Myanm/art director Nathalie Johnston looks at the development of the country’s art scene after nearly five decades of dictatorship

What happens when a nation of just under 55 million people emerges from almost five decades of harsh military dictatorship? When, all of a sudden, those millions gain access to communication that is both instantaneous and uncensored (where once it was neither)? When that access to information opens windows not only into the lives of your neighbours, but also to your politicians, your civil servants and even your children? And how do artists respond to such changes, to this rapid and radical encounter with a type of modernity? How do they respond to this transition and find a voice where they had none before?

In Myanmar the intellectual space created by the first free and fair elections in 2015 (the first in which the results were allowed to stand since the military took power in 1962) has allowed artists to explore public expression with few restrictions. In fact, their biggest problem is often a lack of public space – parks, squares and art institutions, etc. As a result, the present flowering of artistic expression occurs in private galleries, online or in the street. And yet these forms of expression are not a part of some newborn discourse; the works of art being produced probe the many historical layers barely hidden beneath the surface of the times in which we are living. These layers include legacies of colonialism, military dictatorship, the quest for freedom and democracy, the problematic relations between the Burmese Buddhist majority and the numerous ethnic minorities in the country. And Yangon’s con- temporary art scene is where they collide.

In 2015, for example, artist Emily Phyo performed her own version of a census, photographing a different person every day for 365 days. She recorded their names, professions and ages.

That same year, Chaw Ei Thein’s Camouflage Series reflected upon the violence done in the name of Buddhism by painting camouflage colours on sandstone statues of Buddha.

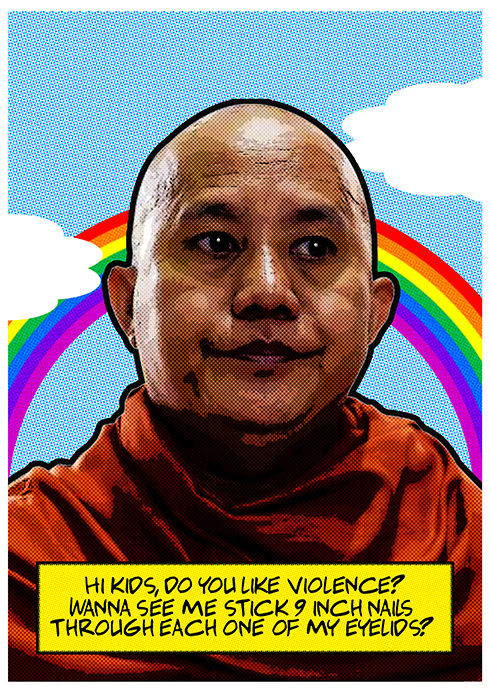

In 2016 Bart Was Not Here – a twenty-something Burmese Muslim graffiti artist from Yangon – designed an uncomfortable series of prints picturing the infamous faces of Myanmar’s political figures past and present, such as military dictator Ne Win and the Buddhist extremist monk U Wirathu. In 2019 Kaung Su created a series of paintings titled Genocide, which referred to the ethnic communities of the country and their susceptibility to climate change with abstract storms of colour on paper. The same year artist Htein Lin exhibited Recently Departed, a lifesize replica of a burned and charred house made of wood and rattan, referring to the burned-out villages of Rohingya and Rakhine people in Myanmar, and installed it in the most important colonial building in downtown Yangon – The Secretariat.

Prior to 2015, international discussion concerning Myanmar was all about the fight for democracy. Now, it is almost exclusively around the genocide of the Rohingya population, who suffer not only from violence and discrimination but an almost total lack of visibility within civil society. Important as these two issues are, to those living in the country, Myanmar’s issues expand far beyond these two poles. Since 1948, Myanmar has been in a constant state of civil war between ethnic armed groups and the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s official armed forces. Poverty, natural disaster, gender inequality, religious extremism and climate change are just some of the regular traumatic experiences of those living in the country. And by opening up discussion about such issues, Myanmar’s contemporary art scene is playing an important role, and one deserving of more attention than it currently receives. And, of course, I have a vested interest in that.

In January 2020 Myanm/art, where I work, hosted Richie Htet’s first solo exhibition. In an interview that accompanied the exhibition, Htet described being taunted as a young boy on account of his dark skin. His classmates would use common racial slurs such as kala, a term historically used to refer to people from India, but now referring to skin colour. And the slurs have followed him into adult life. But now they relate to his being queer. In an act of defiance, he titled his exhibition A Chauk, a derogatory term for queer people in the Burmese language. In a series of paintings and drawings representing queer bodies, he both shocked and impressed the audiences. This was the first-ever public exhibition in Yangon featuring multiple nude males and male genitalia in artwork. Htet’s might not seem like revelatory work in major cities today, where art is an integrated conversation piece.

Myanmar was a closed country for many decades, not only to international visitors but also to its citizens. Poverty did not allow them to travel, and neither did the infrastructure. All schools and universities were administered under the direction of the military, and Buddhism reigned as the national religion. Such factors produce a society that tends to be traditional, conservative and slow to accept change. Even within the arts, audience members are sceptical of experimentation or alternative artforms that do not hold with tradition. But many visitors to Htet’s exhibition asked how it was even possible to show such work in the country’s largest city without censorship. Here, each exhibition and every new risk taken is a step towards understanding what a post-dictatorship society can be.

Nathalie Johnson is director of Myanm/art, Yangon

First published in the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia