly imagine a real postwar situation. Like the patients in Ōshima, all we can do is try to build micro utopias inside this reality.”

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.